North Korea’s involvement in the war in Ukraine worries its Asian neighbors

Possible technological transfers from Moscow to Pyongyang are a concern fo Seoul and Tokyo, while Beijing juggles its interests to remain equidistant

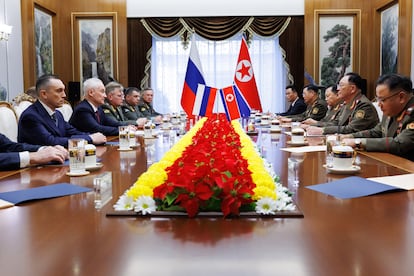

The Moscow-Pyongyang axis is causing concern in the Asia-Pacific region. North Korea’s direct involvement in the war in Ukraine and the increasingly harmonious dance between Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un is sending seismic waves from Europe to the other side of the great land mass. If the presence of elite North Korean soldiers in live-fire combat in Ukraine, already confirmed by Kyiv and Western intelligence servies, represents “a significant escalation” of the war on the Western front, as defined by NATO, on the Asian flank there is particular concern about possible technological transfers from Moscow to Pyongyang in the ballistic and nuclear fields, due to their potential to destabilize conflicts already entrenched in the region, such as that of the two Koreas or Taiwan. The dismissal of South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol following his failed attempt to impose martial law adds a further element of uncertainty and instability that benefits the interests of the Russia-North Korea axis.

For Kitamura Toshihiro, director general of press and public diplomacy at the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the presence of North Korean soldiers on the Russian front is “a clear example” of how “interconnected” the security threats in Asia and Europe are. The concern goes beyond the fact that Pyongyang is receiving high-quality Russian technology: “If North Korean soldiers return, they will do so with real combat experience,” he warns. This is something that has not happened since the Cold War: North Korea has not participated in a direct war since the one it fought against South Korea between 1950 and 1953; the South Koreans have not done so since they sent troops between 1964 and 1973 to the Vietnam War (1955-1975).

“Everything is getting complicated,” says a European diplomatic source based in Beijing. Kyiv and Seoul confirmed weeks ago that North Korean soldiers had been killed in the Russian province of Kursk, after British Storm Shadow missiles were fired; at least 100 soldiers from the Asian country have died and 1,000 have been wounded, according to a South Korean parliamentarian who was informed this week by Seoul’s intelligence services. For the European source, the new alliance between Kim and Putin, sealed in June and in force since the beginning of December, implies an even greater risk to security than the Russian leader’s redoubled nuclear threats. This “strategic partnership agreement” includes a pact of “mutual defense in the event of aggression.”

South Korea interprets North Korea’s involvement in the war in Ukraine as a direct threat to its security. “We do not rule out the possibility of supplying weapons. We would give priority to defensive weapons,” Yoon said in early November, when he was still in charge of the country. This is something he had not done until now, limiting himself to non-lethal aid shipments. A week before declaring martial law, the South Korean leader met in Seoul with a Ukrainian delegation led by Defense Minister Rustem Umerov, to whom he emphasized the commitment to seek “practical response measures” and with whom he agreed to “continue sharing information on the deployment of North Korean troops and the transfer of weapons and technology,” according to an official statement.

The debate, according to Ramón Pacheco Pardo, a professor of international relations at King’s College London who specializes in the Korean peninsula, was whether Seoul would decide to transfer its anti-missile shield system to Ukraine, and even its weapons. The consequences of this “more direct involvement” are unpredictable. The Kremlin warned Seoul, through Andrey Rudenko, deputy foreign minister, to “seriously evaluate the situation” and refrain from “taking reckless steps,” according to the Russian news agency Tass. Sending weapons that kill Russian citizens, he said, would destroy relations between the two countries. “We will respond in any way we consider necessary,” he added.

The political crisis that has shaken South Korea has frozen the debate. Yoon, who was dismissed last Saturday by the National Assembly, has been removed from power, pending ratification by the Constitutional Court. In the meantime, Prime Minister Han Duck-soo, the second highest authority in the state, has assumed presidential duties. “The South Korean government is functioning, but new initiatives are paralyzed. Whatever was happening, it will not happen until this whole dismissal process is resolved,” says Chun In-bum, a retired three-star general in the South Korean army and an expert on military affairs. “This, in turn, will benefit the Russians and the North Koreans,” he adds. They will buy time. In his opinion, South Korean political instability is bad news for Ukraine, for Europe, and also for Asia. He believes that South Korea’s political and military rapprochement with Japan, led by Yoon under the auspices of the outgoing U.S. president, Joe Biden, will also likely suffer.

The situation comes at an already turbulent time between the two Koreas. Pyongyang approved a constitutional reform in October that omits references to reunification with its neighbor, which it now defines as “the main hostile and enemy state.” In January, the all-powerful Kim had asked parliament to include in the constitutional text the idea of “completely occupying, subjugating and claiming” South Korea and “annexing it” in the event of a war breaking out on the peninsula. At the end of November, the North Korean supreme leader declared that “never” had the confrontation between the two sides “been so dangerous and intense, capable of escalating to the most destructive thermonuclear war,” reported the state news agency KCNA.

A recent article by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace think tank notes that “Ukraine is evolving into an unexpected proxy battlefield for tensions on the Korean Peninsula.” “The Ukrainian theater of operations risks becoming the first direct test of Korean military capabilities since the 1953 armistice, which could radically alter the peninsula’s security balance,” the article warns.

Analyst Pacheco Pardo is also concerned about how the growing rapprochement between Putin and Kim could influence other potential regional fires. If, for example, there were an eventual conflict over Taiwan, the self-governed island that Beijing considers an inalienable part of its territory, the North Korean regime could take advantage of it to create instability with its southern neighbor. “Once North Korea has helped Russia,” he notes, this hypothetical conflict between the two Koreas would force “Russia to support North Korea,” something that before the June pact might not have happened. Pacheco Pardo does not believe it is likely, but, after seeing how Russia invaded Ukraine, it cannot be ruled out that this would give China “ideas,” he says, noting the lack of support from third countries.

This is also a possibility that worries Tokyo. “We are concerned about cooperation between China and Russia,” admits Toshihiro, of the Japanese Foreign Ministry, as well as “Beijing’s growing assertiveness in the South China Sea, especially around Taiwan.” However, Kyoko Hatakeyama, professor of international relations at Niigata Prefectural University, stresses that North Korea and China “are different” and points out that, for the Chinese government, economic development is essential, so it cannot take a decision of this magnitude lightly. “North Korea is not a permanent member of the UN Security Council or a major player in international organizations. China cares about its reputation as a great superpower; North Korea does not,” she notes.

China, which wants to protect its ties with the United States and the European Union, is trying to maintain a balance that is sufficiently far from the Pyongyang-Moscow axis, albeit for show. However, North Korea’s entry into the Russian front — an event to Washington’s distaste — “is not so bad for Beijing,” explains Lee Sung-yoon, an international researcher at the Wilson Center think tank. “China’s biggest strategic competitor is the United States, and having the influence that China has over North Korea [Pyongyang’s main economic support] already gives it a huge advantage when it comes to negotiations,” says the South Korean analyst. “Beijing is looking for the right moment to show itself as a less radical and more peace-oriented nation than Russia and North Korea, but at the end of the day it is the benchmark for this group of autocracies.”

This cocktail of latent tensions, coupled with North Korea’s growing involvement in a conflict taking place thousands of miles away, highlights how regional dynamics are taking on a global dimension. “The United States is more willing to get involved in the Indo-Pacific than in Ukraine,” says General Chun. “North Korea has escalated the scope of the war in Europe and this has made Europe and its allies more aware that North Korea is not just an East Asian problem, but a global one,” he concludes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.