The Vatican Girl’s case reopens

A Netflix documentary and memoirs by a former papal secretary have pushed Pope Francis to review details of the disappearance of an employee’s daughter, missing for 39 years

Italy has long been the scene for the settling of scores in dubious business deals involving everything from the secret services to the Mafia, the Vatican, the Soviet Union and terrorist groups.

One such case is that of Emanuela Orlandi, daughter of a lay papal employee who lived within the Vatican. Emanuela disappeared on June 22, 1983, at the age of 15. Her family’s tireless efforts to uncover the truth have brought them face to face with both false leads and the indifference of the Holy See, which has always maintained that the investigation was Italy’s to carry out.

Now, a few months after the release of a four-part miniseries on Netflix called The Vatican Girl, together with the publication of the memoirs of the secretary to Pope Benedict XVI, Archbishop Georg Gänswein, Pope Francis has given the green light to a full Vatican investigation into a matter that has intrigued the Italian public for nearly 40 years.

Emanuela Orlandi disappeared from a street in Rome after leaving her flute class. There was a heatwave at the time and John Paul II had just landed in Poland, a hugely symbolic trip in the Pontiff’s fight against communism –one focused particularly on his country of origin. Emanuela, whose family had served seven different popes, called home before she disappeared, explaining that a man had approached her and offered her a job handing out flyers for the Avon cosmetics firm. She was to be paid the unlikely sum of 375,000 lire [about $200 today]. At 7pm, she failed to turn up to meet her sister. When the Vatican closed its doors at midnight, she had still not returned and, in fact, never would.

With the most powerful Communist Party this side of the Iron Curtain, Italy was at the time the final frontier between the West and the Soviet Union. Bullets were exchanged between the Red Brigades and Fascist squads. The P2 Masonic Lodge was at the center of all political intrigue and the Mafia had found the perfect vehicle to launder its money in the Banco Ambrosiano, which was run by the sinister Roberto Calvi – dubbed “God’s banker” due to his close association with the Holy See. In Rome, a criminal organization known as the Banda della Magliana controlled the streets. Its leader, Enrico Renatino De Pedis, a ruthless yet gentlemanly type, had favors owed to him by almost every member of the elite.

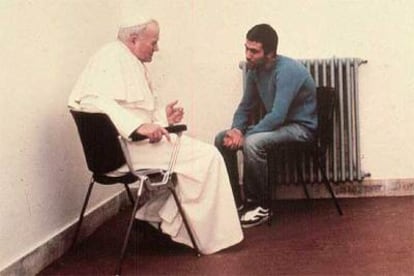

Curiously, Orlandi’s disappearance linked all these shady worlds. Even Ali Agca, the Turkish assassin who made an attempt on Pope John Paul II’s life in 1981, claimed to have information about her disappearance, publicly maintaining that she was kidnapped as a bargaining chip. The family’s lawyer, Laura Sgró, continues to believe that the key to solving the mystery of Emanuela’s disappearance lies within the Vatican walls. “The answers are in the Vatican,” she says. “We cannot be totally certain, but the absolute silence of the Holy See and the lack of cooperation only increase the feeling that this is so. I hope that now there will be a significant change.” Sgró added that a request made by lawmakers last month to establish a parliamentary commission of inquiry into the girl’s disappearance could have helped push the Vatican to act.

The family’s fruitless search for answers has been punctuated with people claiming to know what happened. One example was during the TV show Chi l’ha visto, a program similar to Who Knows Where; in 2005, an anonymous voice broke 14 years of silence, suggesting that those keen to find out what happened to Emanuela, must “look in De Pedis’ tomb.”

The leader of the Rome-based mafia, Banda della Magliana, De Pedis was a slick individual who spent lavishly on expensive suits and cars, De Pedis – aka Renatino – was tight with the rector of the small and secluded Basilica of St. Apollinaris, next to Piazza Navona, Monsignor Piero Vergari. When De Pedis was gunned down in Rome, Vergari recommended that he should be allowed to be buried in the crypt and the incongruous honor was accorded by Cardinal Ugo Poletti in exchange for a posthumous donation from his widow of the equivalent to a sum of just under $500,000. When forensics opened the tomb, they failed to find Emanuela’s remains among the bones.

The investigation changed radically with the testimony of Sabrina Minardi, a former prostitute from Trastevere, who had been Renatino’s lover. She explained that Renatino had kidnapped the girl, put her in his green BMW and kept her locked up in a house in the Rome neighborhood of Eur, before moving her to Monteverde. Weeks went by, until one day he asked Minardi to take Emanuela to the Vatican gas station, where a priest dressed in a cassock and a wide-brimmed hat picked her up and took her inside the Vatican in a black Mercedes with Vatican license plates. There is general consensus that this version of events is plausible. What happened next is less clear, but there are several theories based on police investigations. And they all involve the Vatican.

One version is political and suggests Emanuela was kidnapped to put pressure on the Vatican and Italy to release Agca, who was accusing the Soviet Union of being behind the attempted assassination of John Paul II, thereby endangering the geopolitical balance between the Soviet Union and the West. Building on this theory, it was mooted that Pope John Paul II had financed the Polish political movement, Solidarity, in a bid to contribute to the fall of communism, doing so with funds transferred from the Banco Ambrosiano to the Vatican bank – its main shareholder with a 20% stake. This money would have belonged to the Mafia, since the financial architect of the scheme had been Roberto Calvi. Just five days before the disappearance of Emanuela Orlandi, Calvi was found dead under Blackfriars Bridge in London with several bricks in his pockets as well as $10,000 and another $5,000 in lire, Swiss francs and pounds. The message to the Vatican and its bank president, Archbishop Paul Marcinkus, seemed clear: give us back the money or the girl will meet the same fate as Calvi.

De Pedis was thought to have pardoned the debt, hence both his resting place and his murder by his former colleagues. “Of course, they intervened,” said Andrea Purgatori, a veteran journalist who worked for the Corriere della Sera newspaper and features in the Netflix documentary. “De Pedis was buried in a crypt where not even cardinals were buried. And everyone knew he was a criminal. Why give him that right? Because he did favors for the Vatican and many prelates. There was a very concrete relationship that was later talked about by members of the gang.”

Purgatori believes that Orlandi was used as a bargaining chip in the financial exchange: “What I was told at the time is that the ‘Ndrangheta [the Calabrian mafia] lost €130 million with the operations of the Vatican bank at that time. But they probably didn’t get their hands on it, despite using Orlandi. In a kidnapping, the key element is proof that the victim is alive, something which was never given in this case. It is likely that she died hours after being kidnapped.”

A third theory, put forward by the Netflix documentary, comes from a school friend of Emanuela’s, who has not spoken out until now. Without showing her face or giving her name, this witness states that Orlandi confessed to her a week before she disappeared that a prelate, who collaborated directly with John Paul II, had sexually assaulted her. While not making the connection at that time, she says that over the years she understood it could be the key to her disappearance.

The Vatican will now have to review all its files, including the secret dossiers that circulated for years. The problem, as the family’s lawyer points out, is that almost 40 years later, most of those involved have died. The advantage, on the other hand, is that with every one of their deaths, another witness decides to speak out.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.