Vicente Zambada: Another piece in the puzzle of the ‘El Mayo’ case in the US

The man who was once one of the heirs to the Sinaloa Cartel empire was freed from prison in 2021 after testifying against El Chapo in a plea deal

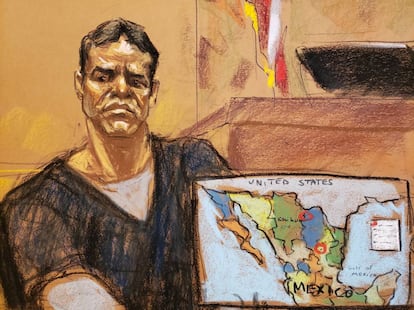

Few voices like Vicente Zambada Niebla’s have been as instrumental in helping the United States understand Mexican drug trafficking. “El Vicentillo,” as he is known, went from being one of the most powerful heirs to the Sinaloa Cartel to a key figure in the U.S. authorities’ account of the criminal structure. The name of Vicentillo, 49, is making headlines again now, 15 years after his capture in Mexico City and following the arrest of his father, Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, who has had his first brush with the U.S. justice system after being captured along with one of the sons of his former partner, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán.

El Mayo Zambada made his second court appearance in El Paso, Texas, last week. At the hearing, which lasted less than 10 minutes, Judge Kathleen Cardone asked the 76-year-old drug lord if he knew that his lawyer, Frank Perez, may have a conflict of interest. Perez is one of four attorneys who represented Vicentillo, who negotiated with the U.S. government and pleaded guilty to drug trafficking on April 3, 2013.

That day, Zambada Niebla admitted to organizing the trafficking of at least five kilos of cocaine and one kilo of heroin. The plea deal also required him not to resist U.S. authorities confiscating $1.373 million in assets, a fortune he illegally obtained by coordinating drug shipments to the United States for the empire run by his father and El Chapo from Sinaloa.

At that hearing in Chicago, Judge Ruben Castillo explained the fine print of the agreement to him. “Defendant agrees he will fully and truthfully cooperate in any matter in which he is called on to cooperate by a representative of the United States Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Illinois. This cooperation shall include providing complete and truthful information in any investigation and pre-trial preparation and complete and truthful testimony in any criminal, civil, or administrative proceeding,” the plea deal laid out.

By agreeing to those terms, Zambada Niebla avoided sitting in the dock at trial. The deal meant he avoided life in prison but faced a minimum sentence of 10 years. In May 2019, Judge Castillo sentenced him to 15 years for his role within the Sinaloa Cartel between 1996 and 2008. The sentence, however, would take into account the time Vicentillo had spent behind bars since he was extradited to the United States in February 2010. He spent some 700 hours in solitary confinement during which, according to his lawyers, he read some 400 books, learned to play the guitar, the piano, and even to paint.

“I think everyone deserves a second chance,” Vicentillo said on the day of his sentencing. “I have sacrificed a lot by leaving this life and taking my family out of the world they lived in. And I would do it again,” he stated, adding that he was sorry for “the bad decisions” he had made in his criminal life and asking for forgiveness from his children, his wife, and his mother.

Vicentillo avoided a trial through his plea deal but that didn’t keep him out of court. In fact, he was the star witness of another criminal proceeding. On January 3, 2019, Zambada Niebla entered the Brooklyn courtroom where the trial of the century was taking place. Inside the courtroom, he gave Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzman a smile.

In a couple of explosive days, Zambada Niebla, who was once one of the heirs to the Sinaloa Cartel empire, recounted the ins and outs of a criminal operation that spanned decades and reached countries such as Honduras, Belize, and even Brazil. He stated that his father even retained a budget of $1 million to cover bribes. On the payroll were Mexican army generals, who provided him with information about operations that could endanger the passage of drugs moving through the territory and heading for the border in cars, trains, planes, and even submarines.

“He didn’t want to testify in that trial,” said his attorney, Perez, in May 2019 at his client’s sentencing hearing. “He was worried about the consequences [...] but he told me he made the decision when he called the government because he no longer wanted to be part of this life. He did not want his family to have the same life he had.”

In his conversations with his attorney, Zambada Niebla admitted how hard it was for him to be part of the cartel. When he was 11 years old, he witnessed an attempt to kill his grandmother and his mother. That was just a foreshadowing of what was to come; the first attack he experienced firsthand was at the age of 16. “It was the first of many,” he told Perez. At that time, Zambada Niebla was moved by the fact that his firstborn had earned a degree in automobile design.

According to Perez, Vicentillo lives with the regret over his appearance at the El Chapo trial, where his father’s name was also mentioned frequently. “It was very hard for him to testify against his father. He struggled a lot because of that. Afterward, he listened to and read the articles that said a son had betrayed his father. To this day he struggles with this; it is a very difficult situation,” the attorney said in May 2019.

Vicentillo is now a free man. The U.S. Bureau of Prisons reported in April 2021 that the former cartel leader was no longer in the system. The court agreement indicates that the authorities will continue to monitor him for at least two more years. Zambada Niebla no longer owes anything to the U.S. Justice Department. Now it is El Mayo’s turn. Vicentillo can point his father the way to a reduced sentence.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.