The prisoner who impersonated a Chilean minister and put President Boric against the ropes

The man behind the theft of 23 computers from the department headed by Giorgio Jackson is a 24-year-old criminal who made a video call from jail

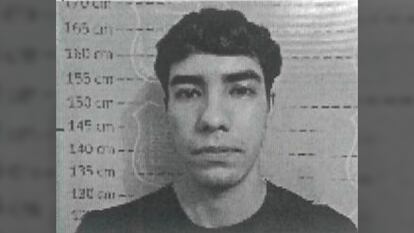

Last Wednesday night, a 24-year-old criminal named Miguel Angel Apablaza—nicknamed Negro chico—carried out an unusual robbery against Chile’s Ministry of Social Development. He did so from inside the Puente Alto penitentiary, in the south of Santiago, the capital of Chile. Using just two cellphones (commonly used in Chilean prisons), he pretended to be Giorgio Jackson, the Minister of Social Development and President Gabriel Boric’s main political ally. Apablaza called the building’s two security guards at night and managed to steal 23 laptops, a safe deposit box and other items from Jackson’s own office inside the ministry building. The robbery has shaken Chilean politics and Boric’s leftist government.

In an operation that lasted three hours, between 8:30 p.m. and 11.30 p.m., three of Apablaza’s criminal accomplices moved freely through the ministry building, demonstrating the ease with which the security of some of Chile’s public offices can be breached.

The details of the robbery were made public on Friday afternoon during the initial hearings of the two participants who have been identified so far: Apablaza himself—who is currently serving a prison sentence from 2018 to January 2027 for robbery—and his 60-year-old grandmother, Elena Rojas, who received the computers; she was placed under house arrest, at the request of prosecutor María José Grez, of the North Central Prosecutor’s Office.

According to the prosecutor’s version of events, on Wednesday night there were two security guards working at the reception desk inside the ministry building on Catedral Street. A 61-year-old employee named Lasso, from the private security company HM, answered the call on the ministry’s landline at about 8:30 p.m. “Hello, I am Giorgio Jackson, and I’ve had an accident,” said a man on the other end of the line. Apablaza then proceeded to explain having had an accident in the southern area of Santiago, Chile, in the municipality of San Bernardo, and said that he needed a tow truck to pick up his car.

The alleged minister explained that he did not want his wife to find out what had happened, and that he preferred to communicate via cell phone and WhatsApp (the real Jackson is unmarried and does not have children). Lasso and his colleague, whose last name is Guzmán, were convinced that they were talking to the minister, but they did not have the Whatsapp application on their own phones, so they looked for the ministry’s security company’s cellphone and gave him the number.

On a video call—which only displayed a man’s photograph (“you could only see the picture of a person wearing a cap, with a white complexion and eyeglasses, who actually looked just like Minister Giorgio Jackson”)—the impostor began to give orders to the two night workers. First, he instructed the security guards to remove 50 laptops from different floors of the ministry; he claimed that the machines had to be updated. Guzmán went up to the offices and, obeying instructions, removed the laptops; because they were tied down with chains, he had to use a chain cutter, which he got in the same building. He managed to take 23 computers and put them in two black plastic garbage bags that he requested from a member of the cleaning crew. One of the computers belonged to Jackson himself. According to the prosecutor, nine people, including the two guards and a cleaning lady, were working inside the building at the time.

The guard also put a medal and three pins from the minister’s office in the bags. According to the instructions he had received, he was supposed to take 15 medals from the office.

The security workers were also instructed to give the bags to a driver who would arrive to pick them up. Shortly before, an Uber driver had received a text message that said: “Hello, good evening, I am Giorgio Jackson, Minister of Social Development and I am waiting for you at the ministry. Please wait there; the whole trip is going to be paid for.” (On Friday, the prosecutor explained that the driver was not connected to the crime.) The Uber driver then transported the computers to a street in the municipality of Renca, in the northern part of Santiago, where Apablaza’s grandmother collected them. Three other people—two men and one woman—joined Rojas, and she paid for the Uber through a bank transfer from her personal account.

Still pretending to be Minister Jackson, the perpetrator informed the guards through the WhatsApp video call that he would send his nephews to the ministry’s premises to fumigate the building. He made it clear to the guards that they were “trustworthy.” Then, three men wearing white overalls and light blue surgical masks covering their faces arrived at the building on Catedral Street with a loading cart.

According to the instructions, prior to the fumigation, the guards were to remove the safety deposit box located on the Ministry’s fifth floor. They did just that. According to information from the Ministry, the safe contained financial guarantee documents, checks and corporate bank cards, all of which have since been blocked.

The three criminals—whose faces were barely visible, according to the prosecutor’s account—covered the box with a garbage bag and put it on the loading cart; then they left in another car. There has been no trace of them or the safe deposit box.

A cleaning worker named América became suspicious of the unusual movements in the building at night, and of a minister talking with a security guard for so long. She contacted her bosses at the cleaning company by telephone, who instructed her to call the Carabineros [police]. América then alerted the rest of the people in the building, including the security guards, that they were being scammed. When security guard Guzmán received the alert, he was still on the video call with the supposed minister Jackson and confronted him about it. The thief answered: “Look, motherfucker, I just screwed you over” and hung up. It was around 11:30 p.m. Shortly thereafter, the police arrived from a nearby police station.

That same night, Apablaza called his grandmother and asked her for photographs of the bags with the computers. Then he ordered her to go to the same corner as the previous night again and deliver the merchandise to another Uber car that would arrive to pick it up on Thursday at 2 p.m. But two police officers showed up at her house and recovered the 23 computers. Rojas, who has a criminal record for drug trafficking, told the prosecutor that her grandson must have received orders from someone. Through her, prosecutors confirmed that the two numbers used in the robbery belonged to her imprisoned grandson.

On Friday, Apablaza was transferred to a high security prison.

A minister in the spotlight

The crime has put Boric’s government against the ropes and had important political consequences. Jackson is one of the leaders and founders of the Democratic Revolution party, a political force in Boric’s Broad Front that has been at the epicenter of the so-called “Convenios [Agreements]” Case.

The “Convenios” plot emerged last June and involves investigations by the Prosecutor’s Office into the transfer of millions of State funds to non-profit foundations, primarily linked to the Democratic Revolution party. This Friday, the Independent Democratic Union—a traditional right-wing party and one of the most important members of the opposition—froze its talks with the government and will not resume them unless President Boric removes Jackson from his Cabinet. This move comes amid political negotiations over tax and pension reforms, in which the opposition’s votes are crucial because the executive does not have majorities in Congress.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.