Mexico’s Gulf Cartel expands into US waters: Human smuggling, drug trafficking and illegal fishing

The latest wave of US sanctions reveals how the maritime border has become one of the most lucrative terrains for organized crime, which is negatively impacting the ecosystem and the survival of marine species

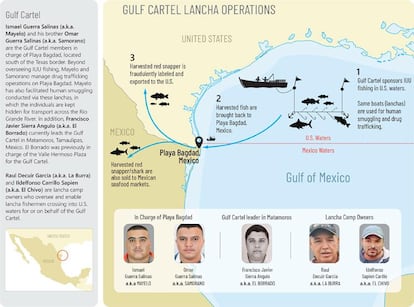

The sale of red snapper may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about the Gulf Cartel, but it has become one of the Mexican cartel’s most lucrative businesses. This was revealed by the latest round of sanctions from the U.S. Department of the Treasury, which on Tuesday added five individuals linked to the cartel to its so-called “black list.” These individuals are involved in a complex scheme that includes illegal fishing, human smuggling and drug trafficking. The illegal trade has not only heightened tensions along the maritime border between the U.S. and Mexico, but it has also taken a toll on the ecosystem and the survival of other species in the Gulf of Mexico. The region has become an expansive and highly profitable territory for the black market, while drug traffickers continue to boost their earnings.

“Today’s action highlights how transnational criminal organizations like the Gulf Cartel rely on a variety of illicit schemes like IUU [illegal, unreported, and unregulated] fishing to fund their operations,” reads the official statement. U.S. authorities consider the Gulf Cartel one of Mexico’s oldest and most dangerous criminal organizations, with its roots dating back to the 1930s. The cartel is based in the state of Tamaulipas, which shares approximately 230 miles of border with Texas. However, the cartel has increasingly focused its efforts on the Gulf, using it as a vast maritime corridor for trafficking drugs and people in small boats — around 10 meters long — that are designed to evade Coast Guard surveillance and quickly return to Mexican waters to avoid being caught.

The United States claims the Gulf Cartel uses these boats to engage in illegal fishing for red snapper, a prized species in the Gulf of Mexico that can fetch up to $60 per kilogram in American supermarkets. The cartel operates out of Playa Bagdad, using it as a base of operations for fishing expeditions in Texas waters, where restrictions are stricter and fish are more abundant. Authorities accuse the cartel of fraudulently packaging the red snapper as a Mexican product and exporting it back to the U.S., where payments are made in dollars and profit margins are higher. The Gulf Cartel is also accused of trafficking shark species, some of which are endangered, according to Washginton. “This activity earns millions a year for lancha camps. In addition, it also leads to the death of other marine species that are inadvertently caught,” said the U.S. Treasury statement.

At the top of the Treasury Department’s sanctions list are two brothers who are plaza bosses for the Gulf Cartel: Ismael “Mayelo” Guerra Salinas and Omar “Samorano” Guerra Salinas. “Beyond overseeing IUU fishing, Mayelo and Samorano manage drug trafficking operations on Playa Bagdad,” authorities said. Mayelo is also identified as an active human smuggler who uses boats to transport migrants across the Rio Grande, the natural border between Mexico and the United States.

Also named on the list is Francisco Javier Angulo, known as “El Borrado,” who controls the cartel’s operations in the border city of Matamoros, along with two individuals accused of running illegal piers: Raúl “La Burra” Decuir García and Ildefonso “El Chivo” Carrillo Sapien. Being placed on the sanctions list freezes their access to international banking systems and blocks any properties, companies, or vessels registered in their names.

The Gulf Cartel’s involvement in illegal fisheries has been under scrutiny for over a decade. As early as 2007, U.S. intelligence agencies had detected that the cartel was expanding its operations, venturing into the maritime border to capitalize on its dominance in that region. The scale of the operation has grown significantly. In 2010, there were just nine seizures of illicit fishing activities, according to official data. However, between 2020 and 2022, the number of intercepted boats surged to 321, according to the latest figures.

“IUU fishing and related harmful fishing practices are among the greatest threats to ocean health and are significant causes of global overfishing, contributing to the collapse or decline of fisheries that are critical to the economic growth, food systems, and ecosystems of numerous countries around the world,” the statement warns.

U.S. authorities have criticized Mexico for not implementing stricter measures to curb illegal red snapper fishing, issuing a negative certification against the country. This has led to restrictions on fish exports and the suspension of certain port privileges. The U.S. authorities also expressed frustration with Mexico, arguing that some fishermen have been apprehended as many as 40 times. On Monday, the U.S. Coast Guard announced the arrest of 19 Mexican fishermen and the seizure of nearly a ton of red snapper off the Texas coast. In late September, two other raids resulted in the arrest of nearly 30 Mexican fishermen from six different crews and the confiscation of more than 900 kilograms of red snapper in border waters. One video released by authorities shows the pursuit of the boat by both water and air before it was intercepted.

In August, three Republican senators, including Ted Cruz, introduced a bill aimed at identifying fish caught in U.S. waters and sold as Mexican using advanced technology and chemical markers that can trace the product’s true geographic origin. “Red snapper is one of the most well-managed and profitable fish in the Gulf of Mexico, but illegal fishing by Mexican lanchas puts law-abiding U.S. fishermen and seafood producers at a competitive disadvantage,” the bill sponsors argued. This time, the latest blow against illegal fishing has struck directly at the financial heart of the Gulf Cartel: illicit fishing.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.