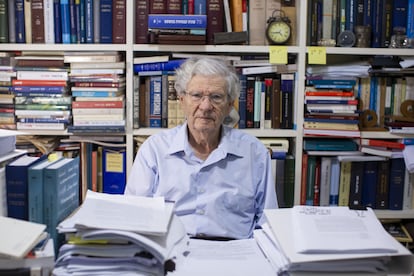

Israel entrusts defense against genocide charges to its most prestigious judge, a Netanyahu critic and Holocaust survivor

Aharon Barak, 87, is to present his country’s position on Friday to counter accusations brought by South Africa before the International Court of Justice

The house in Tel Aviv that retired judge Aharon Barak left this week at the age of 87 to represent Israel at the hearings in The Hague is the same one that he was unable to leave just a few months ago, when dozens of supporters of the judicial reform promoted by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu — the same government leader who has now approved his appointment — routinely surrounded the home waving banners that called Barak a “dictator” or “head of the snake” for his role in the Supreme Court for 28 years (1978-2006), the last 11 of which he served as its president.

Those protests took place prior to the Hamas attack of October 7, at a time of deep social and political divisions over the controversial reform. Already retired and in his eighties, the judge ended up becoming a symbol, despite not wanting to. For the political right, he represented a secular elite of European origin who exploited his position to boycott the results of the polls. For the liberals who took to the streets for months, the separation of powers was in danger, so they also surrounded his house, but to thank him and to sing the national anthem.

Today, all of them are united in their support for the war in Gaza. And the same Netanyahu who was criticized by Barak is the one who approved his appointment to represent the country before the United Nations’ International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, in a “display of how seriously Israel is taking the case,” says Amijai Cohen, PhD in Law from Yale University and researcher at the Israel Democracy Institute research center.

On Thursday, at the beginning of the hearing, South Africa asked the court for precautionary measures to make Israel suspend its military campaign in Gaza and requested the opening of proceedings for violation of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948). The suit includes statements — from the president of Israel to musicians, as well as several ministers and military leaders — that, in the opinion of South African lawyers presenting their case, show genocidal intent and promote it. Barak will present Israel’s position on Friday.

Barak’s appointment was widely applauded in the country, except by the most radical members of government. The Minister of Finance, Bezalel Smotrich, described it as a mistaken decision taken behind his back, while Heritage Minister Amihai Ben-Eliyahu, also a far-right politician, questioned whether Barak had the “correct notions on the subject.” One of the architects of the judicial reform, chair of the Knesset’s Constitution, Law and Justice Committee, Simcha Rothman, bit his tongue. “My silence is thunderous,” he wrote on social media. Not so Tally Gotlib, a Likud lawmaker who accused Netanyahu of “humiliating the right” with the decision and of “detesting the voters” of the party to which they both belong.

Unity

The appointment has several symbolic elements to it. One is to bring to The Hague the most important judge in Israel’s 75-year history, famous for his interpretive legal approach and his judicial activism. He was the first to determine in a ruling the right of the Supreme Court to annul any rule that conflicts with any of the 13 basic laws by which Israel is guided in the absence of a Constitution. He himself knocked down 20 of them. Added to this is his legal prestige abroad. He has an honorary doctorate from renowned universities such as Yale and Oxford.

And then there is the message of national unity against the world inherent in sending a figure who has been critical of Netanyahu. “He is probably the greatest jurist in the history of the country. And the attacks [from the right] this year have only reinforced his status in the world, as someone who stands up to the government,” Cohen said in a telephone interview. This expert also believes that the decisions in The Hague navigate “halfway” between politics and the purely legal, so the appointment “sends a message” of moving the field to the latter. “The political decision would have been to choose another candidate,” he adds. In a WhatsApp group shared by members of the government, Interior Minister Moshe Arbel considered that the choice was “very reasonable, particularly for the international scene,” according to national public television.

Barak’s biography adds another symbolic element. The jurist who will defend Israel on Friday against the accusation of genocide survived one as a child. A farmer concealed him in a shipment of potatoes and took him out of the ghetto of Kaunas, his hometown, where the Nazis imprisoned the Jews after invading Lithuania.

He arrived with his family in Palestine in 1947, a year before the creation of the State of Israel. In the 1970s, already as legal advisor to the government, he forced the fall of Yitzhak Rabin’s first executive because his wife, Leah, had an account in dollars, something that was prohibited at that time. When Likud, the right-wing party currently chaired by Netanyahu, ended three decades of Labor hegemony, he retained his position. The prime minister, Menachem Begin, included him in the negotiating team for the peace agreement with Egypt of 1978. On a shelf in his office he has a photo of that moment, which shows the former president of the United States, Jimmy Carter, whom Barak calls “my good friend.”

Another paradox of his life is that he was presiding over the Supreme Court when the same UN International Court of Justice declared illegal in 2004, in a non-binding opinion, the separation wall that Israel had begun to build in the West Bank. Barak, who presided over the Israeli Supreme Court throughout the Second Intifada (2000-2005), gave the green light to the barrier, ordering only some variations in the layout. Also to selective assassinations, restricting them to causing “proportionate” damage.

The small Israeli anti-occupation left has always seen him as the friendly face of an oppressive system. The president of the executive committee of the human rights group B’Tselem, Orly Noy, recently lamented that he has put on “the mantle of Dr. Jekyll to once again legitimize the crimes of Mr. Hyde [Israel].”

In an interview with this newspaper in May, when he was on everyone’s lips due to the judicial reform, Barak said that his career as a judge had been marked by the “search for balance” between two lessons he learned from living through Nazi persecution: the “importance” of the existence of the State of Israel — “if we [Jews] had had a State in 1941 or 1939, there would have been a Holocaust, but in a different way,” he said — and the value of human rights, because “the “ghetto is the tyranny of unlimited power.” On Wednesday he apologized on the phone for not being able to grant another interview, given his new assignment.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.