Pacts, conspiracies and betrayals: The best-loved restaurants of politicians and elites from Paris to Bogotá

Travel the world to the cafés and eateries where history is made and secrets shared over fine wine and hors d’oeuvres

Some of the best-known restaurants in the world have been more important to a country’s politics than its gastronomy — establishments where the ruling class dines with discretion, or risks precisely the opposite. From Paris to Buenos Aires to London, these restaurants have welcomed guests ranging from paramilitary assassins to ousted politicians and newly elected presidents. Pacts have been signed and coalitions broken over their fine linen tablecloths. For some powerful patrons, their most-loved place serves as a kind of talisman or second office, with the added benefit of serving excellent food.

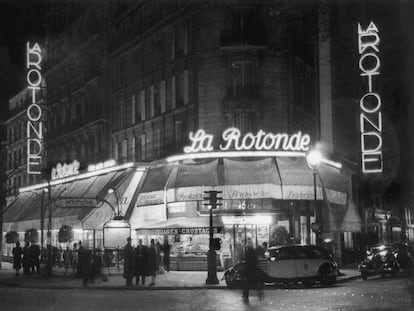

Paris: La Rotonde — A symbol of Macronism with an intellectual edge

The brasserie La Rotonde, like other restaurants of its kind in Paris, is more than just a place where guests dine on seafood and onion soup, sole meunière and steak tartare. In recent years, during the presidency of Emmanuel Macron, it has become a symbol of the French leader and the turmoil surrounding his mandate.

One could say, at least unofficially, that the president was inaugurated right there, behind the gleaming windows and red awning that constitute the façade of this comfortable café, less ostentatious than Fouquet’s, the favorite of another French president, Nicolas Sarkozy.

It was at La Rotonde, on April 23, 2017, where Macron was joined by campaign staff and friends to celebrate qualifying for the presidential runoffs. And ever since, the restaurant has served as the president’s preferred venue, frequented both privately and with esteemed guests, such as German Chancellor Olaf Scholz.

The brasserie’s public association with Macron has caused it to come under fire on more than one occasion. The Yellow Vests and pension reform protestors saw the place as a symbol of the president, and attacked it as such. But the restaurant’s history and symbolism long predate today’s political landscape.

La Rotonde, located on the corner of Montparnasse and Raspail Boulevards, was a frequent haunt for the writers of the Lost Generation and the bohemians of Montparnasse, as well as Spain’s exiles in the 1920s, an era when, every day, between 1:00 and 3:30 in the afternoon, famous Spaniards including Miguel de Unamuno would gather at the café, sitting in the back, next to a window overlooking Boulevard Raspail.

After World War II it became an important gathering place for existentialists. In her memoirs, Simone de Beauvoir, who actually grew up in a flat above La Rotonde, recounts how she first got drunk in the restaurant downstairs.

Buenos Aires: La Biela, pilots, police officers and writers

In Buenos Aires, Argentina, on the corner of Juncal and Quintana, some 100 meters from the Recoleta Cemetery and right next to a towering ombú evergreen — planted sometimes around the end of the 18th century and believed to be the oldest tree in the city — is a restaurant known as La Biela.

It was founded in 1850 under the name La Veredita, in a neighborhood known for its knifings, prostitutes and thieves. A few years later, due to its popularity among members of the Argentine Civil Pilots Association, it changed its name to Aerobar. Politicians of every tendency would pass through its doors. Over time, the neighborhood has changed and so have the premises. Around 1940, when car races were all the rage in Argentina, it assumed its present name (“la biela” is the word in Spanish for the rod that connects a piston to a crankshaft) and the place soon became a favored meeting spot for lovers of the sport. One of the café’s regulars was the five-time Formula One champion, Juan Manuel Fangio.

During the civic-military dictatorship, members of the Alianza Anticomunista Argentina (AAA), an ultra-right-wing parapolice gang, frequented the restaurant as well: Ramón Camps, chief of the Buenos Aires Police Department, often ate lunch at La Biela, and in 1975, the Montoneros guerrilla resistance group designated the café as a “target site in oligarchic areas” and organized an attack that started a fire, but left no victims.

Writers Adolfo Bioy Casares and Silvina Ocampo lived right around the corner, in an apartment on Posadas. Bioy used to eat lunch in one of the restaurant’s dining rooms and would reserve table 20 for coffee with his guests, which included none other than Jorge Luis Borges. Today, in the café beloved by politicians, artists, intelligence agents and journalists alike, table 20 is still unavailable: it is occupied by two sculptures of the famous writers made by Argentine artist Fernando Pugliese.

Brasília: The Piantella, democracy’s memory

When El Piantella opened its doors in 1979 in Brasília, the city was about to complete two decades as the futuristic capital of a country that was still a dictatorship. In Brazilian distances, the restaurant was located just around the corner from the offices of the three branches of government and the national ministries, and so it soon became a favorite meeting place for the opposition to the dictatorship, whose members would gather every day to eat lunch and dinner and to stay up drinking until the place closed at dawn, enjoying a refined menu and live piano music.

For four decades, El Piantella was the favored meeting place for Brazil’s politicians, and often the backdrop to signing agreements and settling on compromises. Its lounges and private rooms embodied the ups and downs of the political class during those first glorious years after the fall of the dictatorship, when politicians of various stripes joined forces to rebuild Brazilian democracy and mingle on one of the restaurant’s two floors, along with journalists who came fishing for news.

The reigning favorite on the menu: filé a la Muscovite, a sirloin steak in cream sauce, flambéed with vodka and topped with a teaspoon of caviar.

It was also at El Piantella that the pro-democracy movement known as Diretas Já was originally conceived in the mid-eighties — a coalition that would grow to eventually cook up the country’s 1988 Constitution.

When Lula made history in 2002 as the country’s first working-class president and received his corresponding certificate, he invited a group of close friends to El Piantella to celebrate earning his first “diploma,” because he had never finished school.

The restaurant closed its doors on August 31, 2016, the day Brazil’s senate impeached the first female president in the country’s history, Dilma Rousseff. It was a mortal blow. A new owner tried to resurrect it, but the pandemic put an end to that plan as well.

Washington D.C.: Cafe Milano, the “second White House cafeteria”

Cafe Milano opened its doors the same day Bill Clinton was elected president, in November 1992. This Italian restaurant in Georgetown has since become a favorite destination for Washington elites. Although dozens of restaurants in the District of Columbia have had the occasional president as a customer, and make sure to brag about it, Cafe Milano is probably the most frequented by presidents and other members of government: congressmen, heads of state and foreign leaders, not to mention Hollywood stars passing through town and other major media figures. In a country as polarized as the U.S., it is notable that the restaurant still attracts Democrats and Republicans alike.

The food isn’t memorable and the prices aren’t cheap: with taxes and tips, pastas and pizzas run about $40, fish is over $50 and meat dishes can cost close to $80. Nevertheless, the restaurant’s Italian owner, Franco Nuschese, has managed to turn Café Milano into one of the capital’s most important spots.

Bill Clinton is a regular, and Barack Obama and Joe Biden have visited as well. There are no records of Trump having eaten there, but several members of his cabinet were regulars. One night, the former president’s secretaries of state, treasury and commerce wound up dining there at the same time, at separate tables, earning Cafe Milano the nickname, “the second White House cafeteria.” Clinton had eaten there that same day, as had Fox host Bret Baier. The Queen of Thailand had the place closed down for a private celebration; she brought her own silverware. And Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie happened to go there the same day as Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones.

When it first opened, Cafe Milano had enough tables to seat 52 diners. Now it has 300 seats and an extended schedule: reservations are booked months in advance, so it’s not that difficult to secure a table in the main dining room or on the terrace, and join in the exclusive atmosphere.

Bogotá: Pajares Salinas, a taste of conspiracy

At Pajares Salinas, apart from eating and dining well, one conspires deliciously, a Colombian columnist once quipped. The most powerful people in Colombia can be found enjoying this eclectic, low-lit restaurant in northern Bogotá. The richest businessmen and the most powerful political elites — the true patricians of our modern world — have reclined on its plush seats. Presidents have paraded through its doors one by one — save for Álvaro Uribe, who resisted its spell. The parking at the entrance is lined with high-end vehicles and chauffeurs patiently await their lords. At the entrance, four maitres greet you to find your reservation — getting a table on short notice is no easy task — and then lead you to an open-air table: everything in the place is in out in the open; no one can hide.

The aisles are lined with coolers filled with wine and champagne. The tables, perfectly balanced, are decorated with small vases of carnations. The menu is of Spanish origin, with a slight French twist. A dim light casually illuminates the dark corners, an example of one of the main attractions of the place, where cell phone service is scarce: you don’t know if it’s day or night. Lunches blend into dinners that turn into a night out at the elegant second-floor bar, where classic armchairs in fashion fifty years ago are complemented by the original library of the restaurant’s founder, Saturnino Salinas Pajares, a Spaniard who arrived in Colombia in the 1950s with nothing but a suitcase, a book of recipes entitled La nueva cocina elegante española, and a chef’s jacket. The waiters, perfectly uniformed, overhear confessions that will show up later on the evening news, but discretion is the rule of the game, and their ears and lips are sealed. On any given day you might hear a guest (yelling, because people tend to come to Pajares Salinas to be seen) closing a $100,000 deal over the phone — an insignificant amount in the eyes of others who might be in the room like the banker Gabriel Gilinsky or billionaire Luis Carlos Sarmiento Angulo.

Colombia’s current president, Gustavo Petro, made a few appearances during his campaign, but the first lady, Veronica Alcocer, has been a more consistent guest, often arriving with her clique of Spanish advisors. Pajares Salinas is known as a place where you can get a bit tipsy, but always within the limits of good taste. And if someone pushes past those limits, three chauffeurs wait on-site to drive the incapacitated back to their elegant homes, put on their pajamas and kiss them goodnight.

St. Petersburg: Stáraya Tamozhnia, the Wagner Group’s go-to spot

The Old Customs House restaurant (Stáraya Tamozhnia, in Russian) is where the leader of the Wagner Group, Yevgueni Prigozhin, got his start. The establishment, founded in 1996 in the heart of St. Petersburg, on Vasilievsky Island, across from the Winter Palace, is where Prigozhin, who died in August in an unsolved plane crash two months after his failed rebellion, first began weaving his network and meeting with Russia’s political elites. Among them: St. Petersburg’s own Vladimir Putin, at the time the right-hand man of the city’s mayor.

The restaurant, as its name suggests, is located in an old 18th century customs house, and this history inspires its decor, which goes so far as to feature mannequins of Tsarist officials. But look past the place’s peculiar style and you’ll find one of the most refined establishments in Russia’s “cultural capital.” Its menu focuses on Russian gastronomy, along with some European derivations of those original dishes. Specialties include: cabbage soup with sauerkraut and veal, stewed veal with mashed potatoes, and “delicate pancakes with salmon and red caviar.”

The menu prices are high compared to other restaurants in the city, but reasonable considering the restaurant’s fame, its central location, and the fact that its tables host some of the country’s most powerful elites. A main course costs between 900 and 1,000 rubles — ten or eleven dollars at the current exchange rate — and any of the exquisite Slavic soups run half that. As for the wine list, its selection is as diverse as any other Russian establishment’s, which are all limited by the sanctions. Their Spanish offering, a 2017 Castillo de Albay rioja crianza, costs 500 rubles, or about five and a half dollars.

The restaurant made famous by Russia’s top mercenary has four rooms, one of them for VIP clients and another for wine tasting. Rooms in the restaurant can also be reserved for weddings and other private events.

London: The Cinnamon Club, the spice of Westminster

For decades, the height of sophistication for the British palate was a good curry — “curry” being the generic name given to any dish of Indian origin or inspiration with a spicy sauce. It became as much of a national dish as fish & chips or Yorkshire pudding. And Westminster MPs were no strangers to the exotic. The rules of the game changed in 2001, when renowned chef Vivek Singh opened The Cinnamon Club.

Just a five-minute walk separates the British Parliament from the old Westminster Library on Great Smith Street: a wonderful red brick building with Victorian architecture that now houses the restaurant, which is frequented by members of the House of Commons and ministers of Her Majesty’s Government. At any time of day, the tables, which are surrounded by wonderful hardwood-paneled bookcases featuring a vast collection of exquisitely arranged titles, seat politicians and journalists and ministers and deputies, in an atmosphere that mixes work with fraternization, and plots and conspiracies, of course.

Like the idea for curry itself, Vivek Singh mixes Indian cuisine’s most traditional elements with the Western recipes recognized and beloved by his clientele, and has given the place an air of functional elegance to suit the tastes of the politicians who come to London and Westminster, the center of power in the United Kingdom, and think they are walking on clouds.

Rishi Sunak, the first U.K. leader in history to have Indian origins and be a practicing Hindu, chose The Cinnamon Club to host more than 70 volunteers who came to support his campaign for leader of the Conservative Party. He lost to Liz Truss, but two months later, she resigned, and Sunak was chosen as the new prime minister.

Barcelona: Ca l’Isidre, politics through the side door

If the walls of Ca l’Isidre’s private dining room could talk, its secrets would be enough to fill a multi-season political series, where agreements, dialogues, disputes and confrontations are resolved over fine food and wine. With a refined sense of discretion, this restaurant that features modern Catalan cuisine, located next to the Paral-lel metro station, has fed Catalonia’s political class throughout its entire history, which now spans more than half a century. The restaurant was founded by Isidre Gironès and his wife, Montserrat Salvó, but is now run by their daughter, Núria Gironès, who commands the elegant dining room — a private space with a singular atmosphere, where white tablecloths are perfectly ironed and fresh flowers are always front and center.

In addition to a stylish dining room, which shuns trends in favor of imbuing its unique personality into each and every detail, Ca l’Isidre has a private room with capacity for 14 people, who can access it through a side door without being seen by other customers. Politicians of all stripes have used this clandestine entrance to meet with accomplices or rivals in a neutral space and avoid potential eavesdroppers. Occupied several times a week by two, three or four politicians at a time, it has also served as the scene for more festive meetings: parties that fill the room to capacity.

There are those who still remember the day Ca l’Isidre threw discretion out the window, when a blue Mercedes pulled up to its front doors. It was the eighties, and King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofia were on an official visit to Catalonia, planned to coincide with their May 14 wedding date. Spanish power couple Jordi Pujol and Marta Ferrusola joined them in celebration, and chose Ca l’Isidre for the occasion. Years later, more than one decisive meeting held in Ca l’Isidre’s coveted private room and featuring Pasqual Maragall and Joan Antoni Samaranch would result in Barcelona hosting the Olympic Games.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.