Cannibals and devil worshippers: Russia’s delusional propaganda about Ukrainian troops

A leaflet distributed by the Russian Defense Ministry depicts Kyiv’s forces as depraved in the face of a model invading army

Russian Defence Ministry propagandists have a thing for bathtubs. This is one of many conclusions that can be drawn from a Russian government leaflet distributed in occupied Ukraine. The booklet, which consists of 28 illustrations, is entitled What’s the difference? There are two central drawings contrasting Russian and Ukrainian ideals: on the left, a Russian soldier, rifle in hand, walks with his wife and daughter; opposite them, two Ukrainian soldiers embrace in a bathtub, with hearts emanating, insinuating they are gay. In the other, a Russian soldier is submerged in holy water in the presence of an Orthodox priest; the Ukrainian soldier, on the other hand, is shown embracing Satan and a Nazi SS officer, again in a bathtub.

An officer from the Ukrainian 65th Mechanized Brigade provided EL PAÍS with the contents of this book last week. At least two copies were found in the belongings of Russian soldiers killed on the Zaporizhzhia front, according to this Ukrainian regiment. Russian media reported that the same booklet was distributed last spring in Russian schools.

The document also displays an obsession with teddy bears. In one of the images, under the slogan “The difference is...” a Russian soldier hands a teddy bear to a child, while his Ukrainian counterpart hands over the same toy, but containing an explosive device. In another, a Ukrainian soldier steals the toy from crying children. There is a page showing a Russian protecting a baby stroller during combat; the Ukrainian, on the other hand, uses it as a shield.

The leaflet contains scenes that may have a minimal connection to reality, and others that are pure delirium. In one, a Russian soldier kneels before a grave underneath a flag bearing an image of Christ; in front of him, a Ukrainian soldier kneels before a grave, but accompanied by a figure representing the devil, whose face is a Nazi swastika. In another, Russian troops patrol a village where harmony prevails, while the Ukrainians burn it down, waving Nazi flags while executing children.

Some of the situations depicted in the document draw attention because they are diametrically opposed to reality, contrasting the defense of the traditional family on the Russian side with the supposed degeneration of values on the Ukrainian side, placing particular emphasis on homosexuality. The truth is that Ukraine is a very conservative country and although homophobia is not a state policy as it is in Russia, it is a widespread problem in Ukrainian society. Kostia Andriiv, representative of the organization Gender Z, assured this newspaper last June that two and a half years of war have caused a setback of more than a decade in the rights of the LGBTQI+ community in Ukraine.

Echoes of the Great War

The interview with Andriiv took place a day after a march for LGBTQI+ rights in Kyiv, the first to be staged in the capital since the beginning of the Russian invasion. The demonstration was only able to advance 100 meters because homophobic groups halted it with threats of violence. “Wars, in any country, give wings to the extreme right, including in Ukraine,” Andriiv explained.

In Ukraine, the exact opposite of what the Russian propaganda aims to indicate is happening, but the Kremlin’s priority is to impress upon the more conservative elements of Ukrainian society that the country’s rapprochement with the European Union means the destruction of traditional values regarding family and religion. The EU flag appears in the book at an LGBTQI+ demonstration alongside Nazi emblems. The pamphlet also features numerous drawings of Ukrainian soldiers performing sacrilegious acts, such as urinating in cemeteries or burning churches.

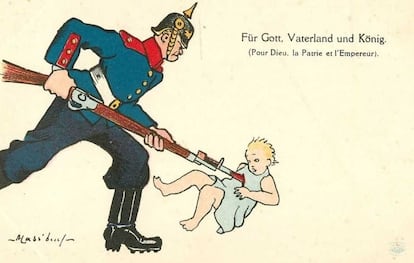

Pablo Sapag, a professor of the history of propaganda at the Complutense University of Madrid, explains that this pamphlet follows the decalogue of war propaganda established by the British War Office during World War I. These 10 rules have marked the development of these types of messages in all conflicts up to the present day, whether in audiovisual formats, social media, or on paper. “The only thing that would be different about a book like this from 100 years ago is the mention of homosexuality, because back then it wasn’t an issue.”

The rest, says Sapag, remains the same: the principle of linking the enemy with the devil; the contrast between good and evil; the idea of “transfusion,” which seeks to highlight the common historical past with the potential recipient of the document — in this case the population of eastern Ukraine, which is closer to Russian than European culture — in which the atrocities are committed not only against people, but also against that common heritage. Another tenet detectable in previous wars is that the Kremlin’s actions are “presented as a sacred cause, protected by the Orthodox Church.”

Adrián Huici, professor of the history of propaganda at the University of Seville, also notes that “these images are, in form, very similar to the cards and posters used above all by the French during the Great War, which were fundamentally the vehicle for the main propaganda strategy of the time, so-called ‘atrocity propaganda.’” One thing they have in common, adds Huici, is the depiction of atrocities committed against minors.

Prisoners of war

Another reality that Russian propaganda turns on its head is the treatment of prisoners of war. In one illustration in the booklet, two Russian medics carefully tend to a wounded Ukrainian soldier while a Ukrainian, a supposed torturer wearing an Azov Brigade emblem, is seen whipping a prisoner. In another, Ukrainians are depicted stabbing a POW.

The truth is that if there is any army in which prisoners of war are tortured “systematically and extensively,” it is Russia’s, according to the latest United Nations report on the subject, published on October 1. The photographs of soldiers in prisoner exchanges between Russia and Ukraine bear witness to this: emaciated and malnourished, the Ukrainian prisoners contrast with the better physical appearance of the liberated Russians. Since September, videos made public by Russian troops have also shown the alleged summary execution of around 20 Ukrainian soldiers taken prisoner in battle.

The backbone of the Kremlin’s propaganda to justify the invasion is its insistence on the so-called “Nazification” of Ukraine. This is laid out in the book, which reiterates the main objective of Russian propaganda, the Azov Brigade. This regiment and its political branch have their origins in far-right movements and maintain ultra-right elements and ideology that have spread since the start of the Donbas conflict in 2014. But between a country taken over by Nazis and reality, there is a big difference. This is the conclusion of Michael Colborne in From the Fires of War, one of the most comprehensive books ever published on the Azov movement. Colborne shows that Ukraine must face up to the problem of the far right, but that it is a common one in those countries that left the Soviet sphere, including Russia: “The history of the Azov movement is, in many ways, the history of all post-communist countries,” the author says.

Huici adds that the recurrent presence of Nazi officers in the propaganda images also responds to Moscow’s desire to claim that it is fighting against the enemy that has represented the greatest risk to the country in recent history. “To accentuate this drastic division between good and evil, Ukrainians are associated with one of Russia’s great enemies of the 20th century, the one that came closest to conquering and subduing the country.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.