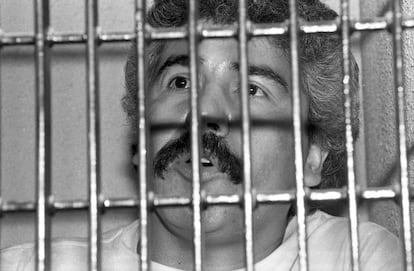

Rafael Caro Quintero: the historic head of the Sinaloa cartel is captured

Sources from the Marines confirm that the veteran narco, implicated in the murder of a DEA agent in the 1980s, was detained on Friday

Rafael Caro Quintero, the legendary narco leader of the 1980s, has been captured. Sources from the Marines confirmed to EL PAÍS that the former cartel leader, on whose head the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) had placed the highest ever reward for a criminal, was detained on Friday. One of the founders of the legendary Guadalajara cartel, which later became the Sinaloa cartel, was arrested for the second time near his home territory, in the Sinaloa highlands.

The criminal previously entered prison in 1985 after the brutal murder of undercover DEA agent Kiki Camarena. In 2013, still with 12 years of his sentence left to serve, he was released in Mexico after a state court concluded that he had been tried improperly. The United States pressured Mexican authorities to recapture him. The old drug capo, far from retirement, had a cartel named after him in northern Mexico. On Friday, at 69 years old, he returned to prison.

The narcotrafficker’s arrest came two days after the Washington meeting between Mexican president Andres Manuel López Obrador and Joe Biden. The agenda of the visit included security and weapons trafficking, as well as the migration crisis. The capo’s detention resolves one of Mexico’s long-standing debts to the United States. He is no longer the powerful drug trafficker he once was, but an October FBI alert indicated that he remained a threat. The door is open for a possible extradition to the United States, as happened with one of the formerly most-wanted drug capos, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, who was extradited to New York shortly after Donald Trump took office in 2017.

Caro Quintero previously served 28 years in a Jalisco prison. When 12 years of his sentence remained, a federal judge freed him because of a jurisprudential error. The brutal murder of Kiki Camarena in the 1980s destroyed the power that Mexican drug capos had accumulated over decades. The DEA’s persecution of the heads of the Guadalajara cartel sent them a firm message, and they were cornered for the first time. But none of them were extradited, and Mexican authorities did not stop Caro from being freed.

Caro Quintero has always been linked to the DEA’s thirst for vengeance. Few went so far as the founders of the Guadalajara cartel, Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo, the only one who remains in prison, Ernesto “Don Neto” Fonseca Carrillo; and Caro Quintero.

On February 7, 1985, as Camarena left the US consulate in Guadalajara, he was kidnapped by police and turned over to the Guadalajara cartel. At the time, they were the undisputed leaders of the Mexico-US drug trade. The American was tortured repeatedly, under the supervision of a doctor, on an estate belonging to the criminal group. When his body was recovered, it was discovered that he had been castrated and buried alive.

In 2013, an error in a sentence gave Caro Quintero his freedom. Before the justice system could change the ruling, the capo had already gone underground. From his hideout, he gave an interview to the magazine Proceso, denying his participation in Camarena’s death and affirming that “I’m no longer a danger to society. I don’t want to know anything about narcotrafficking. If I did anything wrong, I already paid for it.”

Despite being the criminal with the highest reward offered by the DEA, at 20 million dollars, his hiding spot was an open secret in his home territory. He remained near the small, remote villages where he grew up, the dusty sierra of Sinaloa and the desert of northern Sonora. This Friday, he was captured just 200 kilometers from there, in a town close to the Sinaloa mountains.

Returning home has been a strategy for Mexican narcotraffickers for decades, even when it led to their capture. Joaquín El Chapo Guzmán was last captured in a house in Los Mochis, Sinaloa, in 2016. It is assumed that the last free narco from the old-school Sinaloa cartel, Ismael El Mayo Zambada, has done the same. When Caro Quintero was freed, the first thing he did was to return to his hometown. He reorganized his people, negotiated a piece of the pie and continued quietly with business. The FBI located him in Badiraguato, Sinaloa, the hometown of nearly all Mexico’s drug capos, announcing that he was operating his own cartel out of the region. They were not far off the mark.

Caro Quintero’s name had also begun to sound in the municipality of Caborca, Sonora, which has been besieged by violence between local cartels for over a year. Some recall the arrival of Caro Quintero’s family to the Sonoran desert town in the eighties. A reporter who worked in the area for more than two decades recalls an image from a time before the streets were even paved: a pink limousine. “Caro brought a lot of money to the town. The people hold him and his family in high regard. Many still live here, and it is known that he comes and goes in this part of Sinaloa,” she said in a phone interview.

In Caborca, 100 kilometers from the US border and with little control from the authorities, Caro Quintero maintains another of his shelters. Recent narcomantas have indicated the presence of his gunmen in this area, and some local media note that his men have been involved in local territorial disputes.

Mexican intelligence leaked to the local press that, while in prison, Caro Quintero worked in coordination with the Juárez cartel to recover areas of Sonora that had taken over a cell of the Sinaloa cartel. Among them were envoys of one of the factions of the powerful cartel, the sons of El Chapo, known as Los Chapitos.

Northern Sonora remains under siege due to the war between Los Chapitos and local gangs who use the name of Caro Quintero. The newcomers have unleashed terror in the region due to their new, bloodier ways of intimidating their rivals. Meanwhile, the old capo continues to represent the golden age of drug trafficking.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.