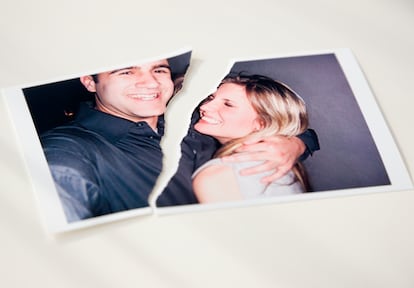

How the stress of trying to have children can end a couple’s relationship

Fertility treatments don’t just involve a considerable biological and economic cost, there’s also the anguish and frustration in the case of them not bearing fruit. Avoiding the instrumentalization of sex and communication are key for the survival of a relationship

The apocalyptic Malthusian theory that stated that population was destined to grow in geometric proportions, while food production grows arithmetically, is beginning to deflate. The future looks more like the one outlined in The Handmaid’s Tale series, in which fertilizing children becomes biological acrobatics with a triple somersault. What Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) did not count on in his prophecies was environmental pollution, food toxicity (ours is full of pesticides, in the intent of ending world hunger) and endocrine disruptors (particularly those present in cosmetics and cleaning products); the main causes of semen’s plummeting quality in recent decades.

“In the ‘90s, the percentage of good spermatozoids (well-shaped and with good mobility) in the masculine population was at 30%; in 2000 it dropped to 14% and in 2010 it was located at 4%. Today, 60% of couples don’t even reach this threshold. It’s also thought that this pollution could be related to abortions and the difficulty of implantation in women,” says gynecologist Antonio Gosálvez, expert in assisted reproduction and emotional communication and director of the Assisted Reproduction Unit of the University Hospital Quirónsalud in Madrid. So pronounced is the issue that, as the expert points out, one out of every five children born in Spain is the result of assisted reproduction. And he predicts that this number will increase.

If in a not-too-distant past unwanted pregnancies were a common problem, these days many conflicts arise over wanting children and not being able to have them. Turning to assisted reproduction not only entails considerable economic cost (from €1,000 for an artificial insemination to €6,000 for one cycle of egg donation); one must also tally up the stress and frustration that can result in the case that it doesn’t bear fruit. It’s an ordeal that not all couples survive.

For Toni (53 years old, Barcelona) it meant the end of his relationship. It all began when he was 37 years old and his female partner, 38. His sperm wasn’t doing the trick, so the first phase of the fertility treatment consisted of providing her with medical treatment to make her more receptive and increase the possibilities of success. Toni remembers the sex from this time as being “stressful and artificial”: “We had to do it at a predetermined moment and then wait for the next most favorable date. Any hint of spontaneity was contraindicated.” When that didn’t work, plan B was artificial insemination with a donor. After three unsuccessful attempts, the final option was foreign adoption, since facilitating one in Spain was almost impossible. “The problem with that situation is that you fall into an unending circle, and if you want to press stop, you have become the bad guy, the egotist, the one who isn’t taking into account the other’s feelings,” says the Catalan economist and lawyer. “I was the one who put an end to the relationship, because my partner wanted to adopt three Mexican children (they were siblings and she didn’t want to separate them). But I wasn’t quite clear on how we were going to bring these three people, all of a sudden, into the family; because in addition, our financial situation was not exactly buoyant in those days.”

Araceli Álvarez is a psychologist, sexologist, couples therapist and family mediator. She works in Artea and Aide, two psychology and sexology offices in Sevilla, and has provided psychological support in various family planning clinics, so she has in-depth knowledge of the seismic shock experienced by many couples seeking offspring. “The maximum friction points are found in sexuality and communication,” she underlines. “In the sexual sphere, an abrupt change is experienced. Something that, at first, can be pleasurable becomes a routine that can cause discomfort. It becomes instrumentalized,” she says.

If the foundation of the couple’s relationship is primarily based in sex, it may stumble and fall, due to what Gosálvez calls “military sex” that, paradoxically, does not result in the desired effects. Many women can feel empty, incapable of conceiving; while some men may end up with a “stud complex,” thinking that their partner no longer wants them for them, but rather their energetic little cells needed to fertilize their ovule. “The frustration of not being able to have children can be lived differently depending on one’s sex, although there are always exceptions,” says the gynecologist. “Motherhood is somewhat more instinctive, whereas fatherhood is a more rational desire. Because of this, the woman can live everything much more intensely; the anxiety of having descendants or the frustration when treatments fail. On the other hand, the hormone cocktail of fertility treatments can only enhance these mental states.”

Gender stereotypes, which have recently gotten such bad press, make themselves at home in these situations, and are reinforced by many couples during the long process of assisted reproduction. “Unfortunately, that’s how it is,” says Álvarez. “I’ve seen how in some assisted reproduction clinics they advise the men to stay strong, be the weight-bearing pillar for the couple’s morale; as if they don’t have any feelings or emotions. But in many cases, he takes on the role unconsciously, while she’s the one who suffers most, who cries and complains. Some men also feel very guilty if the problem in conception lies in them. I remember the case of one patient who came in crying because his friends were making fun of him, asking ‘if his gun had jammed.’”

What Gosálvez most commonly sees in his office is a man will become the mirror, the loudspeaker of the woman’s emotions and demands. “It’s a very delicate matter and must be treated with a lot of care. In our clinic all of our professionals offer emotional support throughout the entire process, and we have a psychologist available if necessary. I always say that I’m not treating two people, but rather three patients: the man, the woman and the couple. Because in addition, when they decide to go to a fertility clinic, most women have already self-diagnosed before they get there, and have tried a series of recipes that they find on the Internet or on fertility message boards, where people share all kinds of myths, like that one about propping your legs up after sex to get pregnant.”

The subject of communication that Álvarez mentions is another issue that must be navigated in times of infertility. In fact, she advises that in order to embark on this mission, it’s essential that the couple gets along well and has good communication skills. If not, “there is a high probability that they will break up.” If the idea that children bring parents together is false, believing that fertility treatments will iron out marital problems is a fantasy. “Even the most well-suited couples find themselves immersed in fights, accusations, second thoughts about decisions that they’ve made and the opinions of family and relatives, who often aren’t doing anything but adding fuel to the fire. I don’t even want to imagine what might happen if the couple begins the process with poor communication skills!” says the psychologist.

With that said, another question comes to mind: Should we tell close relations about the process, or is it better to keep quiet? In Álvarez’s opinion, it depends on the situation: “If they’re the type to listen respectfully and provide support, yes. If not, no. In these moments, one has to weigh comments so as not to hurt people’s sensibilities, particularly because sometimes, well-intentioned advice can be interpreted in a negative way. In many cases, rather than talking, the best technique is to ask questions, listen, and be there for the person.”

But perhaps the most bitter pill when it comes to assisted reproduction are its repeated failures. “Failure is intrinsic to the search,” says Gosálvez, “but frustration can be prevented with accurate information, with a neutral focus that acknowledges the possibilities of success and failure. Nowadays there are fertility clinics that advertise themselves with guarantees of success or your money back. That doesn’t seem ethical to me, because it generates false expectations. It’s not so easy to get pregnant. In fact, success rates are: for artificial insemination (with a semen donor), 30%; in vitro fertilization, 50%; and with an egg donor, 65%. You’ve also got to turn down patients who have very a very low chance of fertilization or when there’s a high risk for the child (due to age or other circumstances). We do it all the time.” Another piece of advice from professionals to couples in search of offspring is to “know when to stop; whether you take it up again at a later date or give up entirely, before winding up damaged emotionally, physically or economically.”

Maribel (62 years old, Madrid) knew when to hit the brakes. “I got married at 39 and had never felt called to motherhood. It was my partner who wanted to have kids, so I started fertility treatment, which didn’t sit well with me,” she remembers.” It left me worn-out, so we decided to pause for awhile. I think that took away our anxiety and stress around having kids, and put everything in perspective. When we gave it one last chance, without a lot of expectations, we got lucky and today we have a wonderful daughter.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.