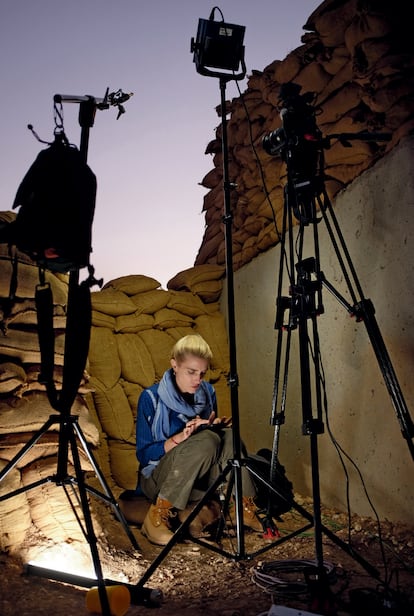

Clarissa Ward, war correspondent: ‘I faked having a fiancé because it made life easier’

The CNN journalist who reported on the fall of Kabul talks to EL PAÍS about her memoir, ‘On All Fronts,’ which addresses the challenges and highlights of her line of work

Clarissa Ward found out what she wanted to be while smoking a joint as a teenager. She was “high as a kite” and in the bathroom of her friend’s house when she understood: “I am not going to write novels or make films or be a great artist. I’m a vessel. I can understand people and convey their ideas. I’m a communicator.”

It took a while for that epiphany to materialize. She grew up among the most privileged circles of New York and London, taking classes in ice skating, ballet and horse riding. Her father is a former investment banker and ex-member of Cambridge University’s rowing team, while her mother is an exclusive interior designer. By the time she was eight, she had had eight different nannies. Nothing indicated that decades later, she would be dressed in an abaya, riding a motorcycle with Syrian fighters and trying to flee a shooting in an area where one day later American journalist Marie Colvin was killed.

After more than a decade working for TV channels such as Fox, ABC and CBS, Ward is currently the chief international correspondent for CNN. As a correspondent, she has reported from Iraq, Lebanon and Yemen. She has lived in Moscow and Beijing, and covered the uprising in Ukraine, the Russian military offensive in Georgia and even the tsunami in Japan. But it was her coverage of the fall of Kabul last summer that brought her worldwide fame. It’s a topic she covers in On All Fronts, a memoir that examines her experiences as a correspondent in a complex and changing world, as well as more the personal and surprising details of her life, such as the fact that she was Uma Thurman’s stand-in in the movie Kill Bill.

After returning from Ukraine, Ward talks to EL PAÍS about her memoirs via Zoom from her home in London. On the day before the call, Al Jazeera journalist Shireen Abu Akleh was killed by Israeli forces in Jenin, a Palestinian city in the northern West Bank. “It’s a tragedy. I didn’t know her personally, but of course, I know of her. I can’t say that journalism has become more dangerous, although I will say that more and more of my colleagues and friends have lost their lives covering conflicts.”

Question. How did a young, privileged woman who studied comparative literature at Yale become a war correspondent?

Answer. For me, it was 9/11 [terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center]. It rocked my world and just turned everything upside down. It made me realize that there was so much going on in the world that I hadn’t really been paying attention to. And I just became convinced right away that this is what I wanted to do, that I wanted to go to the tip of the spear and understand why these things were happening and who was responsible. I wanted to investigate why what we think about ourselves in America is different from what people see about us.

Q. You write in your book that the “privilege of witnessing history has a price.” What is the price?

A. Bearing witness to trauma can be traumatic in and of itself. There can be the risk of losing loved ones, losing colleagues, watching people die, watching children being injured or killed. And then you have to navigate the normal, real world and move between these two different universes in a way that doesn’t make you crazy. And you must find peace, which is a struggle.

Q. Susan Sontag wrote about the horror of returning to Berlin following the Balkan War and seeing the rest of Europe go on as if the siege of Sarajevo hadn’t happened. What defense mechanisms do you have to find peace and prevent trauma?

A. It’s my children. Before, I would often feel detached from my life when I came home. With children, in my experience, it’s not possible for me to feel detached. So no matter how exhausted I am, no matter how depressed I am, I see my children, I squeeze them, and there’s just this wellspring of love that is like a geyser. You can’t control it, you can’t squash it. It’s just there and it’s beautiful and it’s real. And it’s very physical.

Q. In your memoir, you speak about feeling guilty about leaving your children at home and catching a plane to report from a conflict zone. Male correspondents don’t seem to talk about this sense of “guilt.” Do they feel it differently?

A. It’s hard to know. Do they not feel it the same way or do they just not talk about it? I suspect that a lot of them just don’t talk about it.

Q. Do you feel different because you are a mother and a reporter?

A. I think it’s harder. For so long, we have told young women, you can have it all. You can have a great career and be a mother. And the reality is you can’t have it all at the same time. It’s constantly like a push-pull. If you’re excelling in your career, you’re feeling horrendous guilt as a parent. If you’re being a wonderful parent, it’s like you’re not present at your job. And it’s not just about covering war. I think professional women who are mothers as well feel this across the board.

Q. In On All Fronts, you write about yelling: “You’re a fucking moron!” to a condescending security advisor named Matt who “didn’t like working with women.” Have you come across many men like this in your work?

A. I think there are fewer than before, but they understand that they need to be much more careful about what they say out loud and how they deal with women. I do think that casual misogyny still exists. But it is not quite as pervasive and quite as offensive as it used to be. And that’s partly because there are many more women doing this job and just more generally because as a culture, we are constantly learning from our past about the ways in which we talk about women, treat women and view women.

Q. Has there been a change in the paradigm about how female reporters should be treated?

A. Yes, definitely. When I was starting out my career, you would often find yourself as a young, attractive woman in situations where you were having to be charming, but also laugh something off, but kind of make it clear. It’s tedious, it’s boring, it’s wasting my time, it’s awkward. Let’s just focus on the work. It’s not that I’m against romance in the workplace. If two people have a profound connection, fine. But I’m really glad we don’t have to deal with the constant, weird flirtation anymore because it was tedious.

Q. In your book, you write about being sexually harassed by Saif Gadafi, the son of Libyan leader Muammar el Gadafi. What made you decide to include this story?

A. First of all, I think I assumed I was never going to get an interview with him because it looked like he was dead. Now it turns out he’s not dead. So I’m still probably not going get that interview [laughing]. I included it because he never said it was off the record and the way he behaved was so disgraceful. I wasn’t traumatized by it at all. But the arrogance to assume that because of who you are that every woman really desperately wants you to make advances on her without even consulting her is deeply dangerous on many levels.

Q. You write that you spat in his face while he rubbed your leg.

A. Yes, it speaks to the problem of how power corrupts people’s minds. It’s not just an episode about a sort of famous son of a dictator trying to grope a young journalist in the back of a car. It’s the story of how people with too much power will freely exploit and take advantage of those who are more vulnerable than they are without giving it a second thought.

Q. You say that lipstick is a distraction, but Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci considered it a powerful ally.

A. It’s tricky. Over the years, I have come up with a uniform, and it’s what I will always wear in a conflict zone. I do wear makeup. If I didn’t, the viewer would be like: ‘We’re never watching CNN again.’ But the goal is not to look sexy or beautiful. The goal is to look polished and put together. And the goal is to have my appearance not be a distraction one way or the other. So you’re just like that’s Clarissa, the same way she always looks. I think when you wear a low-cut top or your hair down, you are almost distracting from the story that you’re trying to tell. I want you to focus on the story and not on my hair.

Q. When it comes to how women dress and gender freedoms, you write that there is a cultural divide between the West and the East. Is it difficult to navigate these two worlds?

A. It’s really complicated. And I think one of the most important lessons you learn as a journalist early on is not to assume that your way is the best way, that you are the most enlightened, that your culture is the most open-minded. You’ll very quickly realize that other people have a totally different understanding. We’ll be talking about freedom of speech and equality, about women can do this, and women can do that. And someone else will come back to you with: ‘What about prostitution and pornography?’ It’s a blurry line.

Q. In what sense?

A. Different cultures have their own norms, traditions and standards of beauty. You have to respect that. I think there is a difference, though, when you have women from within those cultures who are saying, like in Afghanistan right now, ‘I have been going to school and now I can’t.” If you know enough about Islam, you know that there is absolutely nothing in Islam that precludes women from going to school. Quite to the contrary, education is really encouraged for men and women. I think you can call that out as an injustice. But it is arrogant to make an assumption that wearing a headscarf is an injustice. That’s your preconceived notion. As a journalist, it’s not your place to weigh in on a lot of those types of debates. But when you see intolerance, corruption or discrimination, you call it out. That is the job.

Q. Many female correspondents wear a fake wedding ring to avoid being harassed. Is this something you had to do?

A. Before I was married, I definitely faked having a fiancé just because it made life easier. You tell people you have a fiancé and then they’re no longer going to bother you. I’ve definitely faked a fiancé. When I’ve gone undercover, I’ve had to fake a story about what I’m doing. When I went to Syria, I said that I was a decorator and trying to buy antiques. In general, though, you want to be as transparent as you possibly can be as a journalist because there are so many misconceptions about the work we do and the motivations behind it. But sometimes you throw in a white lie here or there to make people more comfortable.

Q. In On All Fronts, you write that a “good fixer can make the difference between a hellish assignment and a successful and enjoyable one.” You have the support of a team and your network, but there is a growing number of freelance journalists who have little support and are often poorly paid. Is the industry failing them?

A. I think the industry is more accessible than it was before. In the US, for example, there were three television networks. Now even The New York Times does great video projects. It’s completely changed the landscape of how we tell stories and who tells those stories. It also means that there are a lot more jobs out there. There are a lot more freelancers out there. And for the most part, I think that’s a good thing. But we as an industry have a responsibility to our freelance colleagues. We have to ensure that they have the appropriate training, that they have the appropriate body armor, that they are working with responsible editors who uphold them to the same security protocols that they would hold their own direct employees. I think in Syria, we saw too many instances of freelance journalists getting in over their heads and not having anyone telling them that they needed to put on the brakes. It’s about finding that balance.

Q. Your reports on the fall of Kabul on Twitter had a big impact worldwide. What is your relationship with social media?

A. It’s love, hate. Social media has allowed stories to be told in a much more democratic way, because they’re not only being told by people like me, they’re being told by women in Afghanistan, they’re being told by people all over the world. That’s really important. It is, however, often a pool of misinformation, name-calling, trolling, anger and ugliness. I think you can only use it if you’re strong enough, by which I mean, you have to be willing to tune out the noise and honestly, not just the criticism, but also the praise. Both of those things can be a distraction. Both of them can consume you for hours on end. That’s a waste of your time. Focus on the work.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.