From Havana to Damascus: The story of rebel commander Bachar Alkaderi

The Syrian surgeon, trained in Cuba, warns that, after the overthrow of the Assad regime, ‘the revolution must be protected from its own children’

Among the rebels who, on December 8, entered Damascus and put an end to almost 14 years of conflict and the Assad family regime — one of the cruellest and longest-lasting in the Middle East — was one who spoke Spanish with a slight Caribbean accent. Dr. Bachar Alkaderi, a graduate of the University of Medical Sciences of Havana, specializing in general and thoracic surgery, became, through the twists of fate and history, a revolutionary commander.

“When I entered Damascus, I felt like I was returning from a very long exile. I hadn’t seen it for more than 13 years,” he explains via video conference from Deraa, the southern Syrian city he comes from. A year after overthrowing the regime, however, he is more cautious than euphoric: “More than from its enemies, the revolution must be protected from its own children.”

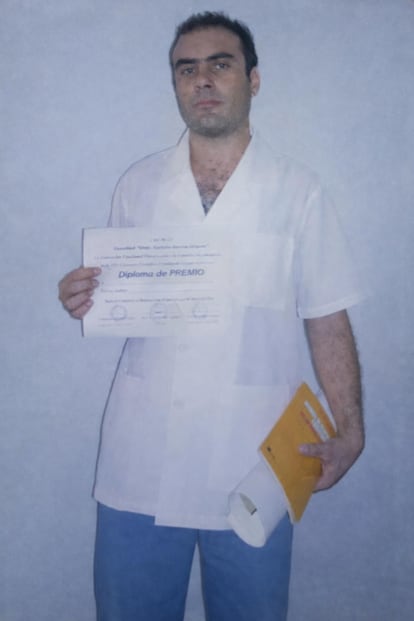

Alkaderi’s training began far from home, in Cuba, where he arrived in 1997 — at the tail end of the hardship known as the Special Period — to study medicine. His specialty diploma notes that he graduated at the top of his class thanks to his excellent results, and it is dated November 2009, marked as the “Year of the 50th Anniversary of the Triumph of the Revolution.”

Alkaderi is one of the hundreds of Syrians who trained in Cuba through a program that began during the Cold War and continued even throughout Syria’s civil war. The initiative reflected the close relationship between two governments that portrayed themselves as allies against U.S. imperialism. However, the last thing Damascus expected was that some of the young people it sent to study in a friendly country would turn against it.

“In Cuba, I learned the revolutionary spirit,” Alkaderi says with a smile. “My experience during my medical and surgical studies was profoundly beautiful. Cuba is a true school of patience and dignity. I saw a people poor in resources, but immensely rich in pride; a people capable of transforming the [U.S.] blockade into science and production.”

What Alkaderi learned as a doctor in Cuba became essential almost immediately after he returned to Syria. By late 2011, peaceful protests against Bashar al‑Assad had escalated into an armed conflict in response to government repression. Working in extremely precarious conditions — often without enough medicine, anesthesia, or proper equipment — he performed hundreds of complex surgeries on victims of Russian airstrikes and Syrian and Iranian shelling.

“I joined the Syrian revolution the moment I understood that the Syrian people were living in a vast prison and their voices were being silenced,” he says. “The country was being run like a private estate for the president, his family, and his generals. The army committed massacres at every peaceful demonstration. So my decision wasn’t ideological, but ethical. It was the feeling that to remain silent was to betray.”

For many years, most leftist Latin American governments, beginning with Cuba, embraced the narrative promoted by Syria and other authoritarian regimes that the Arab uprisings were not genuine popular movements but Western‑backed conspiracies. Syrian progressive intellectuals such as Yassin al‑Haj Saleh condemned this stance as a betrayal. “The most horrifying thing is that they haven’t just killed us, but they kill us and insult us,” the Syrian writer told EL PAÍS in a 2017 interview.

“The revolution isn’t a picture to hang on the wall, it’s a way of life,” argues Alkaderi. For him, the Syrian uprising has a strong element of “national liberation” against a regime he accuses of having “sold the country to the foreign occupier [Russia and Iran] and to transnational militias [Hezbollah, Iraqi and Afghan Shiite militias].” “During our revolution, I learned that human beings can stand tall, even when the whole world is upon them,” he adds.

As the conflict progressed, he went from stitching up bodies in operating rooms to commanding fighters in the battles of Daraa. In 2018, after a Moscow‑brokered deal, he was evacuated to Azaz in northern Syria. From there, last year, he coordinated rebel forces in the southern provinces with the offensive launched from the north. “The coordination operated under a principle of ‘disciplined decentralization.’ Each area had its own field command and was based on guerrilla warfare strategy, for which the southern fighters were trained,” he explains. However, the regime collapsed much faster than they expected: “They suffered a moral collapse and abandoned their positions.”

“A year later, I can say that we won the battle, but the road to a country that resembles the dreams of our martyrs is still long,” he says. Like many Syrians, he believes that the indirect elections held under the leadership of the interim president, the Salafist Ahmed al-Shara, and the constitutional declaration of transition, which concentrates power in the executive branch, “are not sufficiently representative” of the Syrian people and their diverse segments.

He lays out what he sees as the priorities for the revolution’s second year: “We must give the people an authentic voice, not a decorative one; establish genuine transitional justice; build institutions that function based on competence, not favoritism; and dismantle the old networks of corruption that are trying to return under new names.”

As for himself, he has put down his rifle and returned to practicing medicine in a hospital in his province.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.