La Unión Tepito, the Mexico City cartel that refuses to die

After the latest blows inflicted, the authorities claim the criminal organization has splintered and lost its power; independent researchers argue that it is a hidden monster with deep roots in working-class neighborhoods

It is a public holiday, one of those days in the long, warm Mexican spring that are reminiscent of the summer heat. Mexico City is marking the anniversary of Benito Juárez’s birth. People pour into the bars, the parks, the countryside. In a quesadilla restaurant at the foot of the Ajusco volcano, a family celebrates a child’s birthday. The police lie in wait: they believe they are witnessing a clandestine meeting of the leaders of La Unión Tepito, the cartel that has made the capital city its own through blood and extortion. Contrary to their information, however, it is not a criminal summit; it’s just a family picnic.

There is something strange, though. The police have been following the father of the birthday boy for months. He wears impeccable Carolina Herrera clothes. He only moves at dawn between Tepito, Polanco, Cuajimalpa, and other neighborhoods in Mexico City. He usually travels with an escort, but on this holiday Monday he lets his guard down and gives them the day off. The police believe he is the new leader of La Unión Tepito. They are not entirely sure, but in the Ajusco restaurant they see tattoos and some scars that leave no room for doubt. It is El Chori.

Eduardo Ramírez, alias El Chori, who intelligence reports place as the new leader of La Unión Tepito, is spending the day without his personal security detail in a recreational area in Ajusco. The police wait, patiently. There are too many people and they run the risk of a shootout involving civilian casualties. The family finishes eating, gets in the car and heads for Mexico City. The agents intervene at a point between the mountain and the Six Flags amusement park.

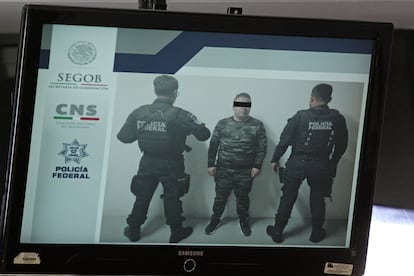

When they stop him, El Chori cries. A violent and feared man in the streets of the Tepito neighborhood, accused of murder and belonging to a criminal organization and suspected of disappearing his girlfriend, who no one has heard from since 2019. One of the most ruthless leaders of the Unión, according to a source close to the investigation, bursts into tears when the police catch up with him. He says they have the wrong man, that he imports sneakers from Panama, that he is just a businessman who abides by the law. The agents do not bat an eyelash. They have caught their prey.

Complicity since childhood

El Chori, according to the same source, is an extremely violent man who has made a name for himself through beatings, torture, murder, mutilation, and extortion. A repertoire far removed from that of a shoe merchant. In the huge Tepito market, the cartel’s stronghold, they fear him. When the organization sends him to collect an extortion payment, they are also sending a message: pay up, or you’ll be in trouble.

The authorities in Mexico City believe that La Unión is nowadays a splintered cartel, divided between independent factions and without a clear leadership structure. “Everyone wants to move up, they all feel they are leaders,” explains the source. Even so, they are still very dangerous, he says. Within six months, any of their leaders can move up the criminal ladder to a position of strength. The police’s strategy is to stop them before that happens, to cut off the heads that stand out in the organization. A few days after the arrest of El Chori last Saturday police arrested another Unión lieutenant, José Mauricio Hernández Gasca, alias El Tomate, one rung below El Chori in the group’s hierarchy.

In his 14 years as a crime reporter, journalist Antonio Nieto has covered more than 100 Unión-related deaths on the street. After more than a decade of investigation, in 2020 he published the most complete radiography that exists about La Unión. The reporter disagrees with the police: he believes that the official version of the splintering of the cartel is a “simplistic account.”

“It is a misinterpretation by the media and police agencies. It is true that the cartel has lost its level of organization: if you grip the strong parts of the same body, of course it hits the system. Like a sort of Al Qaeda or a terrorist organization, [La Unión] is divided into cells, but they are not in confrontation. I have never documented a single case in which these cells have wanted to kill each other for power,” says Nieto.

The journalist believes that the authorities tend to underestimate La Unión’s reach. In Nieto’s view, it is a full-fledged cartel, with connections to other criminal groups at the national and international level. Its strength, he explains, lies in a kind of primitive loyalty that outweighs power struggles. They are neighborhood friends who have grown up together and have each other’s backs: “They have had complicity since they were children; it is difficult for these ties to be broken.”

— And isn’t that also a simplistic story?

— Yes, but the point here is that the background they have makes them know their families, they know exactly where you stand, where your children are, your lover, your grandfather, your mother… on pain of being riddled with bullets. Although it sounds a bit like a movie, it is something that has been documented.

History of a union

In 2009, Pancho Cayagua brought together a group of young men from the neighborhood and created a kind of security company to protect businesses and customers in the Tepito market from extortion. Notorious hitman Édgar Valdez Villarreal, alias La Barbie, who had split from the Beltrán Leyva Cartel after the capture of kingpin Arturo Beltrán Leyva, tried to create his own organization in Tepito. The Cayagua kids prevented La Barbie’s designs. At first, they wore red T-shirts, a sort of homemade uniform, with the slogan “Unión Tepito.”

Shortly thereafter, Cayagua’s group, set up to protect the neighborhood from extortion, started forcing businesses to pay them for “security.” That’s when La Unión’s most profitable business began. They were no longer just kids from Tepito: Cayagua attracted corrupt police and federal agents who joined their ranks, an example of “everything that was wrong with the police,” summarizes the source. They became big, powerful, bloodthirsty, and diversified their business. In 2013, 13 young people were massacred in the Heavens nightclub, in the heart of the city. Another name began to circulate: El Betito.

In 2017, in one of the first major blows against La Unión, a rival organization rose up against Cayagua. Some 15 youths from the original group organized themselves and stepped forward. They called themselves the “little brothers,” or “the brotherhood,” Nieto says. As in the old Italian mafias, they were captains: a “horizontally structured” hierarchy in which only one name stood out above the rest, as the real boss: Roberto Moyado Esparza, alias El Betito.

A few years earlier, El Betito had been a street vendor and had a job looking after cars in the neighborhood, says the source familiar with the investigation. Nieto adds that he belonged to a gang that robbed armored cars and had a lengthy criminal record. Cayagua hired him and other youngsters to be La Unión’s hit squad. They become known for their brutality: murders, kidnappings, dismemberments.

After Cayagua’s death, El Betito stepped forward. In 2018, La Unión raised the stakes. One day in September, five hitmen disguised as mariachis burst into Garibaldi Square, the temple of popular music in Chiloé, and in six seconds they had gunned down 13 people. Six died. They were after the leader of a rival group, La Fuerza Anti-Unión. El Betito had been in jail for a few weeks, but few doubted that he was behind the massacre. He has been in federal prison ever since. For Nieto, he is the real capo of La Unión, despite being behind bars.

Nieto also does not believe that El Chori was the current leader, but rather Alberto Fuentes Castro, alias El Elvis. “The highest-ranking captain is Elvis, who was always higher than El Chori in the criminal world. There is not even a photograph of him: the photo that the Attorney General’s Office has distributed is false, that person is not him. You realize how much of a mafioso he is: 14 years have passed since the founding of La Unión Tepito and neither the media nor the authorities have a picture of him.”

Under El Betito, the cartel became fully involved in drug trafficking. It found a cocaine distributor in Colombia, which unloads the product in southeastern Mexico, but when the leader of that ring was arrested they lost their connection. Their main business is still extortion — between 4,000 and 5,000 pesos a week from each business, according to the source — but El Betito wants to expand, to cover the whole city: he goes to bars and nightclubs and “associates” with the owners: he puts one of his men in the bathroom, selling cocaine. If someone consumes drugs from another source, they are beaten. Police corruption aids them. Everyone profits.

Low profile, extortion, and neighborhood roots

They sell cocaine, but also what they describe as “boutique drugs”: hydroponic marijuana and Tutsi (a pink powder that becomes popular with wealthy consumers). Other organizations, such as the Sinaloa Cartel or the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), try to penetrate the city, but the Union is strong in its fiefdom. “An urban mafia behaves very differently than a group that is not primarily urban. When large groups like the CJNG or Sinaloa intrude into urban areas, they lower their profile. La Unión is imbued in the urban monster, it takes other criminal forms that allow it to consolidate its presence but not necessarily be visible,” says Rodrigo Peña, a researcher at the College of Mexico who is an expert in the criminal dynamics of the capital. Peña believes that La Unión Tepito remains the “most dominant” group in Mexico City.

Peña points to other factors that have helped La Unión to maintain its power: “The gentrification that has occurred in the [Tepito] neighborhood has to do with a different way of understanding the market, and the criminal group also participates in this: there is no more robbery, no more kidnapping, but we do know that extortion has increased.” For the researcher, extortion is the main resource of the Tepito gangs: “It is fundamental, it becomes a kind of political device: it allows them to mark their presence, build a group identity, consolidate an idea of territoriality that is usually very important for criminal groups, and gives them a relatively low profile.” In the capital, Peña recalls, there has been a “big drop in high-impact crimes (in the case of homicides that is the source of an important debate), but one of the few crimes that has risen is extortion.”

So, is La Unión a group in decline, as the authorities claim, or a monster in the shadows that still retains its strength? It may now be operating in its comfort zone but unfortunately for the authorities and the public there seems to be no end, no matter who they arrest. It is like a hydra: they cut off one head and another grows. “It does not seem that in the short term we can presume the end of La Unión,” Nieto concludes.

The journalist highlights another factor: many teenagers growing up in working-class neighborhoods like Morelos, Guerrero, or Santa María la Ribera aspire to join La Unión. “A piece of the neighborhood subculture in Mexico City is attached to this criminal group. This means they have a lot of cannon fodder; they have a lot of soldiers. It is very difficult for the authorities to uproot them.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.