Bhopal: Dark tourism at the scene of the worst industrial disaster in history

Victims’ advocacy organizations continue to demand fair compensation and criticize the tourist use of the factory 40 years after the tragedy. Some 22,000 people have died since 1984, half a million suffer from aftereffects, and this area of India remains a danger to the health of its inhabitants

The tour lasts four hours and costs around $134 dollars per person. “Visit the abandoned Union Carbide factory and the affected neighborhoods nearby to witness the dark side of industrial progress,” explains the tour operator Sita World Tours in an advert posted on Tripadvisor and other tourist websites. The aim is to visit the scene of the worst industrial catastrophe in history, which occurred 40 years ago in the city of Bhopal, where a toxic gas leak killed thousands of people and caused sequelae and congenital damage to more than half a million more.

Victims’ organizations, which are still waiting for official explanations and fair compensation, consider these visits to be disrespectful and a way of exploiting the suffering of those affected.

On the night of 2-3 December 1984, methyl isocyanate (MIC), a highly toxic chemical used by the factory to produce pesticides, began leaking from the warehouses of Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL), the Indian subsidiary of the U.S.-based Union Carbide Corporation (UCC), while the local population living in the slums was fast asleep. The alarm, due to negligence that has not been fully clarified, did not work and the gas cloud had already surrounded the homes and entered the lungs of the inhabitants.

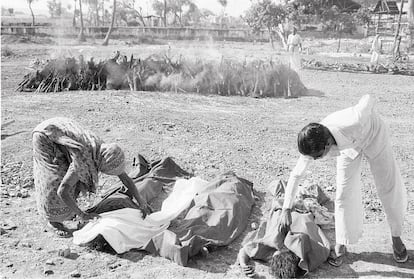

Half a million people were exposed to the chemical and several thousand died that night, from drowning or internal bleeding, and in the days and weeks that followed, with doctors helpless to treat the victims. The Indian government estimated that 3,500 people died in the first few days and about 15,000 in the years that followed. To this day, the figures remain difficult to estimate. According to a recent report by Amnesty International, the death toll from the tragedy is as high as 22,000, of whom 10,000 died on the night of the disaster and in the weeks that followed. In addition, some 500,000 people suffer from some form of aftereffect, such as cancer, respiratory or digestive diseases, hormonal and mental disorders, and congenital disabilities.

“I felt very bad while visiting the factory. Although it’s no longer operational, its legacy continues to haunt the city. The abandoned facility is a reminder of the tragedy and a constant source of pain and anger for the survivors and their families,” Sahitya Sharma, who runs a travel blog and was able to tour the Union Carbide plant, told this newspaper. “It is a potent and haunting symbol of industrial neglect, a place that deserves to be remembered and studied so that future tragedies can be prevented.”

The factory site remains the property of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh and entry is theoretically permitted only for scientific reasons, said a representative of the government office that issues permits.

“Most of our clients are British and American,” one of the tour operators told EL PAÍS, asking that his identity not be published. “We have been doing these tours for about three and a half years. Making money from this kind of disaster tourism is not something I like to do, but I don’t think the local people are unhappy. But of course, when tourists come, old memories come up which can make the survivors upset,” he said. “But the sad reality is that the government is not concerned about them.” Sita World Tours did not respond to an interview request made by this newspaper.

Exploiting the victims

On the night of December 2, 1984, Rashida Bee woke up feeling like she was drowning and heard coughing all around her. Her home was very close to the factory. She was just a child, but she ran, trying to escape until she ran out of breath and lost consciousness. She woke up surrounded by bodies. When she arrived at the hospital she saw dozens of corpses piled up. She lost many family members and friends that night and in the months that followed. Today, she runs the Chingari Rehabilitation Center, which she co-founded. It receives children born with congenital disabilities due to the tragedy.

“How can they use this place to make money? They are exploiting the victims. This cannot be allowed,” she says indignantly, referring to the guided tours of the factory. “The U.S. government has not taken any steps to bring justice to the victims of Bhopal, and now their companies are putting on this show,” she adds bitterly.

Just a few meters away is the office of the International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal (ICJB). On the walls are pictures of disabled children and a photo of Warren Anderson, CEO of Union Carbide at the time of the tragedy. “Fair compensation, when?” reads the posters. “My God, so much money!” says activist Rachna Dhingra, looking at the price of the tours. “This is nothing but a way to make money off the misery of the victims,” she adds.

She bitterly points out that the authorities’ priority has been to retain foreign investment and that they have therefore forgotten to obtain justice for the victims. According to her, Indian leaders are reluctant to prosecute those responsible for Union Carbide in the United States so as not to discourage other companies from investing in India. “The victims of the tragedy are half Muslims and half Hindus from the lowest caste. They are considered expendable,” she says.

“Little has changed in the past 40 years. Unequal power dynamics have ensured that justice is denied to the victims, who predominantly belonged to low-income, marginalized and minority communities. Meanwhile, those responsible, especially giant U.S.-based companies, shamefully continue to evade their clear human rights responsibilities,” said Mark Dummett, Amnesty International’s director of business and human rights, in the organization’s report published to mark the 40th anniversary of the tragedy.

Impunity

In 1989, there was a settlement between Union Carbide and the Indian government in which the company paid $470 million for 102,000 injuries and 3,000 deaths. “This amount was less than 15% of the initial amount claimed by the government and far lower than most estimates of damages at the time. Thousands of claims were not recorded at all, including those of children under 18 exposed to the gas, and children born to parents affected by the gas who, as time later proved, were also severely affected,” Amnesty International criticizes in its report.

At best, victims or their families received around $500. In 2010, a court in Bhopal sentenced eight of Union Carbide’s then employees, all Indians, to two years in prison and ordered them to pay 100,000 rupees (around $1,860) for negligence. However, they were immediately granted bail. The court also imposed a fine of around $9,300 on the company.

Amnesty International has highlighted in its reports that in 1994, UCC abandoned the facility without carrying out a clean-up operation or dealing with the large number of stored chemicals, “leading to severe contamination of local water sources and soil.” “This has caused devastating and long-lasting damage to the health of the local population, and has been linked to chromosomal abnormalities similar to those diagnosed in people who were exposed to the initial gas leak,” the organization said.

In 2001, UCC was acquired by the U.S.-based Dow Chemical Company, which accepts no responsibility for the disaster or the contamination that remains at the site of the tragedy. The CEO of Union Carbide at the time of the disaster, Warren Anderson, died in 2014 without ever having been brought to justice, despite being charged and having been extradited by the Indian authorities. Neither Dow Chemical Company nor Union Carbide responded to a request for comment.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.