The life and death of Ito, the hitman who assassinated a presidential candidate in Ecuador

Poverty, exclusion and violence: this is the story behind Johan David Castillo and the other assassins who were hired to kill Fernando Villavicencio

That day, he woke up late. The sun was already scorching the red bricks of a two-story house on the outskirts of Cali, Colombia. The air inside was suffocating. On the wall, he saw the picture of red roses that he had drawn for his mother — “Mom, I love you” — and the one of the characters from Looney Toons that he had painted for his son: “I love you, Liam David.”

He wasn’t very tall. He had short hair, a dark complexion and small, hard eyes. He washed his face, ate breakfast and dressed in the wrinkled clothes that he kept in a plastic bag. The change of clothes that he put in his backpack was the only indication that he was going on a trip.

It was a few minutes before noon when he ran into his grandmother:

“May the Lord bless you, papi. Where are you going?”

“I’m off, I’ll be back in no time,” he answered, making no attempt to be precise.

The boy decisively crossed the threshold of the door and went down the spiral stairs that led to the sidewalk. He had to go kill a man.

Johan David Castillo López — alias “Ito” — was the 18-year-old Colombian hitman who murdered Ecuadorian presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio on August 9, along with four other gunmen. In a video, Villavicencio is seen getting into his truck after a rally, surrounded by his bodyguards. In a fraction of a second, in front of the vehicle, Ito appears like a shadow, dressed in jeans, a loose white T-shirt and a cap over his head. No one notices him until he pulls out a gun and starts shooting. Ito flees in the middle of the road, until he’s shot by one of the politician’s bodyguards. He falls and, a few seconds later, a police officer arrives and begins to kick him, in an attempt to take his weapon away. Ito tries to get up and run, but collapses again. He is seriously injured. Another officer takes him by the arms and drags him to the sidewalk.

There are other versions to this story. In one, the hitman is shot twice and a crowd of people — who have just realized what has happened, after a few moments of confusion — beat him until he is close to death. In another version — as explained by the authorities — Ito received nine shots that immediately killed him. In any case, five minutes earlier, he had completed the job that made him travel by road from Colombia to Ecuador.

His family received the coffin with his body seven days later, on August 16. They themselves paid for the repatriation, with the help of contributions from family and friends. They buried him in the Central Cemetery of Cali — a labyrinth of tombs and pantheons, where it’s not easy to find your way. They didn’t engrave any message on the marble. Instead, they wrote his name by hand on a piece of cardboard, placing it over the grave.

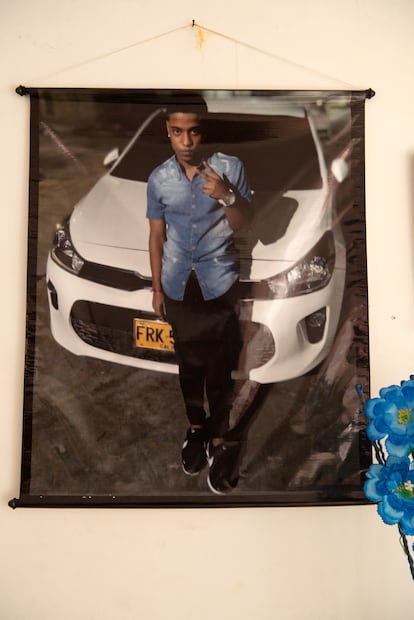

In Ito’s family home, in the Lagunas neighborhood of Cali, an almost life-sized photo of him presides over the living room. The teen — who was about to turn 19 — poses, making the victory sign. He’s wearing a big watch, a denim shirt and black pants. He leans on the hood of a white car that looks like his, even though it wasn’t. He saw it parked on the street and he liked it. Ito had neither a car, nor a motorcycle. He used his brother-in-law’s bicycle. He didn’t have a cellphone, either. When he travelled to Ecuador — supposedly to work in construction — there was no way for his family to contact him. He called his mother and sister a week before he committed the crime to tell them that he was fine, not to worry. “After that, we didn’t hear from him. Until, on the news, we started seeing that, apparently, he had killed someone and then, [he had been killed]. It was horrible,” says his sister, Michelle Castillo, in the family kitchen. The balloons and red ribbons that decorated his coffin during the wake are still stored in what was once his room.

Michelle has tan skin, curly hair tied up in a bun and tattoos on her legs and arm. The name of her brother — the most infamous hitmen of recent times — is among them. Ito’s first job — when he was 15-years-old — was as a tailor in a workshop, where he made pants and T-shirts. Afterwards, he was employed on a building site full-time: in the morning, he worked as a laborer and, at night, he acted as a watchman, so that no one stole the brick and plaster. He soon had his first encounter with the law. During a fight, he seriously injured another boy. He was imprisoned for two years in a juvenile prison, between the ages of 16 and 17.

Over the last few months of his life, Ito was unemployed, idle. His sister says that he used to be a joker and very talkative, but that, lately, he had become quiet, taciturn and elusive. He got angry at anything.

Ito had become a father very early, at the age of 15. Even though he didn’t live with the mother and his baby, he wanted to be a present father, unlike his own, who abandoned the household when he was four-years-old. “His father was an irresponsible man. And his mother — my daughter — works like a mule in another house. She spends the day there,” explains Nancy López, Ito’s grandmother.

At the time of the murder, the authorities and the press were writing the killer’s name as “Hito.” His sister clarifies that this was a mistake. She called him that because — when they were little — he moved in bed like a little worm: a gusanito. She settled on the shortened version of this diminutive term, Ito. According to her, he was affectionate. Every day, he opened the door to her room and told her: “Sister, I love you.” His grandmother thought that he was a young man who followed the path of the Lord — every time he passed her, he would praise God.

In the media, however, he is known as a hitman who committed an assassination. The Ecuadorian authorities assume that he had killed before: they don’t believe that whoever organized the murder — likely a drug cartel enraged by Villavicencio’s tough-on-crime rhetoric — sent a novice to carry out the deed.

Ito grew up in a poor neighborhood, with limited economic opportunities. The boys spend the day on the street, with nothing to do. They drink rum from tiny glasses and fantasize about having enough money to buy a motorcycle. Nobody gives them anything: they don’t enjoy any kind of privilege, they don’t have important friends. Oftentimes, they don’t even have an identity card. They don’t exist. When they go looking for a job and say where they come from, they’re immediately rejected. Some of the most prolific gunmen in the history of Colombia grew up in this part of Cali. One boy murdered a total of 32 people. As a child, says a community leader, he had been abused by his neighborhood friends. When he grew up, he wanted to see the world burn. The neighbors closed their doors and hid in their houses when they heard his footsteps from afar. One day — to the relief of many — someone shot him. These guys kill and get killed.

In Ito’s world, it was much easier to keep a gun tucked into your pants and acquire the status of a gangster than it was to find a good-paying, normal job. The criminal networks that hire young men like him give kill orders: for someone unknown — an easy target — they can pay a couple of hundred bucks. If the target has a big name, the price on their head can be $1,000 or $2,000.

Junior Cáceres — tall, thin and thoughtful — smooths his hair while remembering Ito, his brother-in-law. “It’s difficult when you’re young and you have to choose between the bus ticket and breakfast. Or between breakfast or lunch. It’s really difficult. You end up doing bad things. I sometimes warned him about the people he hung out with, but…”

According to authorities, Ito was the one who recruited the rest of the hitmen who traveled to Ecuador. Several of those boys were from Potrero Grande — a nearby neighborhood — which was recently-planned and built by the state, between 2005 and 2008. It was — and is — made up of an extremely vulnerable population. Small, two-storey houses were built, each measuring about 430 square feet. About 39,000 people live in the district, which is divided into rival sectors: young, reckless boys gun each other down. However, in recent years, this violence has decreased greatly, in part due to the work of community leaders and social workers such as Luis (not his real name).

Luis works in the Abriendo Camino (“opening the path”) program, which is dedicated to preventing children from ending up in the world of crime. Many pay attention to him because, when he was young, he himself picked up a gun and killed someone. He spent almost a decade behind bars. Today, he advises the area’s boys that it’s not worth killing someone to buy sneakers and a tracksuit.

Just behind the Somos Pacífico Cultural Technocenter — where Luis spoke with EL PAÍS — a boy was killed just a few months ago. The victim had murdered someone else three years earlier. After getting out of jail, he rebuilt his life, picked up soccer and stayed out of trouble. But the past caught up with him.

Luis wears a Nike cap, a flashy watch and rings. His arms are covered in tattoos. “The boys live with death. I don’t justify what they do, but how do you live if you’re hungry? And if there’s no other option, we always prefer the lesser evil: rob someone, okay, but don’t kill them.”

This commandment came late to 24-year-old Diego Fernando Vargas. He began committing crimes at the age of 12 and committed his first murder at the age of 15. He has only served time for one homicide, but he claims to have committed others. He was in jail from ages 16 to 22. “I liked killing more than stealing. It was easy for me. But not anymore,” he says, while sitting on his motorcycle, with his helmet on. He always wears it in case someone appears around the corner with the intention of taking revenge for what he did in the past. He also keeps a gun in his house. He doesn’t want to get into trouble now, he swears. He has three children: one of them is just a baby. On weekends, he sells salchipapas (pan-fried beef sausages and French fries) from a street stand.

“We try to look for people with leadership. We try to convince the kids [to dream], we say that we’ll help them,” says Juan Camilo Cock. He directs the Alvaralice Foundation, which specializes in delivering social programs. At one point, he notes, Potrero Grande was the neighborhood with the most homicides in all of Cali. The levels of violence have decreased, but schoolkids still meet in the parks to fight. Children grow up in a violent environment. And, as they grow older, they attack each other first with stones, then with knives and, eventually, with guns. While walking through the neighborhood, EL PAÍS comes across some 10-year-old children who are pretending to stab themselves, by using small, sharp sticks.

It’s not easy for some parents to change their opinion about their children. Nelson López thought that his son was “a good boy” who didn’t get into trouble. One night, he came home and he was gone — he had vanished. His son had gone to Ecuador, because life in Colombia was unbearable. He made a living washing cars or laying bricks. He was looking for something better, something that would take him out of mediocrity. During the time he was in Ecuador, he never communicated with his parents. He didn’t call them, not even once. This was odd, as José Neyder López Hitas was a very family-oriented kid.

The next time they saw his face, he was in a police photo, along with five other Colombians, who were suspected of having participated in the murder of the Ecuadorian politician. The photographs reaffirmed Colombia’s reputation as a country that exports hitmen. Seventeen former soldiers — all of Colombian origin — are currently imprisoned for having murdered Haitian president Jovenel Möise, back in 2021. And, on the beaches of Cartagena, along the Colombian Caribbean, Paraguayan anti-mafia prosecutor — Marcelo Pecci — was recently shot to death.

In Nelson López’s small room — hidden behind a curtain — a Christian radio station plays: “Abraham knew that God was powerful enough to give him everything he had asked for.” The man touches his head and stares into space, as if trying to escape from his nightmare for a few moments. He took José Neyder to the evangelical church when he was a child, but as soon as his son grew up, he refused to go. He hoped that, despite this, something divine had nestled in his heart. But suddenly, he woke up and realized that his son had become a murderer. “He was a sensitive boy. I don’t know why he decided to make this decision. Maybe he was influenced by other people.”

“I pray for him every day,” the father sighs.

A couple of streets away, the fish in the tank and the cockatoos and parrots locked in cages have been left without an owner. Like everyone who appears in this story, one day, Andrés Manuel Mosquera left home and didn’t return. He is 30-years-old. Dressed in a tracksuit with a white T-shirt, he is the shortest of those in the police photographs that have been released. He has a criminal record for manufacturing weapons, which — according to his mother — closed the doors to many legitimate jobs. He served the sentence for this crime under house arrest.

“I never felt that something was wrong,” says Diana Patricia Mosquera, his mother. The day her son left the house, he had a soda, a piece of bread and a glass of juice. He said he was going to work in Ecuador, so that he could provide for his two daughters. It was the first time he ever left Colombia.

Diana types “Fernando Villavicencio” into the Twitter search engine every day, in case any news about her son appears. The Ecuadorian Attorney General’s Office has charged him with the crimes of murder and drug-trafficking. The consulate has sent the mother the requirements to be able to visit her son in the Guayaquil prison where he is being held, but she doesn’t have the money to make the trip.

Andrés Manuel enjoyed boxing and dancing. In his room — which doesn’t have a door — he left behind a fan, a speaker, some baseball caps and two pairs of sneakers. Everything is scattered — as if he planned to return the next day. His sister, Tania, believes that he’s innocent. Her theory is that the police arrived at the tenement where his brother lived, in Quito, and took away all the Colombians who were present.

The police, however, place them all at the crime scene — a crime that someone else planned. They were the ones executing it. The authorities have identified them all as having been present within the eight minutes that passed between the politician leaving his rally, until the moment that Ito was shot down. Two other people involved were arrested, while two more escaped on a motorcycle, shooting as they fled.

For all of this to have taken place, three boys had to leave their neighborhoods in Cali to embark on a suicide mission. The role played by José Neyder and Andrés Manuel is still unknown, but what’s certain is that Ito stood in front of the SUV and started shooting. He killed his target, but within minutes, death would also claim him.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.