Disappearances, the biggest challenge in Claudia Sheinbaum’s security strategy

Analysts, academics, and security experts are divided on how the number of missing persons in Mexico should be measured, while the government compiles a new registry

On Thursday, January 8, during President Claudia Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, the Mexican government touted a historic reduction in nearly all crime categories in the country. In terms of homicides, 2025 saw the fewest victims in a decade, and there were also decreases of between 15% and 20% in femicides and violent robberies. “This is the result of a security strategy that is yielding results,” declared Sheinbaum, accompanied by her Security Cabinet. And — as is the case every month when the Mexican government boasts about these figures — some civil society organizations and groups of mothers searching for their missing children asked: Why isn’t there any talk about the disappeared?

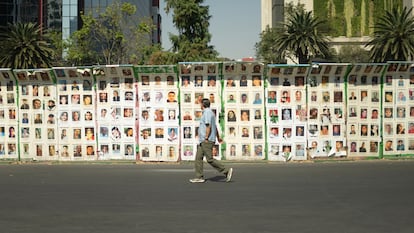

According to the National Registry of Missing and Unlocated Persons of the Ministry of the Interior, 14,072 people were reported missing and unlocated during Sheinbaum’s first year in office. This represents a 20% increase over the 10,924 reported the previous year and more than double the 7,802 registered in 2019, the first year of the presidency of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Sheinbaum’s mentor. Furthermore, 2025 was a particularly horrific year for those looking for their missing loved ones, with seven murders and four disappearances among the coalitions of searchers themselves. Analysts, academics, and security experts are divided on whether this figure, along with other crimes, may be masking murders or if it actually represents a different phenomenon that should be considered separately.

“Mexico is one of the countries in the world that best knows how to count homicides, but this is not the case with the crime of disappearance,” says academic Carlos Pérez Ricart. “The missing persons registries in Mexico are designed to search for people, regardless of whether there are duplicates or triplicates, but they are not designed to measure, so when they are compared with homicide registries, it’s like comparing apples and oranges,” he argues.

The researcher from the Center for Economic Research and Teaching (CIDE) explains that, as reporting a disappearance has become easier in many states, this has led to an increase in the number of missing persons reports and, consequently, in the total number of disappearances. “But a missing person report is not necessarily a missing person, since these can encompass various situations such as disappearances due to criminal activity, people who went to the United States, people who don’t want to be found... some of which are related to enforced disappearance and others not,” he explains.

On the diametrically opposed side is Armando Vargas, coordinator of the security program at the think tank México Evalúa. “The homicide data reported by the authorities is no longer valid,” he asserts. On the one hand, he maintains, prosecutors and police “lack the capacity and the will to classify them properly.” On the other, organized crime — which sets the rules in some territories — “disables the justice system” and “uses disappearances as a mechanism that goes unnoticed by the public and the state.” Associations of mothers searching for their missing loved ones summarize it in the phrase: “No body, no crime.”

“In this context, certain anomalies in the data are explained, which show that while homicides are decreasing, other phenomena are increasing or remaining the same,” he says. These include femicide, manslaughter, other crimes against life, and missing and disappeared persons. Different data sources are also mixed, such as figures from the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System and those from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography, and they measure non-equivalent periods. “If the same periods and the same sources are compared, the methodologically correct annual reduction is much smaller,” he explains. According to his analysis, if all crimes associated with lethal violence in Mexico are added together and compared, the decrease compared to 2024 was 5%.

Last week, Sheinbaum announced that a new registry for missing persons in Mexico is ready and will be presented shortly, probably in the coming days, at one of her press conferences. “We will provide information on both the registry and the new regulations implemented last year, how they are being carried out, and how we are working with groups representing families of missing persons,” she said. Sources close to the Security Cabinet indicate that the total numbers have been thoroughly analyzed.

The National Registry of Missing and Unlocated Persons, which compiles figures from state prosecutors’ offices and search commissions, currently lists more than 133,000 victims. During López Obrador’s six-year term, during which he made insecurity and disappearances a key political issue in his presidential campaigns, a project called the National Strategy for Generalized Searches was launched. As reports of missing persons increased, efforts were made to determine the “real” number of disappearances. A similar plan will be presented by the president’s office next week.

According to a report by the specialized media outlet Where Do the Disappeared Go?, this strategy was abandoned due to “the falsification of signatures on forms from victims who had supposedly been located and from officials who validated them, the loss of hundreds of questionnaires completed by families of missing persons, and the erasure of names from the official registry without formalizing the process.” The issue was simply allowed to die, disappearing from the public agenda.

Almost two years ago, in March 2024, the federal government issued its last public report on the number of people located through the national search strategy. The figures indicated that over 20,000 people had been located out of a total of 133,000 registered. This process led to the resignation of Karla Quintana as Commissioner for the Search for Missing Persons. Respected by search collectives, she stated at the time that “the intention, very clear and regrettable, is to reduce the number of missing persons, especially under this administration.”

“When you bring up disappearances, government defenders argue that, since the registry isn’t reliable, it’s irresponsible to talk about it,” complains Vargas of México Evalúa. “We do see a reduction in intentional homicides, but also an increase in other phenomena such as disappearances, which in the Mexican context makes sense to use to manipulate data or as criminal strategies.” What Vargas is calling for is a review and discussion of all this data with and by the federal government.

“We must be very careful with the assertion that homicides are decreasing but disappearances are increasing,” Pérez Ricart urges. “Yes, reports have increased, and I am certain that crime has also increased, but we cannot know for sure,” he says. “It doesn’t seem to me to be statistically significant enough to obscure the bigger picture: the 40% reduction in homicides last year. However, the crisis of disappearances is real and of enormous proportions. That is the difficulty in measuring it. The records we have today cannot do so.”

The historic decrease in homicides, an achievement celebrated by the Mexican government, raises suspicions among the more skeptical analysts. “No body, no crime,” some say. “It’s not the central issue,” others reply. While the new national registry is expected to shed light on this dark area, the mothers searching for their missing loved ones continue to ask: Why is there no talk about the disappeared?

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.