Gazans search for their dead under the rubble: ‘It’s a tragedy for which there are no words’

Many of the bodies of the approximately 14,000 people buried under the ruins of the Strip will never be recovered

A cruel twist of fate meant that Hussein Owda’s children ran ahead to enter their home in Jabalia, in northern Gaza, on May 17. Barely having crossed the threshold, an Israeli airstrike destroyed the building. The man rushed inside. Screams could be heard. His wife, badly injured, was pulled out alive, but their son Mohamed, four years old, was dead in her arms. None of the three children survived.

The parents were only able to bury the youngest. Jaled, 10, and Yusef, seven, remained trapped under the rubble. The bombings continued; Civil Defense rescuers, without excavators, “could not lift” the mountain of debris covering the two children with their bare hands. Sixty-five days later, Hussein Owda managed to recover Yusef’s body — but not Jaled’s. His family had to flee the now-razed Jabalia, leaving their eldest child buried there.

As soon as the ceasefire in Gaza took effect on Friday, residents like Owda began searching for their dead to do what until now they had been unable to: bury them and mourn in peace. In the first 24 hours alone, Gaza Civil Defense recovered 151 bodies. Some were decomposed and lying in the streets, reduced to skeletal remains. Another 116 had been trapped under rubble since the first Israeli bombings, which reached their two-year mark on October 7.

No one knows exactly how many of these invisible dead are. They are not included in the official list of more than 67,000 fatalities, compiled by the Gaza health authorities. It is, however, assumed to be thousands. In April, the United Nations estimated that the remains of 11,000 people were still buried under Gaza’s rubble. Civil Defense believes the number exceeds 14,500, explains Mahmoud Basal, the spokesperson for the body responsible for rescuing survivors and those less fortunate, by telephone.

Many of these bodies will never be recovered. Civil Defense has repeatedly described how Israeli army bombs weighing up to a ton dropped on densely populated urban areas in Gaza simply pulverized buildings and people. Other Palestinians were buried under sites that were bombed repeatedly, and later leveled by military bulldozers, turning the land into a tabula rasa.

In April, a preliminary United Nations assessment of damage in Gaza estimated that 92% of buildings — about 175,000 structures — were completely destroyed or damaged, leaving behind over 53 million tons of rubble, more than all the war debris generated by all conflicts worldwide since 2008. On average, each square meter of Gaza contains 383 kilograms of construction debris. Thousands of bodies lie beneath it.

In Gaza, Israel has not only demolished buildings, but has also put up new structures — sometimes using rubble from bombed sites that may have contained unrecovered bodies — according to architect Eyal Weizman, speaking from London. The director of Forensic Architecture cites examples such as “military bases” and “roads made from compacted debris.”

As if a metaphor for the dehumanization of Palestinians — for that spilled blood “that comes so cheap,” as one crying Gazan said in a video circulated on social media — these new Israeli constructions almost literally bury the bones of some Gazans.

Many of the destroyed buildings were family homes. In traditional cultures like Palestine’s, especially during a military attack, women and children spend more time indoors. Half of Gaza’s population is under 14 years old. In the official lists of more than 67,000 deaths, more than half are women and children; that proportion rises to over 70% among those buried under the rubble, according to the Civil Defense spokesperson. In images of the more than 150 bodies recovered in the first hours of the ceasefire, there were bodies of young children.

Without saying goodbye

Hussein Owda, 33, lost his daughter Iman, who would now be nine, in an airstrike in October 2023, and in May he lost Mohamed, Yusef, and Jaled. If there is any hatred in him, it’s not noticeable. What is evident is a pain that is difficult to measure, especially for Jaled, the child buried beneath the rubble.

“I feel helpless and devastated,” he says. “I haven’t even been able to bury my son, who is still under the rubble. It’s indescribable, a tragedy for which there are no words,” mutters this father who, before the invasion, earned his living as a professional bodybuilder.

Muslims believe that burying the dead is a sacred duty. Islamic rituals, like those of other religions, serve as a way to say goodbye; to “symbolically close the passage of a person through the world and begin the grieving process,” explains Palestinian psychologist Fidaa al Araj from Deir el-Balah, in central Gaza.

The trauma suffered by tens of thousands who have been unable to say goodbye to their loved ones is compounded by the fact that many of the deceased were children, like Jaled Owda. This grief is further intensified by successive forced displacements, notes Al Araj.

The Israeli attacks and bombings, which have now ceased, along with constant evacuation orders, forced people like Owda and his wife to leave their children’s bodies behind. This produces, according to the psychologist, “a feeling of having abandoned them.”

Some Gazans already know it will be impossible to recover their dead, that even the rubble of their homes has been pulverized. Others are discovering this now as they return to their places of origin. The Jabalia refugee camp, where the Owda family lived, is one of those landscapes of absolute desolation left behind by the Israeli military.

Nothing left to remember them by

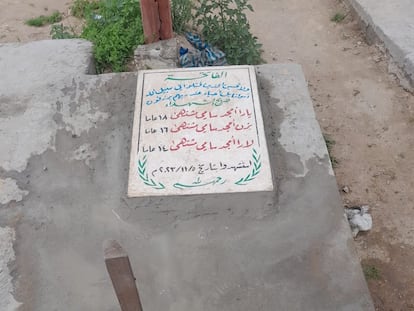

Yara, Yazan, and Lara Mushtaha smile, seemingly happy, in a family photograph — one of the last selfies these three middle-class teenagers took together before an Israeli missile destroyed their home in Gaza City, killing them on November 5, 2023.

Their family was only able to recover the body of Yara, 18, who was on the ground floor, recounts their aunt Malak, speaking from Granada in Spain, where she now lives. The two younger siblings, 15 and 14, were on the first floor and could not be found. With the ceasefire in place, their family will not search for them, Malak explains. They already know it is “impossible” to find them.

After the first missile strike, the Israeli army bombed the Mushtaha home again. Still, the family searched for Yazan and Lara for months. When their mother, who survived the attack, was able to return one last time, she found a shapeless heap of rubble. She no longer even hoped to recover their children’s bodies; she only wanted “a memory of them, a photo, a piece of clothing,” writes Malak in a message. She found nothing.

Ghada Rabah, a 27-year-old English teacher, survived the bombing of her home in Gaza City in September. Buried alive under the rubble, she called her relatives for help.

Many desperate people phoned Civil Defense that day. Friends, neighbors, and family members, recalls the spokesperson: “They told us that Ghada was alive under the rubble and that they were speaking to her on the phone.”

“We asked permission [from the Israeli army] through the Red Cross and OCHA [the U.N. humanitarian coordination body] to reach the house [which was in an area declared off-limits by the military]. We had information that Ghada was with several children and another member of her family,” Basal recalls.

Israel took three days to authorize the rescue. By the time Civil Defense arrived, a second projectile had wiped the house off the map, says Basal.

Bare hands

Civil Defense also faces the daunting task of removing tons of rubble practically with its bare hands.

“We’re talking,” says Basal, “about bombed multi-story buildings that trapped their inhabitants beneath them.” Rescuing the living or recovering the dead requires “heavy machinery and professional rescue teams.” Civil Defense had 820 rescuers when the Israeli offensive began. Now, only about 500 remain, plus volunteers, after Israeli attacks killed 140 and injured several hundred, Basal explains.

Until now, he explains, “the occupation [Israel] had categorically refused to allow the entry of fuel or equipment [such as bulldozers] into Gaza.” The result is that, instead of rescuing someone “in 10 minutes,” it took hours for Civil Defense to reach the victims of a bombing. “Sometimes we heard the screams of living people, but by the time we got to them, they were already dead,” the rescuer laments.Some of the people whose remains families are now searching for might have been saved, says Basal.

During the previous ceasefire, between January and March, when the recovery of buried bodies began, “only nine bulldozers obtained Israeli permission” to enter the Gaza Strip, the spokesperson recalls. Afterward, Israel “bombed and destroyed them all.”

Fuel began arriving in Gaza this weekend, but the territory’s Civil Defense has “no machinery,” not even a single excavator, to try to recover the bodies.

“We are forced to work with our bare hands or with completely inadequate primitive tools,” Basal says by phone.

Last week, Egypt began pressuring Israel to allow excavators in. There are some in Gaza — not belonging to Civil Defense — but the priority right now is saving lives, and they are being used to clear roads of rubble to allow humanitarian aid trucks through.

In an almost desperate attempt to ensure that the memory of their loved ones did not vanish completely, before fleeing the bombings, many Gazans wrote the names of their dead on the walls of houses that had succumbed to the bombs. On February 19, the Mushtaha family exhumed Yara’s body from a temporary burial. In her grave at the Ali ibn Marwan cemetery, only the young woman lies. A single tombstone bears three names: hers and those of her siblings, Yazan and Lara, who disappeared beneath the rubble.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.