The underground bankers of the people smuggling business

The traditional ‘hawala’ money transfer system provides financial services to human traffickers and migrants on dangerous journeys to the EU and the UK

Zanyar felt that there was no future for him in his homeland. So he left, like many other young people from autonomous Iraqi Kurdistan. Mustafa understood his son’s decision. “Everything has gotten worse since the Daesh [the Islamic State terrorist organization] came.” Mustafa is a Peshmerga (Kurdish military forces) soldier who fought bravely with Western coalition forces against the jihadis in 2015 and 2016, but only gets paid every two or three months because of the country’s political paralysis and distressed economy. “Zanyar dropped out of school because other people who graduated couldn’t find work. How was he going to get married and start a family with no job? He wanted to go to the UK and become a barber,” said Mustafa.

But Zanyar’s dreams were shipwrecked in the English Channel in the early morning of November 24, 2021. His boat sank and most of the 30 people aboard drowned or died of hypothermia. The coast guard didn’t make it in time to rescue them, an incident that is still being investigated in a court case implicating France and the United Kingdom.

Irregular migration to Europe is not only difficult and dangerous, it’s also extremely expensive. Crossing the Aegean Sea from the Turkish coast to the Greek islands in an overcrowded inflatable boat can cost $1,000-$3,000, depending on the season. The legal route on a ferry costs about $20. A plane ticket from Istanbul to Italy is less than $300, but that same trip can cost an irregular migrant over $10,000. Travelers with visas can take a ferry ride across the English Channel for $35. With no visa, a risky trip in a small dinghy costs $3,000.

“We pour our lives into this journey. We take on debt to pay the smugglers and everything else we need for the journey,” said a migrant as he stood on a French beach waiting to cross over to the UK last July. It was the same place where Zanyar boarded the boat and later drowned in the English Channel. The young Kurd’s father had to mortgage some of his land to finance his son’s ill-fated journey.

The almost total lack of legal mechanisms for migrating to the European Union has created business opportunities for criminal networks. Europol and the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) estimate human traffickers earn $350-$750 million a year smuggling migrants to Europe. Whenever that much money is at stake, a financial system is needed to handle it all — a system that looks like a bank.

For the past year, a group of journalists has investigated the route Zanyar used to find out how the money moves though this illegal business. They interviewed dozens of people in Iraq, Turkey, Spain, Italy, France and the UK, including migrants, smugglers, middlemen, sources in the police and justice systems and other experts.

The hawala network

At the Erbil Money Exchange Market (also known as the dollar bazaar) in northern Iraq, moneychangers lug around enormous stacks of banknotes the size of an old television. People shout out their wares — US dollars, Iraqi dinars, Syrian pounds — that they sell to the highest bidder. Money moves constantly from hand to hand on the shabby floor of this foreign exchange market. Dozens of money order agencies dot the streets, back alleys and underground corridors of the dollar bazaar. Some agencies only deal with Iran, while others focus on Germany and France. Still others claim they can send money all over Europe or anywhere in the world. But instead of the normal international banking channels, many use the hawala network.

The hawala network is as old as the ancient Eurasian Silk Road trade route when it was used to facilitate payments between merchants, so they didn’t have to carry large sums of money on long journeys. This is how it works. A customer in Iraq, for example, goes to a money broker — a hawaladar — and gives him money he wants to send to someone in France. The Iraqi hawaladar communicates with a trusted French hawaladar and asks him to disburse the same amount to the recipient, who must identify himself with a token or security code established by the Iraqi hawaladar. The Iraqi hawaladar now owes the French hawaladar, who will be repaid by similar transfers in the opposite direction.

A hawaladar’s office can be nothing more than a table and chair, a mobile phone and a cabinet or safe to store money. Some have notebooks to document the transactions, although people now use their mobile phones and delete the message as soon as the debt is settled. There is no SWIFT or blockchain system to record transactions, nor do the hawaladars exchange promissory notes or other legal documents to secure the debt. In the vast hawaladar network, what matters is performance, trust and honor. Georgetown University sociologist Gözde Güran has researched the hawala network extensively and says these bonds of “interpersonal trust” are very strong, because any betrayal would irreparably destroy a reputation. Which is why these informal long-distance business relationships thrive and endure.

Many migrant communities use the hawala network to send money home, especially when home is in a remote town in Iran or Afghanistan, countries with weak banking infrastructures marginalized from the global financial system. It’s an attractive system because the cost of the service is usually much lower than international money transfer systems like Western Union or MoneyGram, who charge up to 15% for the service. Those systems also require official documents from the sender that irregular migrants do not have. The hawaladars usually charge about 5% and often less. An Erbil hawaladar said, “sometimes they don’t charge anything” if the transfer settles a debt in some out-of-the-way place where few remittances are sent.

Even Western non-governmental organizations use the hawala network to send money to war-torn countries like Syria, says Güran. Since no money is physically moved and there is no paper trail except maybe a few lines in a tattered notebook, experts say the hawala network has become the preferred money transfer mechanism for criminal groups and terrorist organizations. Many countries have outlawed the hawala network for this very reason.

Migrant insurance policies

At the peak of the 2015 European refugee crisis, the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol) estimated that half of the migrants paid for their journey in cash and the rest by various methods, including via hawaladars. But various sources say direct cash payments to smugglers are declining, and intermediaries are now used, many of whom operate through the hawala network.

“No one carries that much money on them. Foreigners in a strange land are afraid that they’ll be robbed, so payment is made through intermediaries,” said Sherko (a pseudonym), who runs a travel agency in downtown Ranya (Iraqi Kurdistan), a frequent departure point for many migrants. In the 2000s, Sherko migrated back and forth to Europe several times, but decided a few years ago to stay home and start his business. Besides booking tickets and providing visa information, he serves as an intermediary between migrants and smugglers for a commission. “People want to leave, no matter what,” said Sherko, justifying this service that many other local businesses also provide. “We find them the best smuggler, so they don’t get ripped off or robbed. Sometimes these smugglers don’t keep their promises — after all, it’s not like buying a plane ticket with a set departure date and time.”

When Zanyar left home, his father told him, “Find a good smuggler in Turkey, one who will give you guarantees, and I’ll help you out.” Zanyar’s first attempt at getting to Europe three years earlier ended with him getting beaten up by the Bulgarian police. All his belongings were stolen, and he was forced to return home. In 2021, he decided to travel by sea. His father deposited $12,000 with a hawaladar in Ranya, who put a hold on payment until Zanyar safely reached Crotone on the Italian coast, when it was released to the smugglers in Istanbul.

“We make sure the smugglers don’t cheat people, so we don’t pay until they reach their destination,” said a hawaladar in the UK. “I help 20 or 30 people come here every year and we’ve had no deaths or injuries so far. If a customer backs out, the smuggler only gets half the payment.”

This practice is a migrant insurance policy, especially when illegal deportations have become so commonplace at the EU’s border points. With a third party holding the money, a smuggler has to keep taking migrants back until they successfully make it to their destinations.

“We never returned money, but if there was a problem, we offered a new attempt,” said Samir (a pseudonym), a Syrian who helped smuggle 300 people from Turkey to Greece between 2015 and 2018. His job was to go with the migrants to a “deposit office” (a tamin, in Arabic), which was usually disguised as a foreign exchange or international money transfer agency. “Everybody knows about these places, including the government. Nobody messes with them because everyone trusts and uses them.”

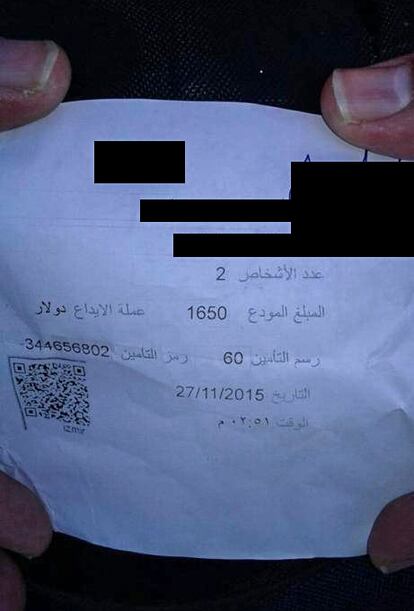

At the tamin, the migrant deposits the agreed amount and receives a signed and stamped receipt with all the pertinent information: payer and recipient names, amount and currency, commission (3.5%-4.5%), date and security code. Once migrants reach their destinations, they send a message via WhatsApp or another app with a photo of the receipt or the security code. Only then can the recipient withdraw the money. “There’s also an agreed time period — usually one month — after which the smuggler can get paid if the migrant hasn’t sent the code.” said Samir.

Samir admits a migrant could get cheated if the intermediary colludes with the smuggler, but this rarely happens. People usually turn to intermediaries in their home countries or in Istanbul (a major hub on migration routes to the EU) of the same nationality or ethnic origins. A hawaladar “wouldn’t ruin his reputation” by scamming people, says Mustafa. “We are old school here. If he did something like that, no one would ever do business with him again.” If confidence collapses, so does the financial system, just like a regular bank.

On the coast of Dunkirk

It’s a cold, wet January morning in Grande-Synthe (France), a Dunkirk suburb on the English Channel. Kurdish-Iraqi journalist Aisha (a pseudonym) and her two daughters huddle around a campfire next to plastic makeshift tents along the railroad tracks. “I was in Dunkirk for a month with an NGO that helps women and children,” said Aisha. “But we’ve been here for the last three nights because we want to cross the Channel. I fled my home because I was being persecuted for my work. I first flew from Iraq to Istanbul, and from there we traveled to Croatia by land using a smuggler. In Croatia, I was beaten by the police. Then I got to France with the help of another smuggler. Every time I cross a border, I send a WhatsApp message to give my father our location. Then he tells the nosinga [a hawaladar in Kurdish] to pay the smugglers.”

This is how Zanyar spent his last days a little over a year earlier — waiting in Dunkirk for a month. The weather was bad and the boats worse, so he couldn’t cross the Channel to England. “He was very unlucky,” said his father, who had deposited $3,100 with a local hawaladar to pay for the last leg of his son’s journey. Eventually, Zanyar and a friend found a Kurdish-Iraqi smuggler named Bajdar to take them across. The weather was still terrible, but they went anyway.

“The boat could safely hold 20 people, but they set out with more. They called the smuggler and said they were turning around because the boat was taking on water. But the smuggler threatened to kill them if they returned,” said Ismail Hamad, the father of another victim, at his home in Soran (Iraqi Kurdistan).

While the hawala system provides insurance for migrants, it also pressures smugglers to deliver, so many will press on just to get paid. Many intermediaries refuse to pay a smuggler if the migrant dies and will return the money to the family. “There are a few good smugglers who won’t pressure a migrant who wants to back out,” said a migrant in Calais (France). “But 90% of them aren’t like that. They’ll even force you to board the boat.”

Swamped by the enormous influx of irregular migrants across the English Channel (almost 46,000 last year, 60% more than in 2021), the Conservative UK government has proposed a law imposing a lifetime ban on asylum-seekers arriving by boat. Last year, it struck an agreement with Rwanda to hold deported migrants in camps while they apply for asylum.

But curbing irregular migration is like trying to fetch water with a sieve. “Since we have no way to immigrate safely and legally, we have to go to a hawaladar,” says Goran, a 19-year-old Kurdish-Iraqi who is waiting in Dunkirk. Another young Kurdish man from Iran joins the conversation. “Even if they [authorities] try to go after the hawala network, people will find another way, like using a nosinga who’s not on anyone’s radar.” For the foreseeable future, smugglers and hawaladars are sure to thrive as they serve the millions of people whose only option is to make dangerous journeys seeking better lives.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.