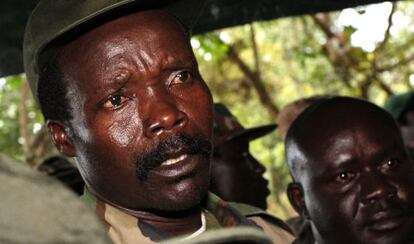

A warlord, a bathtub and a court with its hands tied: The Hague revives the hunt for Joseph Kony

The International Criminal Court continues to hunt for the ruthless Ugandan war criminal, who once escaped US efforts to capture him

Joseph Kony is a religious fanatic — a Christian one. He believed himself to be a prophet whose divine mission included abducting, raping, impregnating teenagers, and mutilating and killing. He carried out this mission from 1987 in Uganda as the leader of an armed group with cult-like tendencies, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), whose hallmark was “using girls as sex slaves,” according to a ruling by the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, which has just reopened the search for him.

The LRA abducted between 40,000 and 80,000 people in Uganda until the mid-2000s. At least 100,000 people were killed, and more than two million were displaced by the violence of this group and its enemy, the Ugandan army, according to the United Nations. Kony would cut off the hands, ears, lips, and noses of his victims and then force them to eat their own body parts.

In 2005, the ICC issued an arrest warrant against him for 39 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Twenty years later, no one has captured him — he is the longest-running fugitive sought by the court — but now The Hague has officially reactivated the search, at a time when few, aside from his victims, still remembered this criminal-turned-ghost.

On September 9 and 10, the court held a hearing to confirm the charges hearing Kony. It was the first time it took place “in the absence of the accused,” notes Ana Manero, professor of Public International Law at Carlos III University in Madrid. This raised a glimmer of hope that the case could set “a precedent” and open the door to something bigger: trying other alleged criminals wanted by the ICC in absentia. such as Russian President Vladimir Putin and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

On November 5, that hope was dashed. The Hague confirmed the charges against Kony, warning that it would not be possible to try him without his presence. The Rome Statute, the ICC’s founding document, prohibits it. “The court has its hands tied,” laments Manero. Nevertheless, the prosecution’s push to try a defendant in absentia has opened a path. “It’s a very cautious step forward,” says the professor, but it does set a small precedent. Not to bring powerful figures like Putin and Netanyahu to justice — they remain beyond the reach of the ICC, which is not backed by a police force —but at least to ensure their crimes are formally acknowledged, their victims receive recognition, and the perpetrators are publicly condemned

Not enough to bring powerful defendants like Putin and Netanyahu to justice — they are beyond the reach of the ICC, as the court has no police force to enforce its rulings — but at least enough to ensure their crimes are formally acknowledged, their victims receive recognition, and the perpetrators are publicly condemned.

An epiphany

Alice Auma, from Uganda, spoke with waterfalls, hippos, and giraffes. Even with stones. Literally. She was the pioneer who laid the foundations for the messianic movement that would later be led by Joseph Kony.

It all began with an epiphany. In January 1985, Auma asked a waterfall on a tributary of the White Nile about the violence ravaging Uganda. By then, she had already adopted the name Alice Lakwena (“messenger”), after the spirit she claimed possessed her: an Italian army captain who had drowned in the Nile at 95 — an improbable age for someone serving in the military.

After hearing the waterfall’s laments about human cruelty, Auma launched a rebellion: the Holy Spirit Movement. Many of its rules were based on the Ten Commandments: “Thou shall not steal,” “Thou shall not kill,” “Love your neighbor as yourself”… Others were suicidal, such as the requirement not to take cover on the battlefield; or cryptic, like the rule forbidding carrying twigs in one’s pockets. One final command raises questions about the men Auma had encountered: “You must have two testicles. No more, no less.”

A year after Auma’s conversation with the waterfall, in January 1986, Ugandan president Tito Okello, of the Acholi ethnic group, was overthrown by what was then called the National Resistance Army. Its leader, who seized power, still leads Uganda today: Yoweri Museveni. The Acholi are the majority in northern Uganda. Auma, like Kony, was Acholi too.

Auma’s militia, the Holy Spirit Movement, grew to 10,000 members but was defeated in 1987 by Museveni’s forces. Many died. The medium then escaped to Kenya by bicycle. The surviving militiamen returned to northern Uganda, where a young man claiming to be the fugitive leader’s cousin took command of the messianic militia and later renamed it. Thus, the LRA was born. Its ideology drew on a mix of Christian precepts, Acholi nationalism, animism and Auma’s batty environmentalism.

That young man was Joseph Kony. He was born around 1961 in Odek, Uganda, and sought to overthrow Museveni and impose a theocracy based on the Ten Commandments. The former altar boy did not hesitate to subject adults and children — between 20,000 and 40,000, according to various sources — to unimaginable tortures in God’s name, abducting them and then turning them into perpetrators of atrocities against other victims. This was what happened to Dominic Ongwen, who was captured and sent to The Hague in 2015, and is serving a 25-year sentence for crimes against humanity.

Ongwen had been a kadogo (Swahili for “small one”): a child soldier. His trial in The Hague revealed the tortures he endured. He was forced, for instance, to skin another child alive to punish an attempted escape. Among these horrors, perhaps the least unbearable was carrying the leader’s belongings through the African jungles — including a bizarre item for a war criminal: his bathtub.

In 2006, months after The Hague issued a warrant for his arrest, Kony fled Uganda. He is believed to have hidden in the border triangle where the Central African Republic, Sudan, and South Sudan meet — or in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The “latest rumors” from years ago placed him in Sudan’s Kafia Kingi region, explains Iván Navarro, a researcher at the Escola de Cultura de Pau at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB).

Uganda, with Washington’s support, even deployed a small force — 1,500 soldiers and about a hundred U.S. advisers — to hunt down the warlord. Their base was in Obo, in eastern Central African Republic, where Dominic Ongwen had defected. In March 2017, those troops were hot on Kony’s trail. But when they reached the camp the fugitive had just abandoned, they only found the bathtub — the same one previously carried on the shoulders of kadogo — in which the warlord liked to bathe, according to The New York Times.

The war declared by the Obama administration against the Ugandan warlord in 2011 thus ended with a bathtub as the only trophy, the closure of the mission in April 2017, and $800 million gone from U.S. coffers.

Jean (a pseudonym), an aid worker who assisted LRA victims in Obo, recalls how many locals were suspicious of the presence of muscular U.S. veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. Their presence seemed so disproportionate for pursuing a fading warlord that people began to believe they must have another objective — such as “looking for oil.” Kony was already over 50 — an old man by local standards — and his militia had become a “hunger guerrilla,” a few dozen gaunt fighters who looted simply to eat, though they still abducted children.

Navarro argues that the Kony case has given the Ugandan regime “a blank check and the support of a large number of international donors, especially the United States.” This is despite the fact that the ICC has not included in its case the terrible “war crimes also committed” by the Museveni regime.

The viral video

A chance event also strengthened Museveni by turning Kony into a pop-culture figure. In 2004, several young Americans from an evangelical sect — the Emerging Church — visited Uganda. Shocked by the horrors of the LRA, they founded an NGO in San Diego, California called Invisible Children.

In 2012, the NGO released a video titled Kony 2012, which showed children abducted by the militia. The film placed its founder in Uganda, even though by that point he had already been on the run from the country for six years. On March 6 of that year, host Oprah Winfrey shared the video on her social media account, and it received 120 million views in just five days. Singers Rihanna and Justin Bieber also tweeted about Kony. Invisible Children raised $12 million with that documentary, which delved into the past. Today, the United States continues to offer a $5 million reward for Joseph Kony. And the ICC still hopes to bring him to trial.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.