Putin, the leader courted by the West, perpetuates the dictatorship of an increasingly bellicose Russia

The president, who came to power 24 years ago, is poised to win the presidential election for a fifth time, while his main opponents are in jail, exiled or dead

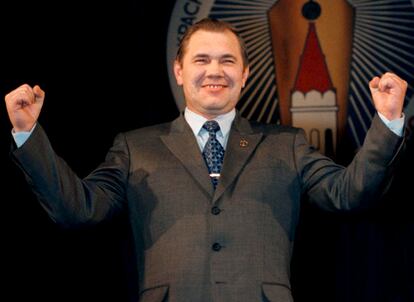

Vladimir Putin will win another Russian presidential election this Sunday. The agent of the former KGB — the Soviet Union’s espionage agency — will continue to hold the reins of the country until 2030. After Boris Yeltsin resigned 24 years ago in December 1999, Putin inherited a nation disorientated from the collapse of the USSR. He imposed his law with an iron fist, and for some, was considered the model to follow in the face of the supposed decline of democracies. It was a illusion. The supposed guarantor of stability, the president obsessed with making history, the man to whom the Russians gave immense power in exchange for peace, surprised his own people with the bloody invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The “operation” did not go according to the Kremlin’s plans. The conflict has now crept into Russian schools — where students will be taught how to throw grenades and how to shoot rifles — and is threatening to escalate into a war against the West.

On December 31, 1999, Yeltsin handed the presidency to Putin. At that point, Russia was a nuclear power in crisis, but with freedoms and hopes that previous generations had not enjoyed. One minute into his first address to the nation that New Year’s Eve, Putin declared: “I promise you that any attempts to act contrary to the Russian law and constitution will be cut short. The state will stand firm to protect the freedom of speech, the freedom of conscience, the freedom of the mass media, ownership rights, these fundamental elements of a civilized society.”

Barely six months later, Putin’s Prosecutor’s Office sent Vladimir Gusinsky — the owner of NTV, the only independent federal television in the country — into exile on accusations of tax evasion. NTV — which investigated the attacks that Putin as prime minister used to justify the second war in Chechnya in 1999 — was acquired by the Kremlin’s energy corporation, Gazprom. Its first decision was to shut down the political satire Kukly (Puppets) for joking about the president.

“There was no democracy in the classical sense then, but we had a great chance of achieving it,” laments Nikolay Rybakov, the leader of the Yabloko opposition party, in from his party’s headquarters in Moscow. His office is filled with hundreds of books, many of them about Soviet repression and the thousands of victims of the wars in Afghanistan and Chechnya in the 1980s and 1990s. Figures that today pale in comparison to the estimates of casualties in Ukraine.

“Many factors influenced this failure, both inside and outside Russia,” notes Rybakov. Many in the Russian opposition — not only Yabloko — think that more could have been done while there was still some margin for dissent. But it is also true that the Kremlin cracked down fiercely on opposing voices, and today it is as if the mass protests of the past decade never took place.

Rybakov maintains that there was “explicit support for Putin” in the West, pointing to Yeltsin’s self-coup in 1993 and the many deals the West made with the Kremlin oligarchy throughout these years. Even today, with the invasion of Ukraine, money still flows to both sides, recalls the opposition leader. “This path inevitably had to bring a person like Putin to power. He may have had a different surname, but their policy would have been the same,” Rybakov concludes.

Exiled, imprisoned or dead

The first man who could have defeated Putin decided not to run in the 2000 elections. This man was Alexander Lebed, the general who led the negotiations that ended the first Chechen war. He is known for saying: “Let me recruit a platoon of the children of the elite, and the war will be over in a day.” Described as “Napoleon” in the West, Lebed would die two years later in a helicopter crash. But in the opposition, there are doubts about the official version of the accident.

Lebed was Putin’s first great rival to disappear from the political scene. Over the years, several personalities critical of the Kremlin were publicly murdered: journalists from the newspaper Novaya Gazeta were killed violently, including reporter Anna Politkovskaya in her home in central Moscow in 2006; former KGB agent Alexander Litvinenko was poisoned with radioactive polonium in the United Kingdom in 2008; and former deputy prime minister Boris Nemtsov was shot in front of the Kremlin in 2015.

The most recent prominent figures to die in suspicious circumstances were opposition leader Alexei Navalny, who died in jail a month ago, and Yevgeny Prigozhin, the head of the mercenary Wagner Group, who was killed when his plane exploded two months after his failed uprising. Putin suggested his death — which has never officially clarified — may have been caused by intoxicated Wagner fighters letting off hand grenades, claiming that cocaine was found in the remains of the private jet.

All of these deaths occurred while Germany was building its Nord Stream gas pipeline to the Kremlin. In fact, Russia held the 2018 soccer World Cup just four years after the illegal annexation of Crimea and its military intervention in eastern Ukraine. Many political leaders attended the games, including French President Emmanuel Macron, who would be humiliated by Putin on February 7, 2022. When Macron traveled to Moscow in a desperate attempt to get the Russian president to stop the attack on Ukraine, Putin sat down with him on a six-meter-long table.

Ksenia Smolyakova, an analyst at the Riddle think tank, writes: “When we look back, it might seem that six years ago people in Russia lived in a different country.” On the street, there was euphoria that the World Cup had showed the world that Russia was an open and modern country. However, the Kremlin noticed that it was beginning to have problems. The government’s approval rating had sunk from 66% in 2014 to 33% in 2018, according to the Levada polling center, and Putin’s image was also worsening. “By the 2018 elections, the ‘Crimea effect’ of 2014 was already over,” says Smolyakova.

Similarly, the euphoria over Russia’s victory in the 2008 Georgia war gave way to the mass protests over electoral fraud in the 2011 Russian legislative elections, from which a new generation of opposition leaders emerged. Today, these figures are in jail, exiled or dead. “Authorities felt insecure,” says Smolyakova. “In 2020, there was an attempt to poison Alexey Navalny, followed by his arrest and the defeat of the regional network of his supporters.”

According to the Yabloko leader, the Kremlin has invented internal and external enemies to strengthen itself in power. “So people think that the problems cannot be solved. What bathrooms are we going to put in schools if they threaten to attack us? People think it is obvious that money should be spent on weapons,” says Rybakov.

Change everything so that nothing changes

Putin has remained in power for the past three decades, repeating two contradictory messages: on the one hand, he suggested that he would soon leave the Kremlin because no leader should rule forever, and on the other, he stated that he should stay in power for the good of the nation because he is indispensable.

“Seven years is too long. If you remain president for seven years, you can go crazy,” candidate Putin said in February 2004, 20 years ago, hinting that he would leave power after his second and final term.

Two decades later, last December, Putin leaked to soldiers that he would be standing for president for a fifth time. “He has told us that these are different, difficult times, but that at this moment he will be with the people and will run for office,” the soldiers said.

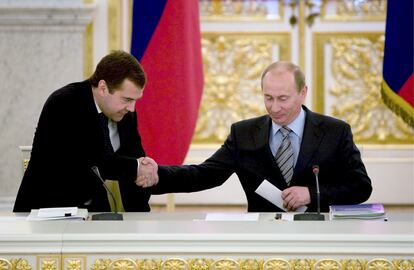

For 24 years, Putin has changed and interpreted the laws as he sees fit in order to remain in power. Due to the two-term limit established by the Russian Constitution, in 2008 he formed a tandem presidency with Dmitri Medvedev, who temporarily assumed the presidency that legislature. And instead of using the same ruse again in this year’s elections, he organized a constitutional referendum in 2020, in the middle of the pandemic, which reset his mandates to zero and will allow him to extend his reign until 2036.

With the presidency tightly in his grasp, each possible successor has faded into the background. A decade ago, the West considered Medvedev to be Putin’s liberal successor. Today the vice president of the Security Council has been relegated to making the biggest attacks against the West on Telegram — a closely fought competition among Russian politicians.

One of the best-positioned successors is Sergey Kiriyenko, first deputy chief of staff of the presidential administration and leader of the so-called “political bloc.” “His group has been responsible for building the regime’s pseudo-ideology,” says Andrey Pertsev, correspondent for the independent Russian media Meduza. “In addition, he has created the training network for bureaucrats, everyone will have some connection with him in the future, and he has known how to take advantage of the internet, his son was named head of VKontakte [Russia’s Facebook],” he adds.

Vladislav Surkov, Kiriyenko’s mentor at the head of the “political bloc,” equated Putin with Roman Emperor Augustus in a Financial Times interview in 2021: “He preserved the formal institutions of the republic — there was a senate, there was a tribune. But everyone reported to one person and obeyed him. Thus he married the wishes of the republicans who killed Caesar, and those of the common people who wanted a direct dictatorship.”

Attacks on the United States

One of the big reasons why a large part of Russians support the war against Ukraine is that it is seen as a way of standing up to NATO, in particular, the United States. This is not so much as to condemn U.S. invasions like the one in Iraq in 2003, but to put Russia on the same level as the United States and divide up its spheres of influence.

It wasn’t always like this. In 2000, Putin told then-NATO Secretary General George Robertson that he wanted to join the Atlantic Alliance, according to the latter. Similarly, after 9/11 Putin supported the U.S. campaign in Afghanistan. However, George W. Bush’s anti-missile shield and Russia’s own aggressiveness towards the former Soviet republics led Putin to deliver his famous Munich speech in 2007, where he accused Washington of establishing a unipolar international regime.

Those clashes — as well as the Kremlin’s rejection of globalization and some human rights — shaped state ideology over time. Last year, it reached a point where Putin enshrined in his foreign policy documents that Russia is “a unique country-civilization” that opposes the United States.

There are different interpretations about Putin’s motives for invading Ukraine. According to Intigam Mamedov, an expert on Eastern Europe and researcher at Northumbria University, the attack was due to a combination of factors, including two important elements. On the one hand, the transition of power in international relations. “Russia, as a power dissatisfied with its position, is trying to take advantage of every opportunity to increase its power against the dominant power [the United States],” says Mamedov. On the other hand, “the narrative of a clash of civilizations in Russia is being pushed. It is no longer a small military operation, as in February 2022, but rather a confrontation to protect one’s identity,” adds the expert.

Stalin's veneration

“After the special military operation, socialism!” proclaims a pamphlet from the Russian Communist Party. Loyal to the Kremlin, it assures that Putin is doing “a good job” and has restored old traditions such as “the Stalinist parades of athletes in the Red Square.”

“There was no de-Stalinization,” laments Rybakov. “The fact that the state did not reflect on Stalin’s regime of terror has contributed enormously to the current situation. If you can kill thousands of citizens, what is not allowed?”

Oleg Lukin, a researcher at Diachrony and analyst for the media The World Order, states by phone that the Kremlin “has not only reinterpreted history, but also takes over the symbols and establishes what and how each ritual should be, to separate those it considers ‘its own’ from those that are suspected of siding with the West, of being Russophobes.”

However, Lukin considers that the current repression is “a sign of the Kremlin’s weakness” in the face of a large sector of the population that is dissatisfied.

Another sign of the USSR’s influence is the return to puritanism. If in Soviet times, the phrase “There is no sex in the Soviet Union” went viral thanks to a TV show in 1986, in Putin’s Russia of today, the same taboo is covering more and more spheres of private life.

A few days ago, a professor at a Volgograd University was fired for sending a video of his cacti to his colleagues. Someone in charge saw phallic figures in the images, and the professor was immediately fired. It might seem like an anecdote if it were not preceded by many other incidents of “misbehavior.” Since photos of Russian elite in their underwear at a party in Moscow were leaked in December, the police have carried out several raids on private parties.

Political scientist Tatiana Stanovaya warns: “The case of cacti is very striking. It shows that it is no longer just a matter of authorities rejecting ‘non-traditional values,’ but of everything that is considered depravity. This issue already affects a much broader sector of the population,” she explains.

In Putin’s heavily policed Russia, what people do in private has become a matter of state.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.