Venezuelans deported to Bukele’s mega-prison reveal torture and other abuses: ‘They said we would only leave in a black bag’

Human Rights Watch documented the mistreatment of 252 migrants that the Trump administration sent to El Salvador, and who were later released and returned to Caracas

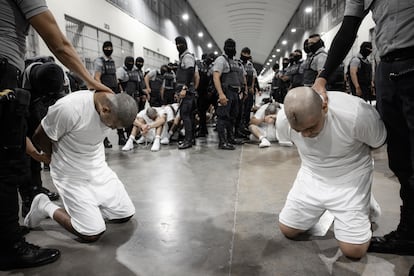

Photos of Luis missing a front tooth and Daniel’s nose with a visibly deviated septum are among the evidence included in the Human Rights Watch (HRW) report “You Have Arrived in Hell,” released Wednesday. The report reveals torture and other abuses against Venezuelans at the Terrorism Confinement Center (Cecot), President Nayib Bukele’s mega-prison in El Salvador. Also included are images of the scars on Mateo’s hand and Carlos’s chest, the result of being shot at close range with rubber bullets while detained in cells at this prison.

The aftermath is still visible almost four months after 252 Venezuelan migrants survived the worst of the nightmare. U.S. immigration authorities detained them at different times, in various cities, and under different circumstances — raids, arrests at their homes, and while crossing the border — and on March 15 of this year, President Donald Trump decided to send them to the feared prison in El Salvador, invoking the Alien Enemies Act and accusing them of being members of the Tren de Aragua criminal organization. They experienced horror, including daily beatings. Following an agreement between governments mediated by the Catholic Church, on July 18 they were finally sent back to Venezuela, a country some of them had left long before, in some cases fleeing political persecution. In exchange for the Venezuelans, the government of Nicolás Maduro handed over 10 imprisoned Americans to Washington.

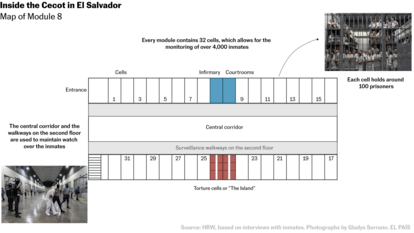

HRW, relying on the NGO Cristosal, research centers, official documents, and forensic specialists, reconstructed the Cecot torture system based on the testimonies of Venezuelans who spent four months and three days in a facility designed to make escape virtually impossible. The report protects the identities of the 40 victims who were interviewed directly, as well as dozens of family members, friends, and lawyers consulted to build the cases of 130 of the 252 Venezuelans the Trump administration sent to the Central American prison. Their names have been changed for fear of reprisals and because several of them have filed lawsuits against the governments of the United States and El Salvador.

Daniel’s nose was broken after he participated in interviews conducted by International Red Cross staff with a group of Venezuelan prisoners on May 7. They beat him with a baton and hit him in the nose, causing it to bleed profusely. “They kept hitting me, in the stomach, and when I tried to catch my breath, I started to choke on the blood [...] My nose stayed crooked from those blows,” he states in the report.

He wasn’t the only one. “After the interview, in the afternoon they came to take us out of the cell for a search and beat us again, telling us it was because we had told the Red Cross about the beatings,” said Félix D. “They only beat me that same afternoon, but some of my cellmates were beaten throughout the following week.” The psychological torture, however, was what affected them the most, said Flavio T: “The hardest part was that the guards told us we would never get out of there, that our families had given us up for dead.” A phrase they frequently heard was that “the only way to get out of here [the Cecot] is in a black bag”; that is, dead. All 252 Venezuelans survived to tell their story.

The worst beatings

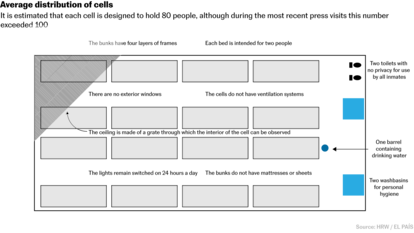

In the days leading up to visits, such as the three by the Red Cross in May and June or the visit by U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem in March, they were given bedding, pillows and toiletries to improve their living conditions. After the visitors left, the items were taken away, and the beatings intensified. Two or three days before they were finally sent to Venezuela, their treatment improved again, but they were also subjected to their last beatings.

As soon as they got off the plane upon arrival, the guards started beating them. “[An] officer hit me in the face with a black baton, right in the mouth, and knocked out one of my front teeth,” Luis S. recounts. Other officers also punched him in the ribs and hit him on the right knee with a stick. “The doctor who saw me about a week later in prison told me that they had ruptured my [knee] ligament. They didn’t give me anything for my tooth,” he stated, according to the report.

The investigation also documented sexual violence. One detainee, Mario J., said four guards sexually abused him when they took him to an isolation cell called “the island,” where those deemed to have broken the rules were regularly punished with further beatings, solitary confinement, and deprivation of food and water. “They played with their batons on my body,” he said. “They stuck the batons between my legs and rubbed them against my private parts.” Then they forced him to perform oral sex on one of the guards, groped him, and called him “faggot.” Another detainee, Nicolás, said he was sexually assaulted during the beatings. Officers grabbed his genitals and made sexually explicit comments. “They did this to several of us,” he said. “I don’t think the others will tell you that because it’s very intimate and embarrassing.”

HRW notes that “the beatings and other abuses appear to be part of a practice designed to subjugate, humiliate, and discipline detainees through the imposition of grave physical and psychological suffering.” According to HRW, the guards, both men and women, wore grey or black uniforms, kept their faces covered and identified themselves by nicknames such as Satán, El Tigre, El Cuervo, Vegeta and Pantera. And they had complete authority to treat the prisoners as they did. “The brutality and repeated nature of the abuses also appear to indicate that guards and riot police acted on the belief that their superiors either supported or, at the very least, tolerated their abusive acts,” the report states.

Limbo in three countries

According to Human Rights Watch, the Cecot prison fails to meet several standards of international human rights law and the Mandela Rules, which aim to guarantee humane treatment for detainees. Opened by Nayib Bukele in January 2023 during a declared state of emergency, it has become a torture machine that is part of the Salvadoran president’s institutional apparatus. There is a history of serious human rights violations committed in this prison. “The United States sent the 252 Venezuelans to Cecot despite credible prior reports that torture and other abuses were taking place in El Salvador’s prisons. This violates the principle of non-refoulement [which forbids a country from deporting a person to any country in which their life or freedom would be threatened] established in the Convention against Torture, among others,” the organization denounces.

Almost everything about the process was irregular. The governments of the United States and El Salvador refused to disclose information about the whereabouts of the 252 migrants, or their fate, to the point that their actions — or lack thereof — constitute the crime of enforced disappearance under international law, the report states. This crime occurs when a government detains a person and refuses to provide information about their location or fate, leaving them without legal protection and causing further suffering to their families. The detention of the Venezuelan migrants at the Cecot facility also lacked any legal basis, making it arbitrary under international humanitarian law, HRW asserts.

Once detained at the Cecot, the Venezuelans were unable to contact with their families or lawyers. Neither San Salvador nor Washington ever published an official list with the names of those affected, nor did they confirm the unofficial lists that were circulating. U.S. immigration authorities had assured the group members that they would be returned to Venezuela. None of those interviewed were informed that their true destination was El Salvador.

For the families, a particular version of hell was beginning, with no knowledge of their loved ones’ whereabouts and bureaucracy transformed into an instrument of psychological torture. The names had been deleted from the computer system containing the detainees’ locations shortly after the transfer to El Salvador and, apparently, “sooner than is standard ICE practice.” The American lawyers representing some of them allege that immigration authorities never informed them of their clients’ transfer.

The families found themselves trapped in a system where, when they managed to speak with someone to request information at ICE offices or detention centers, the officials’ responses were disheartening: either their loved one’s name was not in the system, or their whereabouts were unknown, or they could not be provided with any information. In the best-case scenario, they were told that their relative had been deported, although they were not told where. For some, the only solution suggested was to contact “the Venezuelan embassy in the United States,” even though it has been closed for years.

Attempts to contact the Salvadoran presidential commissioner for human rights, Andrés Guzmán Caballero, by email only resulted in an automated message: the request had been forwarded to the “competent institutions.” After that, there was no further response.

HWR underscores that Salvadoran courts also refused to provide information on the whereabouts of the Venezuelans. Between March and July, Cristosal helped detainees’ relatives to file 76 habeas corpus petitions before the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court, without receiving a response. At the end of March, El Salvador’s General Directorate of Prisons told this organization that the list of people affected by this measure had been declared confidential for the next seven years and therefore it could not release their names. To the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, El Salvador asserted that they had not detained the Venezuelans, but rather had “facilitated the use of the Salvadoran prison infrastructure for the custody of persons detained within the scope of the justice system and law enforcement of that other State,” meaning the United States.

With their release, only part of the nightmare has ended for these men. “I’m on alert all the time because every time I heard the sound of keys and handcuffs, it meant they were coming to beat us,” Daniel B. told HRW. The detainees said they have been psychologically scarred by their experiences. In Venezuela, they underwent medical examinations, interviews with state media, and background checks before being taken home. They have not received psychological support to cope with the ongoing trauma. The report notes that two detainees stated that agents from the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN) visited their homes after their return. “I am currently living in fear,” said Félix D. According to the report, the agents said the visits were “part of a monitoring process.” They asked the released Venezuelans to record videos about their detention in the United States, the treatment they received, and questioned them, among other things, about whether they had connections to U.S. agencies seeking to “destabilize the government.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.