Against the farce of quiet luxury: The problem with dressing like a rich person from ‘Succession’

Unbelievably, amid inflation and scarcity during the global pandemic, as the wealthy have increased their fortunes while the poor have become much poorer, the world wants to emulate their style

When the second season of Succession premiered in 2019, Donald Trump was still president of the United States and the Covid-19 pandemic had not yet taken place. At the time, a column in The Guardian pondered the show’s success, that is, our obsession with the super-rich people portrayed in it. The piece concluded that we are fascinated by seeing how these people also suffer (albeit for other, less dramatic reasons) and ended by noting that “I’m not sure we’re going to have a Succession line of clothes in Banana Republic any time soon…

The old-fashioned has an inherent sexiness, and Mad Men revived that, but the cable knit sweater is a little bit of a harder sell.” Four years later, Trump has left office, the pandemic is on its last legs and internet searches for Succession’s fashion and for what is referred to as quiet luxury—which describes that 1% of the population somewhat heterogeneously—have increased tenfold. We don’t know if Banana Republic or any affordable fashion brand will launch a line inspired by the Roy family. But if they did, it would be a contradiction, because if anything defines quiet luxury, it’s not the aesthetics but rather the material aspect. Paying €2,000 for a camel hair sweater from The Row or €500 for a basic Brunello Cuccinelli T-shirt, made in an Italian village by a community of humanist seamstresses (really). The latter is Mark Zuckerberg’s favorite shirt; it makes him seem unconcerned about his own attire because he has more important things to think about but is still powerful enough to pay a small fortune for the most insignificant object in existence and have dozens of the same model in his closet, to boot.

When discussing fashion, there is talk of individual expression, of a visual reflection of the present, even of political vindication. All that is true but underneath it all is the idea of aspiration as the main driver of consumer desire: aspiring to look like the celebrity one admires, to participate—if only through one’s wardrobe—in the lifestyle suggested by this or that brand, or simply to be seen as someone of equal or superior social status as one’s own.

But it is one thing to want luxury, of whatever kind, and quite another to emulate quiet luxury. There is nothing attractive about it except excessive spending, sheathed in arguments as disparate as they are empty. As Vogue defined it, quiet luxury is " less austere than minimalism but more polished than ‘normcore.’” It does not imply the former’s rigorous, almost monastic aesthetic, but its only difference from the latter is that it is made from silk, cashmere or Egyptian cotton. Quiet luxury is characterized by paying what 99% of the population can’t afford and justifying the expense with scarce and exquisite materials. “In the early years, there were women who would run to Barney’s and buy ten identical black sweaters at a thousand dollars each. For them, it was like going to Uniqlo,” the former fashion director of the New York department store says of the history of The Row. That’s the Olsen sisters’ (unprofitable) brand, which epitomizes the idea of quiet luxury: Obscenely expensive, pretentiously basic garments that support their price point based on the idea of extreme quality and precise cut. As if that weren’t enough, the brand has successfully exported the idea of looking carefree and even raggedy in expensive clothes (as the Olsen twins themselves do in their outfits).

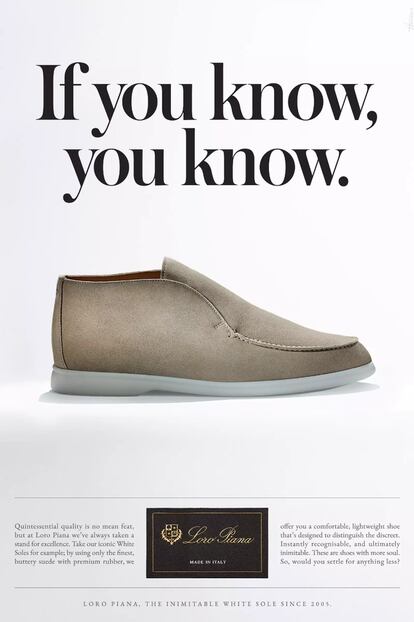

Because it is different, quiet luxury is sold as another super-rich secret society: only they know why it is necessary to spend €5000 on a gray blazer and only they can recognize such quiet luxury in a crowd. In this fiction, the main plot is a billionaire winking at his fellow billionaire when he sees him wearing a gray Cuccinelli sweater that nobody else recognizes. The same goes for the (real) advertising campaign of Loro Piana loafers, one of this trend’s beloved brands. One of the world’s most expensive brands, its slogan is simply, “if you know, you know.” In short, the trend bases the notion of good taste, a cultural construct, on the idea that the powerful are those who create it and, even worse, that they are the only ones who know how to appreciate it.

Of course, the concept of quiet luxury is not new. There are several market studies from as far back as two decades ago that categorize different types of luxury buyers: the poseur (the classic wannabe who aspires to social status), the parvenu (the classic nouveau riche) and the patrician born with a silver spoon in his/her mouth, who despises logos and trends. This rhetoric is perverse in and of itself, but it is deeply rooted in society: the logo, with which brands have made so much money, is tacky, as tacky as getting rich instead of being born rich. Only old money, with its contemptuous look, really knows what true luxury is, that which, curiously, only 1% of the population can afford. But if more than 1% could save up to afford to buy €600 white T-shirts, that 1% would invent another code and also disguise it as knowledge, longevity and good taste.

you don't actually love "quiet luxury." you're in love with the idea of inherited wealth, spacious uncluttered homes, and enough free time to pursue your hobbies pic.twitter.com/OwSn6wWxVP

— derek guy (@dieworkwear) April 16, 2023

It is hard to believe that amid inflation and scarcity during the global Covid-19 pandemic, through which the very wealthy have become much richer while the poor have gotten much poorer, the world wants to emulate the style of quiet luxury: a fictionalized rich person costume, fashion without a concrete style, a masculinized style (in which women still have to dress in sober suits because power is a man’s thing and adornment is very unserious). But above all, it’s a style that is associated with a minority that oppresses, enriches itself through others’ needs, and inhabits a microcosm that is far removed from the daily reality that it sometimes scorns. That’s the reality to which the Murdochs (who supposedly inspired Succession), Bezos, Zuckerberg and, yes, Donald Trump belong: no wonder the character Shiv, who is (supposedly) going in the other direction, occasionally appears in dresses by Chiara Boni, the brand worn by Fox anchors and other women who participated in his regime.

While the hashtag #oldmoney (which is not necessarily the same as quiet luxury but shares the same roots) has been trending among young people on TikTok videos for two years, social media and some lifestyle media have moved into the incredible contradiction of seeking to copy very rich people’s style at affordable prices. It’s not emulating a trend or an aesthetic; it’s emulating an attitude that should, at the very least, be prosecuted. It makes sense that next fall’s runways have been filled with basic garments (they’re very expensive, but largely without reaching the obscene prices that the quiet luxury brands charge, nor are they as ordinary); at times of impending crisis, you have to trust the super-rich. But it makes no sense to buy the discourse that sustains them, which speaks of longevity or, in financial terms, an investment or safe value. Does anyone know a person with a €3000 coat who only wears that same coat season after season?

“You don’t actually love ‘quiet luxury.’ You’re in love with the idea of inherited wealth, spacious uncluttered homes, and enough free time to pursue your hobbies,” fashion editor Derek Guy wrote a few days ago in a tweet that went viral but with which many disagreed. Turning the fiction of wealthy clothing into a trend obscures everything that is pernicious about it; it implies believing in the utopia of the social ladder and even denies fashion itself.

Because fashion was not invented by the rich; it was invented by the poor. Without the Industrial Revolution, that is, without sewing machines, there would be no fashion, because the non-privileged classes could not have had cheap access to the aesthetics about which the privileged boasted (before the French Revolution it was not even legal to emulate the aristocracy’s attire). It is this game of cat and mouse—that is, between the popular class that emulates the wealthy, and the upper class that dissociates itself from whatever is emulated (as Georg Simmel described so well in his 1905 text The Philosophy of Fashion), which gave rise to fashion as a social system (and an object of consumption). But that is precisely why resorting to the myth of the quiet luxury of a discreet upper class that despises a visually noisy popular class doesn’t appeal to fashion (to that extent, the tables have turned). There is nothing wrong with using it to express oneself, aspire to something or even play at being someone else. But it is wrong to turn the unconsumable into consumption because it is both economically and ideologically inaccessible.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.