Trump’s Ecuadorian deportees: Returning to a country under the terror of organized crime

Immigrants expelled by the United States once again face a gang-dominated society where extortion and homicide are the norm

When the extortionists arrived at Elena and Ramiro’s small food stall in the heart of downtown Guayaquil, they knew their dream of entrepreneurship had come to an end. The business, which had only been operating for five months, was doing better than expected. They served breakfast and lunch to workers, and although margins were tight, the hope of a prosperous future kept them afloat. But that morning, when two men who arrived on a motorcycle burst into the establishment, what promised to be just another day of work turned into a nightmare. They made it clear what the rules would be from then on: $3,000 a month as a “vaccine,” as extortion is known in Ecuador. An unaffordable sum for entrepreneurs whose only capital was the sweat of their brow.

When Elena heard the criminals tell her where she lived, details about her house, and about her and her family’s movements, she knew she wouldn’t wait for them to keep their promise to close down the business. She understood there was no turning back; they had to leave the country. Two weeks later, with a debt of $17,000, she, her boyfriend Ramiro, and three of his relatives boarded a flight to El Salvador. It was the first step toward escape.

On December 9, her journey through Central America began, with the ultimate goal of reaching Ciudad Juárez and crossing into the United States. Ten days later, her group reached the final stop, where a coyote (human smuggler) promised to help them cross the border, underground, beneath the wall, more than eight meters high. Just a few hours later, immigration authorities captured them.

Elena painfully recalls the blow from one of the officers: “He punched me, and that was it,” she says, while waiting for someone to pick her up at the Guayaquil airport, where she arrived as a deportee due to the mass expulsions implemented under Donald Trump’s immigration policy. She was dressed in a gray overcoat and a fleece jacket, wearing shoes without laces; she had only learned the night before that she would be deported. She traveled on a charter flight, along with about 100 other Ecuadorian migrants, who also failed to evade immigration patrols.

Since the beginning of the year, more than 1,900 Ecuadorians have been deported from the United States, a number that adds to the 43,000 who have returned in the last four years, as part of a returnee agreement that both countries have maintained since 2005. The deportations, far from being an isolated incident, are part of a routine: two or three flights per week, according to the Ecuadorian Foreign Ministry.

On the plane, Elena met Jennifer, a 25-year-old woman. They had both been in the same detention center in Louisiana, but the strict rules of confinement and total isolation prevented them from meeting or speaking. It was only then, sitting at the airport waiting for someone to pick them up, that they discovered they shared a similar reality. They both migrated out of fear of violence; they both came from the same neighborhood, Guasmo Sur. The connection was immediate, but Jennifer’s journey had been even more brutal. She had spent five days as a hostage of one of the criminal gangs in Oaxaca, Mexico.

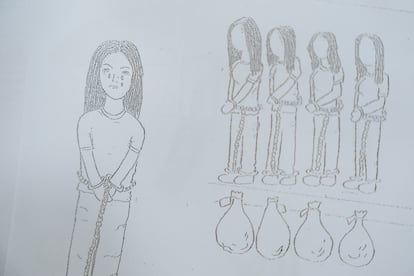

“I spent all those days in silence, wearing baggy clothes, afraid of seeing them take the girls to be raped,” the young woman says. After being released, she managed to cross the border and surrender to U.S. Border Patrol agents, who shackled her and then released her in San Diego, where she remained for three weeks. At her last hearing, it was decided she would be sent to the “icebox,” the detention center in Texas, and then she was transferred to Louisiana, from where the flight that would bring her back departed.

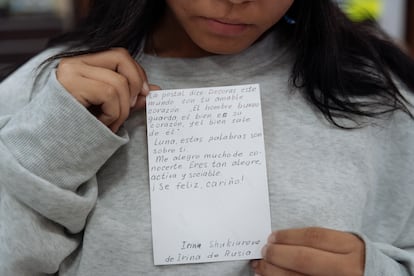

She doesn’t have a cent. Jennifer, visibly worried, has just received the news that her two-and-a-half-year-old son is sick. All she has is a card with $50 on it that the World Food Program gave to each migrant upon arrival at the terminal. She was also told about a website where she can register to receive $470 for three months, as part of the aid the Ecuadorian government offers deported migrants. However, that prospect seems uncertain.

Upon arrival at the Guayaquil airport, the deportees stand out from the crowd. Their pale faces, marked by fatigue and confinement, reflect the frustration of those who didn’t find what they were looking for in the north. However, many try to hide their pain and, upon first contact with their families, display a smile despite the tragedy: “Guess where I am!” they say, only to confirm what they already know: they have returned to Ecuador. But there is no one waiting for them. Neither friends nor family have been alerted to their return. They are alone, worried, in debt...

Elena hasn’t checked her phone since December 19, the day she was arrested. She’s been cut off from her family and boyfriend Ramiro — who was deported in January — all this time. She doesn’t know what’s happening in the country. “I guess everything’s worse,” she admits with bitter certainty.

She is unaware of the shooting that occurred in her neighborhood, Guasmo Sur, or that in the neighborhood cemetery, the four children who were disappeared by a military patrol were buried, and that their bodies were later found incinerated in the middle of a swamp.

She doesn’t know about the latest violent deaths that have shaken the city, nor about the massacre of 22 people in the Socio Vivienda 2 neighborhood. Nor that extortion continues to increase, fueled by the fear and helplessness of those unable to pay.

Since Elena left the country, violence has been on the rise. The same violence that forced her to flee has now taken over the streets, turning Guayaquil into a city under siege. The economy, meanwhile, has not improved. Employment remains stagnant, and the basic wage has only increased by $10. Elena returns to an Ecuador overwhelmed, a country on fire.

“Now we have to start from scratch. We sold what little we had, as well as the $17,000 we each owe,” the 20-year-old says, her face creased with disappointment. “I thought I’d have protection in the United States, but they didn’t believe me. I had to say I’d been raped, that I’d been shot, but I chose not to lie,” she says, worried about the debt she must pay.

At that moment, Ramiro arrives at her side. Speechless, they fall into a long embrace. They are both clear about one thing: staying is not an option. Ecuador is no longer a country to live in. Although the future is uncertain, they both know the only way forward is to leave. They will start over, somewhere else, but far from here.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.