Venezuela and its territory, a national trauma

The country has lost more than 500,000 kilometers since its foundation in international rulings or as a consequence of an erratic diplomatic strategy

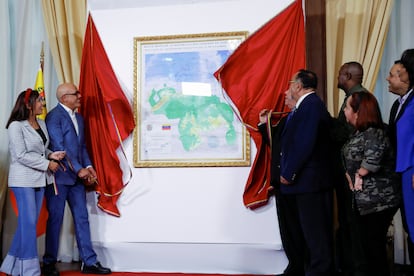

The sharp increase in the nationalist discourse in the cause of Venezuelan sovereignty in Guyana Esequiba, promoted with unusual aggressiveness by the Government of Nicolás Maduro, rests on a conclusion that has been dormant for years, but that underlies the psyche of society, starting with the Armed Forces: the large amount of legitimate territory that the nation has lost in various international rulings and confusing political circumstances, in the times of the Spanish colony and also as an independent nation.

In spite of this reality and the enormous propaganda campaign orchestrated by the national government to promote a referendum on the annexation of the Essequibo, the voting centers were sparsely populated throughout the day and Chavismo did not obtain the turnout it would have wished to capitalize on the sovereignty initiative.

The event, on the other hand, has given way to the debut of a very intransigent nationalist tone in the high Government, which is serving as an argument to judicially penalize any uncomfortable political position. Four of the closest collaborators of the opposition candidate, María Corina Machado -a traditional activist in the cause of the Essequibo, but who is now appealing to the International Court of Justice to settle her sovereignty-, have been arrested, accused of collaborating with the multinational Exxon Mobil and the Government of Guyana.

The former Captaincy General of Venezuela, created in 1777, had about 1,500,000 square kilometers (the current Republic of Venezuela has 912,000), which included the island of Trinidad, one of the provinces of that entity, seized by the English from Spain in 1802. With the advent of independence, the country also lost control of the Guajira peninsula, part of the current Colombian eastern plains and large sectors of the Amazon, to the benefit of Colombia and Brazil.

Also, progressively, the Guyana Esequiba. A territory over which there has been a long diplomatic struggle, first with the British, who encouraged the colonization of the area, and then with the independent Government of Guyana. An issue that had remained dormant as a controversy for several decades until now.

“There are two ruling that have left a deep mark on Venezuela’s territorial identity,” says Lauren Caballero, internationalist and analyst at the Central University of Venezuela. “The 1891 ruling, which defined the definitive border between Venezuela and Colombia and the almost total loss of the La Guajira peninsula, and the Paris Arbitral Award of 1899, which resulted in the loss of the Essequibo. These two events have somehow generated a kind of trauma in the conscience of generations of Venezuelans, to the point that diplomacy in Caracas avoided during almost the entire 20th century to commit itself to any international treaty that would oblige it to settle its territorial delimitation with third parties”.

The famous “landmark of Castilletes”, after the delimitation that resulted in the loss of almost the entire La Guajira peninsula, is the starting point of the famous dispute over the Gulf of Venezuela - controlled by Venezuela, but claimed in part by Colombia - which for years was the one that monopolized all the news headlines in those years, with some peaks of diplomatic and military binational tension included.

“Following the doctrine of Simón Bolívar, Venezuela always appealed to the principle of uti posedetis juris to amicably and expeditiously delimit its borders after the dissolution of Gran Colombia. By that time, the first British colonists were already beginning to cross the border on the western bank of the Esequibo River, which provoked diplomatic protests from Bolivar himself”, explains Kenneth Ramirez, president of the Venezuelan Council of International Relations.

Both experts warn that the loss of these territories was also due to the incipient diplomacy of independent Venezuela and the difficulties of effectively controlling all its territory at the time. Venezuela was, moreover, one of the various theaters of operations of British imperial diplomacy throughout the world.

“With Brazil, the country also lost thousands of square kilometers,” says Ramírez. “Inexplicably, Venezuela accepted without major opposition to depart from the Uti Posedetis Juris, and the 1859 treaty of limits confirmed Venezuelan rights over the basins of the Orinoco and Esequibo rivers”. In that year, one of the most chaotic years in Venezuela’s history, a nation without a government, the Federal War began, a four-year civil conflict, even more virulent than the war of independence.

The Venezuelan Congress had not wanted to ratify the famous Pombo-Michelena treaty, which placed satisfactory limits to the Venezuelan claims against Colombia in 1833. After successive Colombian-Venezuelan negotiations without agreements, “in 1886, the Paris Act appoints Queen Maria Cristina as arbitrator of right to execute sentence in this dispute with Colombia. The 1891 Award is very detrimental to Venezuela, since it takes away extensive territorial zones from the Caribbean to the Amazon”, says Ramirez.

“This is what explains the reluctance of the Venezuelan State to go to the International Court of Justice to settle the Essequibo dispute with Guyana, this has been a permanent position”, states Caballero. “In spite of the fact that in the Geneva Agreement of 1966 the Venezuelan negotiators did not exclude the possibility of a judicial settlement, as stipulated by the United Nations”.

“Venezuela has lost a fifth of its territory since the times of the Captaincy General,” adds Kenneth Ramírez. “As the poet Andrés Eloy Blanco rightly stated in a famous parliamentary speech in 1941, it did so without firing a single shot. It is natural that there is a sensitivity to the issue of borders. And it has been, once again, the diplomatic mistakes of the Maduro government that have us in this situation, refusing to attend the International Court of Justice”.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.