Salvador Allende, according to biographer Mario Amorós: ‘An elegant freemason, far from the typical image of a socialist revolutionary’

An updated biography describes with new documentation the life and political trajectory of the former Chilean president, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of his death

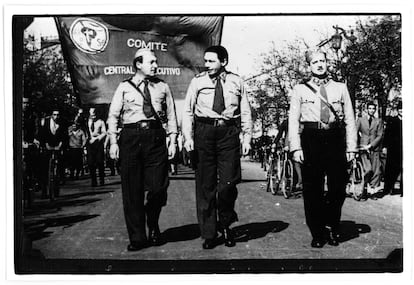

Salvador Allende (1908-1973) was born into a wealthy middle-class family. As a teenager, he met anarchist Juan Demarchi in Valparaíso (Chile), who taught him how to play chess and talked to him about social injustice and working class struggles. Demarchi, a carpenter of Italian origin, greatly influenced young Allende who, as a medical student, decided to become a socialist and enter politics to combat inequality in his country. “He was one of four doctors among the 500 activists who founded the Socialist Party of Chile,” said Mario Amorós, who wrote an updated biography of the former Chilean president (1970-1973) a legendary leftist who died in the military coup d’état led by Augusto Pinochet.

“Allende was an elegant freemason, far from the typical image of a socialist revolutionary,” said Amorós. “He enjoyed good food, liked women, dressed elegantly, exercised regularly and ate a balanced diet. Socialists criticized him for all that and other things. He owned a small boat and people said it was a big boat. Allende is revered by many as a left-wing icon who aimed to peacefully establish a socialist society, without violent class confrontations. His vision transcends social democracy because he strove to unite the socialist and communist parties, and advocated for democracy, human rights and a revolutionary form of socialism.”

The 50th anniversary of Allende’s death on September 11 has inspired public events, meetings, articles, and publications about the president who stayed and ultimately died in Moneda Palace while it was being bombed during the coup. Mario Amorós is a historian and journalist whose update of his 2013 biography includes new documentation discovered in various archives. He explores Allende’s relationship with the Christian Democratic Party in Chile and delves into his efforts to bring about change by addressing hunger and poverty, and later safeguarding democracy to prevent a coup. Although Allende and his Popular Unity (UP) party won a majority of the vote in the 1970 general elections, this sparked debate among Christian Democrats about whether to honor the tradition of declaring him the winner.

“Ultimately, the Christian Democrats lent their support, yet in June 1971, a significant divide emerged, skillfully exploited by the most ardently anti-communist factions of the conservative movement. Their claim was that the Allende government was paving the way for a Stalinist-style dictatorship, a charge that Allende consistently refuted. Numerous ideological biases permeated the landscape, casting shadows on the political climate,” said Amorós, who has authored biographies of Víctor Jara, Dolores Ibarruri, Pablo Neruda and Augusto Pinochet.

In 1973, following the coup in Chile, Enrico Berlinguer, the general secretary of the Communist Party of Italy (PCI), proposed a historic compromise to form an alliance with the Christian Democracy. Despite the support of Christian Democrat Aldo Moro, the proposal was rejected by both the United States (which had backed the Chilean coup) and the USSR. Chile’s socialist era was a significant event in its time, marked by a tragic end. In his famous farewell speech to Chileans on live radio (Radio Magallanes) before his suicide, Allende said, “Surely this will be the last opportunity for me to address you. The Air Force has bombed the antennas of Radio Magallanes... I am certain that my sacrifice will not be in vain, I am certain that, at the very least, it will be a moral lesson that will punish felony, cowardice, and treason.”

Amorós does not hide his leftist leanings. “I have deep affection and admiration for Allende. However, that doesn’t mean I avoid critical reflection or overlook the mistakes made by Allende and the left. One such mistake was Allende’s failure to understand the Chilean military’s reliance on the United States during the Cold War. For instance, Allende believed that Pinochet, whom he appointed as head of the army, would support democracy. Despite these shortcomings, I want to highlight the achievements of Allende’s government and policies. These include addressing landownership through agrarian reform, copper mining reforms, and social programs like providing daily milk to children. I also delved into Allende’s cultural and health care policies, and his overlooked but influential role in international relations as a leader of the Third World and non-aligned countries. I have documentation on all these topics.”

In his book, Amorós presents a comprehensive account of Allende’s political career, not just his presidential years, which have been thoroughly studied by scholars. He analyzes significant events like Allende’s compelling speech at the United Nations in 1972, his meeting with Ho Chi Minh (Vietnam), relationship with Fidel Castro, remarks about Stalin’s death in 1953 in which he acknowledged the crimes of Stalinism, and his opposition to the Soviet invasions of Hungary and Czechoslovakia. The biography also touches upon Allende’s personal life without delving into the more private aspects that Eduardo Labarca explored in his 2005 biography of Allende.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.