Sperm donor scandal rocks The Netherlands: ‘There could be thousands of children with more than 25 siblings’

In the wake of repeated breaches of donation limits, authorities introduced a national registry to ensure clinics can monitor and coordinate sperm donations

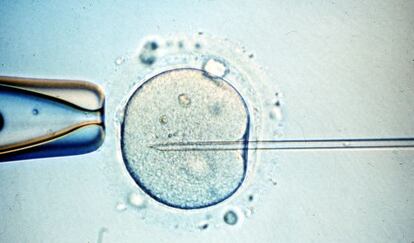

For 20 years, fertility clinics in the Netherlands failed to comply with sperm donation guidelines, resulting in at least 85 mass donors — each fathering between 26 and 75 children. Between 2004 and 2018, regulations limited each donor to a maximum of 25 offspring. Since 2018, the cap has been reduced to 12. This widespread breach came to light following the launch of a national sperm donor registry in April, offering the first comprehensive overview of donations since the 2004 Artificial Insemination Donor Data Act banned anonymous contributions.

The Professional Association of Gynecologists (NVOG) has confirmed these findings, including evidence that some donors were active simultaneously at multiple clinics. The poor oversight of specialized clinics, along with the existence of the 85 mass donors, was revealed by the television program Nieuwsuur on the public broadcaster NOS. On Monday, the NVOG issued a statement acknowledging that “in some cases, the previous limit of 25 children, and then 12, per donor has been exceeded.”

NVOG admitted that the new registry uncovered an additional issue: donated sperm had been exchanged between clinics without any exchange of donor data — possibly due to privacy concerns. The NVOG emphasized that, prior to the establishment of the national registry, fertility centers had no means to cross-check donor usage across different clinics. Once irregularities were detected, the clinics ceased using the affected donors. In the Netherlands, sperm donation is unpaid, with donors receiving a maximum of €40 to cover travel expenses.

The Donorkind Foundation, which helps donor-conceived children and siblings connect, condemned the conduct of fertility specialists. “All of this has happened for two reasons: because of the money these clinics receive for their treatments, and because the impact of mass donors on the lives of mothers, their children, and the siblings of these children has not been taken seriously,” said Donorkind’s president, Ties van der Meer, in a phone interview.

He believes the actual number of children fathered by the 85 donors may be underestimated. “There could be thousands of children who have more than 25 siblings and half-siblings,” he said, calling the situation incomprehensible. Van der Meer criticizes how fertility doctors have framed donor-conceived relationships. “The problem is that the doctors at these assisted reproduction centers present the family bond resulting from sperm donation as a simple genetic fact,” he said. “The donor is not a father, and neither are the other potential siblings, and the importance of the basic truth that a family is more than just DNA is diminished.”

As both a donor child and a donor himself, Van der Meer indicates that the government has realized the importance of informing families about the details and scope of sperm donations. He adds that the families of the 85 donors will be informed shortly and asks those affected to contact the foundation —which is run by volunteers — “because we already know that some families are in favor of the government funding any psychological help they may need.”

With a population of 18 million, the situation raises further concerns: “Donor children, if they enter into a relationship, will have to undergo a DNA test to rule out possible blood ties,” said Van der Meer.

Until April, the 2004 Artificial Insemination Donor Data Act maintained a registry of donors’ physical traits, such as eye and hair color. Children could access this information from age 12, and from age 16, they could also request the donor’s name, date of birth, and place of residence. However, donors were not legally obligated to establish contact with their offspring.

Since April, information on both donors and mothers is now collected in a centralized, national registry rather than by individual clinics. The registry is retroactive to 2004 and allows authorities to track how many children were born from each donor. Mothers can now find out how many other families used the same donor. On Monday, the NVOG urged mothers, donor-conceived children, and donors to contact fertility clinics if they seek more information.

The shortcomings of the Dutch assisted reproduction system have already led to several high-profile scandals. In 2023, Dutch courts imposed precautionary measures on Jonathan Meijer after a mother filed a complaint. Meijer had falsely claimed he had fathered no more than 25 children, despite having donated at 11 fertility clinics between 2007 and 2017 and fathered 102 children. Although he was banned from donating in the Netherlands in 2017, he continued offering his services internationally via online platforms. He is now believed to have fathered up to 550 children across several countries, including Spain.

Another notorious case is that of gynecologist Jan Karbaat, who died in 2017. He is now credited with fathering at least 105 children after secretly using his own sperm to inseminate patients at his clinic in Rotterdam. Karbaat operated the clinic for four decades, during which his patients believed they were receiving sperm from anonymous donors.

In 2021, it was revealed that gynecologist Jan Wildschut had fathered at least 40 children between 1981 and 1993 while working at a hospital in Zwolle. Then, in 2022, it emerged that a third gynecologist, Jos Beek, had fathered at least 41 children using his sperm between 1973 and 1998 at a regional hospital in Leiderdorp. Beek carried a hereditary disease that could be passed on if the mother has the same gene, according to FIOM, the national foundation specializing in the freedom of choice in cases of unwanted pregnancies and the right to information about paternity.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.