Humberto Ortega and the political chess match in Nicaragua

The millionaire businessman and former army chief has presented himself as a strategist and conciliatory figure within the Sandinista regime, despite disagreements with his brother, President Daniel Ortega

Recently, a stir was caused in the Nicaraguan capital of Managua when President Daniel Ortega paid a visit to his brother, Humberto, the former head of the country’s Armed Forces. The rift between the two brothers is widely known: Humberto Ortega – in addition to having political differences with the president – has criticized his brother’s shift towards authoritarianism.

Government spokespeople said that the visit was made due to Humberto’s delicate state of health, although his family has stated that he is in good shape. What was discussed behind closed doors inside the over-the-top Managua mansion has not come to light. Yet this hasn’t stopped speculation from running wild, given that Humberto is strongly linked to his country’s recent history, with many blaming him for atrocities committed during his command over the army in the 1980s.

During the Nicaraguan Civil War, it was alleged that Humberto took advantage of his political and military power for personal enrichment. However, he sees himself as an enlightened historian and strategist – someone who can play the role of a mediator in Nicaragua’s ongoing political crisis, which began in 2018.

Humberto Ortega was born to a working-class family in Managua in 1947. His parents – Daniel Ortega and Lidia Saavedra – had moved from the countryside and settled in a poor neighborhood in the capital, to raise their four children in a country that was being looted by the ruling Somoza family. The Somozas ruled Nicaragua as a corrupt dictatorship from 1936 until 1979.

From a very young age, Humberto became involved in the guerrilla struggle. But when he was barely 22, in 1969, he participated in a failed attack on a prison in neighboring Costa Rica, where Carlos Fonseca Amador – the founder of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) – was being held. Humberto, who along with his fellow guerillas wanted to free the movement’s leader, was wounded in the prison break, which impeded his ability to participate actively in the armed uprising against the dictatorship.

“Everything went wrong. Carlos Fonseca was recaptured less than three hours after the rescue operation. Humberto Ortega was about to bleed to death… he lost movement in one of his hands and was [no longer] fit for war. The Costa Rican policemen captured part of the rescue group,” wrote journalist Eduardo Cruz, in a profile of Ortega for Magazine, a supplement published by La Prensa, one of Nicargua’s leading newspapers.

His older brother, Daniel, also became involved in the Sandinista struggle, although his initial involvement was not very fruitful either. Daniel joined the FSLN in 1963, after hearing about the movement in the corridors of the Jesuit-run Central American University (UCA) – a powder keg for young insurgents – where he was studying. He moved from political activism to action. In 1967, he participated in a bank robbery to finance the clandestine struggle: he ended up being arrested and sentenced to seven years in prison.

These setbacks temporarily demoralized the brothers, but ultimately did not undermine their desire to take down Somoza. The Ortegas were part of the so-called Tercerista Tendency (the third way) within the Sandinista movement – a more pragmatic group that attempted to extend the guerrilla struggle into the cities and involve the bourgeoisie. This angered many hardened Marxists, who belonged to the Proletarian Tendency and the Maoist bloc of the Nicaraguan Revolution.

Despite their differences, the three factions managed to unite in March of 1979. In San José, Costa Rica, they created a joint national leadership within the FSLN, thereby guaranteeing “the unbreakable unity of the Sandinista Front,” according to a statement released at the time. By the end of the 1970s, Costa Rica had become a place of exile for thousands of Nicaraguans who eventually oversaw the end of the dictatorship.

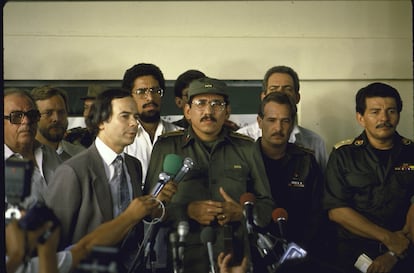

It was from San José that Humberto Ortega – already one of the main leaders of the FSLN – announced that the guerrillas would launch what would be called the “Final Offensive” against the government of General Anastasio Somoza. He asked Nicaraguans to rise up against the regime.

“Ortega also urged the members of the Armed Forces to lay down their arms, so that, in this way, they could save their lives. Ortega said that the guerrillas and the Nicaraguan people were fighting from North to South and from coast to coast throughout Nicaragua,” reported a dispatch from the EFE news agency.

In April of 1979 – in an interview with EL PAÍS – Humberto emphasized that he and the movement’s followers were in a “pre-insurrectionary situation.”

“The total insurrection will come soon. It will be very difficult to stop the people, who are already very radicalized. They will create the final rebellion – we [the FSLN] are only the armed instrument of the masses. That’s why we’re already in this [revolutionary] phase in the cities and we see that, despite the repression [of the Somozas], the people support us.”

The Sandinista Revolution triumphed in July of that year. Daniel and Humberto Ortega reached the pinnacle of power in Nicaragua. At age 32, Humberto was called upon to organize and command the Sandinista Army, which would replace Somoza’s National Guard.

At the time, sources in Managua complained that Humberto Ortega’s capacity as a strategist also generated resentment among others within the Sandinista leadership. They feared that the resulting disputes would break up the FSLN. It was Humberto who found a solution to defuse tensions: he proposed that his apparently harmless brother occupy the highest government position.

In his 1979 interview with EL PAÍS, Humberto clearly stated that Nicargua “would not become another Cuba” or adopt a “radical left-wing extremist system.”

“We’re going to make our own revolution, with the Marxists and the non-Marxists,” he explained.

However, reality proved otherwise. A source consulted in Managua – who prefers to remain anonymous – affirms that one of the first mistakes made by Ortega and the leadership of the Sandinista Front was to reject the military aid offered to them by the administration of US President Jimmy Carter. “That was a very important mistake.”

It is at that moment that the Sandinistas showed they were willing to move closer to Havana and Moscow. According to this source, Ortega’s thinking was that “if they took US weapons and the revolution became radicalized, Washington could cut off supplies. That would be dangerous.”

While the young Sandinista leaders played the international chess game that was the Cold War, popular discontent began to build internally. Nicaraguans frowned upon the aftermath of some of the expropriations that were carried out following the revolutionary triumph.

Many of the properties belonging to the Somozas and the Somoza-aligned oligarchy were initially confiscated in 1979. A large part of them were put at the service of the revolution, with the organization of collective farms and the nationalization of certain industries. However, the Sandinista leaders also began to move into the biggest houses in Managua’s best neighborhoods. In some cases, these revolutionaries were living in lavish mansions with huge pools, embedded like jewels in the middle of tropical gardens. This life of luxury contrasted greatly with the sacrifices being asked of the population.

Humberto Ortega is often accused of being one of the leaders who succumbed to the good life. Sources consulted for this report affirm that his vast net worth has roots in those revolutionary years, having grown substantially when he commanded the Nicaraguan Armed Forces.

“Through the military, a business network was set up that benefited the high command, who continue to participate in large businesses… they have large-scale companies and economic activities,” a source explains. La Prensa referred to Humberto as being “a general with refined tastes.”

Discontent increased with the outbreak of the civil war. Very soon, members of the disbanded Somoza-aligned National Guard banded together to form an extreme right-wing guerrilla movement that received financial support from the Reagan administration. The goal of the Contras was to overthrow the Sandinistas, who quickly organized their own military resistance.

It is said that Humberto Ortega was the main strategist behind said defense. He is generally blamed for imposing compulsory military service, which turned into a hunt for young people in Nicargua’s towns and neighborhoods. Many adolescents were forced to enlist in the army and were promptly turned into cannon fodder. Tens of thousands died in the civil war, which collapsed the economy, brutalized the country and resulted in the defeat of the FSLN.

Despite the defeat of the Sandinistas in the 1990 elections – with opposition leader Violeta Chamorro winning against Daniel Ortega – Humberto kept smiling and playing political chess. In exchange for a fairly orderly transition, the Sandinistas managed to keep him as head of the army, despite the discontent that this generated among the most conservative sectors of the National Opposition Union – the movement that brought Chamorro to power.

Anger over Humberto’s role caused fragmentation within the new government. Meanwhile, Washington pressured Chamorro to purge the elements of Sandinismo that were still in power. All of this tension – which spread like wildfire, largely due to the firewood that Ortega threw into the flames – put the Chamorro administration against the ropes. There was even talk of a possible coup d’état. Eventually, Chamorro affirmed that she would not allow herself to be “intimidated by any aggression” – she subsequently tightened restrictions around Ortega.

In 1990, the general was involved in a scandal that still haunts him. A Managua judge accused four of his bodyguards of participating in the murder of 16-year-old Jean Paul Genie. The boy was shot when he and a friend overtook Ortega’s convoy while it was driving through the capital. Jean Paul’s family has accused Ortega for the killing that shocked Nicaragua.

After a long period of negotiation, Humberto Ortega left the army leadership in 1995. Sources in Managua explain that his legacy was the establishment of an unwritten law that would ensure the peaceful transfer of power and institutional command within the Nicaraguan Armed Forces. Others, however, claim that during the Chamorro government, Ortega managed to consolidate an army that was loyal to the FSLN.

Since his retirement, the general has dedicated himself to the private sector, while also researching and writing on subjects that interest him. One of the questions that arises now – with his brother Daniel back in power and becoming an autocrat – is whether Humberto still wields enough influence within the Armed Forces to set himself up as a possible mediator in the difficult political crisis that Nicaragua is going through.

“The [generation] from his era is out of the army. His people – with whom he had a very close relationship – are no longer around. I don’t think Humberto Ortega has influence in the military,” says one of the sources consulted. Most of those interviewed for this report who live in Nicaragua have asked that their names not be used, for fear of retaliation from the government.

“[Humberto’s] influence is quite weak,” says Elvira Cuadra, an expert on security issues and the director of the Costa Rica-based Center for Transdisciplinary Studies of Central America. “He is seen as an authority figure… he’s been one of the most influential chiefs since the army was founded in 1979. But by now, there’s another generation of officers in charge of the army who are politically and personally distant from him,” she adds.

“He can play a role of influence within the circles of Sandinismo – the circles closest to [Daniel] Ortega. Humberto Ortega still has some influence with his brother, due to the family bond and his influence on historical Sandinismo. He’s a person who can play a role,” the analyst notes.

Humberto has tried to remain active in Nicaraguan political discussions through his books and columns. He often presents his own version of events, publishing with La Prensa, or even paying for media space to pour out his opinions. He has tried to sell himself as being different from his brother, with whom he has had strong disagreements.

One of these feuds occurred in 2005, with the death of their mother, Lidia Saavedra. Humberto arranged for his mother to be buried in a private cemetery in Managua, while his brother hoped to do so in the General Cemetery. “There were two hearse vehicles hired by each of the brothers to take the coffin,” reported La Prensa. In the end, Daniel prevailed, with then-Cardinal Miguel Obando y Bravo mediating.

Humberto Ortega has openly criticized his brother’s authoritarian drift. He has asked the president to release political prisoners and has reproached him for the fact that Hugo Torres – a Sandinista hero – died due to the “cruel confinement” to which he was subjected while incarcerated.

Daniel Ortega, meanwhile, has harshly attacked his brother in response, accusing him of becoming a “pawn” and “servant” of the oligarchy. It is because of these disagreements that the meeting between both men in Managua was disconcerting to many.

“He has always sought to have influence in the country,” says a source. “He has always seen himself as a great strategist. Humberto Ortega is a very controversial figure. There are people who say that he should be imprisoned for crimes against humanity and others who affirm that he can influence what remains of Sandinismo.”

In a country mired in the worst political crisis in its modern history, the retired general and millionaire businessman seems willing to remain active in politics. It is clear that he wishes to continue participating in Nicaragua’s never-ending game of power.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.