The battle for sand: Murders, impunity and environmental destruction in the Dominican Republic

The illegal extraction of materials from rivers, which are later utilized for construction in a process that’s organized by mafia-like groups, exposes the lack of state control in the country

Like something out of an old Western, an empty shack guards the entrance to the Nizao River. This particular stretch runs through El Roblegal, in the Baní municipality, located in the southern Dominican Republic. Sometimes, residents say, an armed guard controls the passage and only allows trucks and heavy machinery to enter. Around 25 dump trucks enter and leave, loaded with sand and gravel, to be used for construction. They raise a cloud of dust among stones and stagnant puddles. It’s evidence of an ecocide that is slowly causing the river to disappear.

“Decades of indiscriminate exploitation have caused severe over-excavation of the riverbed, sinking its bed and collapsing its banks,” biologist Luis Carvajal explains. He’s a member of the Dominican Republic Academy of Sciences and coordinator of the Environmental Commission at the Autonomous University of Santo Domingo (UASD).

Three young men on motorcycles patrol the area, watching for possible intruders. A backhoe roars, while a power shovel loads a truck. While attempting to record the scene, a man violently snatches the cell phone away from this reporter.

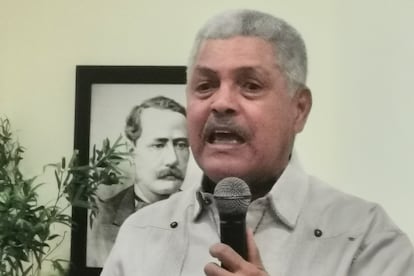

Milcíades Martínez — a representative of the Dominican Revolutionary Party (PRD) in the community of Pizarrete, which borders the town of El Roblegal — approaches the scene. Martínez demands identification from EL PAÍS. And, despite ordering that the cell phone be returned, she harasses this journalistic team, ushering us back to our vehicle: she claims that our presence is a violation of “private property rights.” However, there are no signs indicating this.

The scene takes place just a few feet from the riverbed and two operating machines. Francisco Contreras — head of the Specialized Attorney General’s Office for the Environment and Natural Resources (Proedemaren) — assures EL PAÍS that the Nizao River is constantly monitored by the National Environmental Protection Service (SENPA), an institution belonging to the national army. However, no authorities were observed in the area during the visit. “I understand that [the man who snatched the phone] operates on a nearby farm. The problem is that, sometimes, they obtain permits and then violate them, even at night,” Contreras admits.

Dominican law establishes a 100-foot buffer zone around rivers and streams. However, both Minister of Environment Paíno Henríquez and Attorney General Contreras agree that, in cases like that of the Nizao tributary — weakened by constant land grabs — it should be extended to 1,000 feet.

Furthermore, the law prohibits the extraction of aggregates, but allows concessions under certain conditions, which creates contradictions. Since 1986, successive governments have attempted to curb the activity with decrees and agreements that have never been enforced. Today, in theory, the practice is completely banned. But despite prohibition measures, the problem persists.

The illegal mining business operates at gunpoint

President Luis Abinader has compared the illegal granceras business (open-pit mining) to drug trafficking. As a deterrent, he has authorized more permits for dry quarries, as well as the use of sediment extracted from dams as an alternative for the construction sector.

The Nizao River is an emblematic example of the indiscriminate extraction of construction materials. This practice also affects other tributaries, such as the Yuna in the north, the Tireo in the Central Cordillera and the Yaque del Norte and Guayubín, both in Montecristi — a coastal city bordering Haiti — among many other tributaries. The water security of numerous communities is compromised in the Caribbean country.

According to the environment minister, tax evasion and low regulatory costs allow illegal aggregates to be sold below market prices, “generating considerable profits.” The total amount of material on a 700-cubic-foot truck can cost between 20,000 and 22,000 Dominican pesos ($325 to $358).

Paíno Henríquez estimates that the business of what are known as legal and illegal aggregates generates around $1 billion a year in the Dominican Republic, equivalent to more than 1.76 billion cubic feet of sand.

“Some quarries extract up to 423,000 cubic feet per day. In the informal market, 35 cubic feet sell for between 500 and 1,500 pesos [between $8 and $25], while in the legal sector, it ranges from 1,800 to 2,200 pesos [$30 to $45]. This fuels a black market that affects formal businesses,” he explains.

The dangers of reporting

Activist Manuel Antonio Nina — from the Vida Ecological Movement in the province of Peravia — denounces that even legal mining companies breach their environmental permits. He recalls that, back in 1998, farmer Sixto Ramírez was murdered after reporting illegal mining operations at the Alba Sánchez mine, which currently continues to exploit resources in the area.

Reporting the crimes remains dangerous. This past February, Alexis Rodríguez — a former baseball player — posted a video on TikTok. The footage showed illegal operations on the Nizao River, as it passed through the community of Don Gregorio, in the municipality of San Cristóbal. Shortly afterward, he received death threats and was extorted by men at gunpoint, as he recounted to EL PAÍS.

According to his account of events, the criminals demanded 33,000 Dominican pesos ($560), an amount similar to the official fine imposed by the Public Prosecutor’s Office. “I was forced to rent out my food business: [it] operates on the banks of the river, where there are about 200 similar stalls that make a living from tourism,” says the young widower and father of five. Since then, he has kept a low profile.

A worse fate befell farmer Francisco Ortiz, who was murdered on April 11, 2024, after trying to stop illegal extraction in the Tireo River. He was shot four times, beaten with a shovel and incinerated. His ashes were buried 186 miles from the crime scene.

Three people are facing trial, but the process has been criticized for excluding environmental charges. When contacted by EL PAÍS, the minister of the environment and the head of Proedemaren said they were unaware of this omission. “In the Dominican Republic, cases are judged according to the most serious crime,” Attorney General Francisco Contreras explained.

Juan Ortiz — the victim’s brother — reported that a judge recently reclassified the crime as simple homicide, excluding premeditation and criminal association. Activists argue that the perpetrators are benefiting from double impunity.

Initiatives and challenges in the face of organized crime

Violence is common when it comes to illegal mining in the Dominican Republic: threats and gunshots targeting environmental activists, journalists, inspectors and army personnel have been reported, as well as murders. Environmentalist Manuel Nina warns that “these mafias sometimes have the support of politicians, officials, and even members of the National Environmental Protection Service [SENPA].” Representatives of the institution declined to comment.

One example is the dismantling of a network led by former military personnel earlier this year. It operated for 15 years in the community of Muchas Aguas, San Cristóbal, in the south of the country, illegally extracting minerals from the rivers.

This past April, Bernardo Alemán — a senator from Monte Cristi — went before the upper chamber and denounced the alleged complicity of local authorities in the illegal extraction of aggregates from the Guayubín and Yaque del Norte rivers. He reported that more than five backhoes operate in these areas and that about 100 dump trucks pass through daily —allegations that reveal the organized nature of the business.

In April of last year, the provincial director of the Monseñor Nouel region irregularly granted a permit to the Maimón Mining Consortium, which ended up drilling into the Yuna River’s water table. As part of an agreement with the Specialized Attorney General’s Office for the Environment and Natural Resources (Proedemaren), the company agreed to reforest 3,000 trees, pay a fine of three million Dominican pesos (almost $50,000) and operate under environmental supervision, according to statements made by Contreras to EL PAÍS.

Violence also affects the public authorities. In January, SENPA agents were ambushed in San Cristóbal after seizing a truck: it was carrying sand that had been obtained illegally. An armed group intercepted the vehicle, held the agents at gunpoint and recovered the cargo. The scene was recorded and shared on social media.

According to Proedemaren, several operations have been canceled due to threats to the safety of its officers. Its director laments the low budget and shortage of personnel: he warns of the urgent need to create an investigation unit — under the National Police — to work with the Public Prosecutor’s Office on environmental crimes. “Only in this way can we get to the root cause and arrest the leaders of these mafias, who are big businessmen,” Contreras argues.

For its part, the Ministry of the Environment is developing a traceability platform — using satellite and GPS technology — to identify those who profit from illegal extraction, according to Minister Henríquez. The institution is also promoting ecological restoration programs, payments for environmental services rendered and a legal reform to toughen penalties.

Ecological, social and economic impacts

The depletion of rivers has severe ecological consequences. However, beyond the ecocide, Patricia Abreu — executive director of Santo Domingo Water Fund (FASD) — warns about the social and economic impacts: “Many communities are seeing their water sources — which are essential for consumption and agriculture — contaminated or reduced, which generates human displacement and puts food security at risk.”

A critical case is the Dajabón River, also known as the Massacre River. On the border with Haiti, its possible disappearance — due to the diversion of water from the neighboring country and the looting of materials on both sides of the island — threatens to force the migration of entire communities. “There are already dry wells and [water] shortages for livestock in Dajabón,” biologist Luis Carvajal decries.

Uncontrolled extraction is also puttin vital infrastructure at risk. In May 2024, a slurry mine in San Cristóbal undermined the ground beneath electricity pylons, requiring emergency intervention. Such issues come with a public cost. In 2022, the Dominican government announced an investment of more than 133 million pesos ($2.2 million) to improve the Nizao River to prevent flooding.

“We need educated and empowered citizens who don’t become accomplices of those who destroy rivers for profit. Only with civic awareness can we stop this depredation,” says Contreras.

The urgency is evident in the face of the devastation caused by aggregate extraction: altered ecosystems, endangered crops, heavy machinery operating without state oversight and murders that have gone unpunished.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.