A spy balloon, a letter to Biden and the specter of interventionism: López Obrador briefing brims with complaints against US

A day after hosting Joe Biden’s homeland security advisor, the Mexican president again ratcheted up tensions by accusing Washington of meddling in his country’s affairs

In his morning press briefing Wednesday, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador again decried U.S. interference in its neighbor’s affairs. López Obrador denounced an orchestrated “campaign” of espionage against Mexico’s Secretariat of National Defense, unveiled a letter complaining about the U.S. State Department’s funding of domestic “opponents” and revealed that he had denied America’s armed forces permission to shoot down a “spy balloon” over Mexican airspace. At the same time, he praised U.S. President Joe Biden and insisted that relations between the two countries are in positive health. This all came a day after López Obrador hosted U.S. Homeland Security Advisor Elizabeth Sherwood-Randall to discuss fentanyl and migration. “I hope they revise this policy of meddling, because it is offensive and it is arrogant,” he said. “They act as if the whole of the Americas belonged to them.”

López Obrador began the Q&A section of his press briefing by saying that his relationship with President Biden “is very good”, referring to his U.S. counterpart as “a person who respects our sovereignty” and “a friend of Mexico”. He then launched into a long historical explanation that argued that the Monroe Doctrine — “America for the Americans” — remains the guiding beacon of U.S. foreign policy and the origin of its frictions with the Mexican government. “The U.S. navy invaded countries [and] created countries, associated states and enclaves; it installed and removed presidents. That time-old policy has, unfortunately, survived to this day — remnants of it remain,” López Obrador declared, before heaping praise on Cuba, which he said has endured “an inhumane, unspeakable embargo that violates international law”.

“Whichever party is in government [in the U.S.], there are certain long-standing policies that are highly interventionist — that’s nothing new,” he added. López Obrador then talked of former U.S. President Donald Trump’s “anti-Mexican and anti-immigrant discourse”, but acknowledged that this “changed” during Trump’s time in the White House. The two countries were able to strike deals, he noted, even reversing a plan to designate Mexican drug cartels as terrorist organizations — a proposal that has resurfaced among the most recalcitrant conservative circles ahead of the presidential elections in both countries next year. López Obrador also thanked Trump for ceasing his talk of building a wall on the U.S.’s southern border; for recognizing the contribution Mexicans make to America’s economy; and for reducing U.S. intervention in Mexico, despite incidents such as the failed capture of the drug lord Ovidio Guzmán in 2019, and the LeBarón family massacre the following month. “We have to protect our sovereignty; we can’t let anyone in,” López Obrador said.

Returning to the present, the Mexican president again praised Biden, and said with surprise: “Now it turns out that this is when we’re noticing the most interference — [but] not by the president. The United States government has many agencies, and many of these agencies — I say so respectfully — are acting improperly, without respect; they’re acting very arrogantly.” This is the basis on which López Obrador has become embroiled in disputes with the Pentagon, hinting that it is behind the largest cyber-attack ever suffered by Mexico’s armed forces; with the State Department, which has criticized his relationship with civil-society groups and the media; and over the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s (DEA) intelligence work against Mexican cartels. “It has nothing to do with President Biden’s attitude,” he said.

“The Secretariat of Defense was hacked, and that is not done here,” López Obrador said. “These hacks have also been carried out in other Latin American countries. I say this with a lot of respect, because they are independent, but as a recommendation, the United States Congress ought to open an investigation into this, because espionage doesn’t help relations.” The president also spoke of an “excessive campaign” against Mexico over its refusal to allow U.S. armed forces to shoot down a spy balloon this week. “They wanted to fly over our airspace with planes and drones of a high military and technological level, because they had detected a balloon that was coming from Hawaii and was going to pass over Mexico, and they insisted that it was a balloon from Asia,” López Obrador said, without specifying which Asian country (“I don’t want to get involved in these matters”). “The answer was ‘no’,” he said.

López Obrador went on to explain that he asked U.S. authorities to send information on the object so that Mexico could take action. “We carried out an operation with planes and drones, we were told that it was a balloon flying at an altitude of 35,000 feet,” he said. “It was going to enter [Mexico] the day before yesterday at 3 a.m. [local time] over Manzanillo [on Mexico’s west coast] and leave over Tamaulipas [on the east coast]. But we didn’t detect anything, nor did they tell us that they had seen it.”

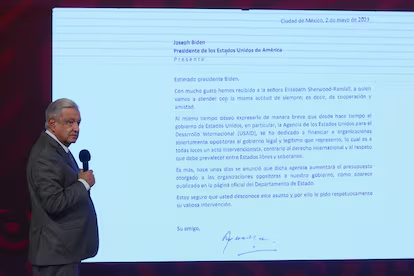

After the Pentagon, it was the turn of the State Department. López Obrador unveiled a letter that he is to send to Biden amid reports that the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is to increase its funding of civil-society groups in Mexico. In the communication, the Mexican president wrote that USAID “has set about financing organizations that are openly opposed to the legal and legitimate government that I represent.” continuing: “It is plainly an interventionist act that is against international law and the respect that should prevail between free and sovereign states.”

It is a letter that speaks volumes for the countries’ mixed bilateral relations. “We were delighted to host Ms. Elizabeth Sherwood-Randall, whom we are going to treat with the same attitude as always: one of cooperation and friendship,” the letter, dated Tuesday, begins. Just a matter of hours earlier, both governments had issued a joint statement detailing newly-agreed migration measures. The U.S. has committed to giving humanitarian visas to 300,000 citizens of Haiti, Venezuela and Nicaragua, as well as 100,000 similar permits to people from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. In exchange, Mexico has agreed to continue to accept non-Mexican migrants deported over the southern border, where the end of exceptional measures brought in amid the pandemic has revived fears of a huge bottle neck. This week, Mexican authorities revealed that more than 70,000 migrants were detained between January and February, almost 50% more than in the same period in 2022. López Obrador didn’t go into detail on the key issues of his meeting with Sherwood-Randall. He also didn’t talk about Biden’s decision to send military troops to protect the border.

“I told her in private, briefly, that to avoid upsetting President Biden, I wasn’t going to send a letter that I had already written,” López Obrador said of his conversation with Sherwood-Randall, who he described as “very friendly” and “an extraordinary diplomat.” “I told her that [USAID’s increased funding of civil-society groups] saddened me, because [Biden] has treated us very well,” he added. In the end, he revealed, he reconsidered and opted to send the letter, which was projected onto a big screen during Wednesday’s press briefing. “I can’t stay silent,” he explained.

At the end of his four-paragraph letter, López Obrador adopts a more conciliatory tone with Biden. “I am sure that you are unaware of this matter, and that is why I respectfully request your valuable intervention,” he wrote. Under the Mexican president’s logic, the State Department, the Pentagon and the DEA have so much power and room for maneuver that they don’t have to consult his U.S. counterpart on delicate matters relating to Mexico. And that, he insists, allows him to treat his relationship with Biden and U.S. governmental agencies separately.

It seems highly unlikely, however, that all these agencies and institutions, which are subordinate to Biden’s executive, can act behind the president’s back. According to López Obrador, it is worthwhile taking Washington to task over its perceived interference because, in the leftist president’s view, “[Mexico’s] conservatives are traitors to their country who don’t mind a foreign government making decisions that should exclusively be made by the Mexicans”. Biden, for his part, has shown no interest in responding publicly. Last week, he announced his candidacy for reelection as U.S. president, with a second ballot-box battle against Trump seemingly in the offing.

Amid philias and phobias, the Mexican president spent more than 45 minutes setting out his view on his frictions with the U.S., his historical and geopolitical interpretation, the mistrust that prevails in key areas of the bilateral relationship, the nations’ disagreements when it comes to exchanging intelligence, the decision to make his letter to Biden public, and López Obrador’s belief that he is strengthening Mexico’s position. “This won’t harm us — it will help us politically,” he declared. “That’s all there is to it.” A spy balloon, a letter of complaint and the age-old specter of interventionism are the latest points of discord between the Mexican and American governments.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.