From Borges to Jennifer Aniston: Science begins to illuminate the mysteries of memory

How do cell phones affect our memories? What percentage of them are imagined? A group of neuroscientists is trying to unravel the secrets of one of the brain’s most common and least understood functions

Remembering was his curse. In Funes the Memorious, Jorge Luis Borges tells the story of a Uruguayan gaucho who, after a riding accident, develops an extraordinary memory. Funes could learn languages and recite books from memory. Recalling a single day took him an entire day, as every detail accumulated itself in his mind in its most meticulous insignificance. The poor wretch saw this as a gift, but as his story unfolds, it reveals itself more as a curse, for remembering in such detail prevented him from distinguishing the essential from the superfluous.

Forgetting is also important in the formation of memory. This is what Borges explained through literature, and what the neuroscientist Charan Ranganath details with data in his book, Why We Remember. “The brain is programmed to forget,” he explains in an interview with this newspaper. “There are so many reasons for doing so that it’s truly a miracle we can remember anything at all.” The scientific study of memory often focuses on how we learn, how short-term memories are consolidated into indelible ones. Less attention is paid to the important capacity to generalize and forget — to how our brain discards less relevant information.

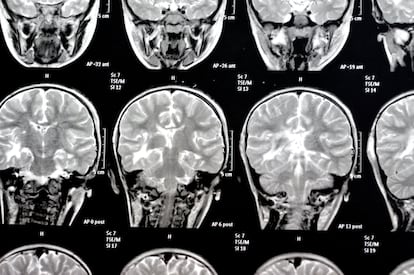

Ranganath is a pioneer in the use of MRI to study how we remember past events. And he has found that we do so in a constantly changing way. Our present somehow modifies how we interpret our past. “Every time we recall an event, we see it from our current perspective,” he points out. “So, for example, if you were to recall a recent breakup, you would evoke it very differently than if you were to recall it many years later. The same memory of a traumatic event can be presented as a story of survival and courage,” he notes.

Forgetting and the distortion of lived experiences are filters through which reality passes before being recorded in our memory. Furthermore, memories are not unalterable and faithful recordings of reality. Memory is fickle and ever-changing; it updates itself over time. “Every time you recall a complex event, the act of recalling it can alter the memory,” Ranganath points out. “Some parts of it may be strengthened, others weakened, and new errors may be introduced.” When you retrieve a memory, it’s not as if you’re taking a pre-written book from the library of your mind; rather, it’s as if you’re rewriting it. Memory is reconstructive. This would explain, only in part, an interesting paradox often mentioned by Nobel laureate Francis Crick, one of the discoverers of the DNA double helix: how is it possible that we retain memories for a lifetime while the molecules that store them die after a few hours, days, or at most, months?

The neuroscientist Rodrigo Quian Quiroga linked the story of Funes the Memorious with the latest research on memory in his book, Borges and Memory. Funes remembered everything with heartbreaking detail, but was incapable of grasping abstract ideas. Quian Quiroga discovered neurons in the human brain that respond to abstract concepts but ignore particular details. He called them Jennifer Aniston neurons, after the actress from Friends. In his research, the neuroscientist noticed how a specific neural network lit up in a patient with epilepsy when he saw an image of the actress, but also when he saw her name.

The experiment demonstrated that there are neurons in the hippocampus, a key brain region for memory, that respond to concepts and associations. They are the skeleton of memory, the foundation that allows us to record some of our experiences in a process that relies heavily on imagination and less on faithfully reproducing reality.

Funes’s misfortune began when he fell from a horse. HM’s began when he fell from his bicycle. It was 1936, and he suffered brain damage that led to severe epileptic seizures. A doctor considered removing his hippocampus as a cure, but the surgical injury resulted in severe anterograde amnesia. HM was unable to form new long-term memories. He didn’t recognize people he had just met, and he couldn’t acquire new skills or knowledge. He was nine years old and remained so until his death at 82. He lived anchored in an increasingly distant past. He didn’t learn anything new because he had nowhere to store that knowledge. HM became the most studied patient in the history of neurology; his analysis over decades revealed the crucial role of the hippocampus in memory consolidation and skill learning. His name was only revealed after his death in 2008. It was Henry Molaison.

Kepa Paz-Alonso leads the research group at the Basque Center on Cognition, Brain and Language. For decades, he has used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to observe how and where the brain lights up when people are remembering. He explains: “If you recall an experience many times, it becomes crystallized in the brain. When this happens, a new synapse is formed. And that is the beginning of a memory.” A synapse is the process of communication between neurons; it is the nerve impulse by which neurotransmitters jump from one neuron to another, carrying certain information.

The expert distinguishes between two types of long-term memory: episodic and semantic. The latter encompasses “our knowledge of the world,” he explains. It’s a memory of facts and concepts. On the other hand, there’s explanatory memory, which includes more personal experiences.

To explain the difference between the two, it’s helpful to revisit the story of another amnesic patient. In 1985, the psychologist Endel Tulving described the case of N.N., a man with a peculiar characteristic. He was perfectly capable of memorizing a series of random numbers. He possessed semantic memory, the ability to recall abstract information. The problem lay in his episodic memory: he couldn’t recall personal experiences. Tulving wrote: “N.N.’s knowledge of his past seems to have the same impersonal character as his knowledge of the rest of the world.” It was as intimate as a Wikipedia biography: a collection of abstract facts. He couldn’t remember the details of any event he had personally experienced: a birthday party, a romance, a vacation… His past was a series of data devoid of value or emotion.

The central point of Tulving’s study was the dissociation between semantic and episodic memory. But there is another element of N.N.’s pathology that is also worth analyzing: he was incapable of imagining his future. Tulving would ask him, “What will you do tomorrow?” and he could answer nothing beyond “I don’t know.” He would press him to ask where he saw himself in a year or 10 years, and he couldn’t venture a guess. This suggested the idea (later confirmed by neuroimaging studies) that the ability to remember, like the ability to project, comes from the same place: the imagination. Or, as Saint Augustine said in his autobiography, “the past and the future exist only in the soul.”

But why do we retain vivid memories of some events and not others? Not all memories are processed in the same way in our brains. Where were you when 9/11 happened? What were you doing minutes before you were fired from your job, when your partner proposed marriage, or you were informed about the death of a family member? Most people could answer these questions in great detail. “In our daily lives, important moments don’t happen in isolation,” the expert points out. “They are part of a flow of everyday experiences.” His team demonstrated, through 10 experiments, that significant events affected nearby neutral memories. They make us imprint them strongly. And so our brains are filled with seemingly banal memories, mere contextual fluff.

But in this whole process, we are not merely passive agents, the expert explains. There is some room for willpower. “We can’t guarantee it will last forever, but we can tip the scales. Paying close attention, attributing personal meaning to it, reliving the event shortly afterward (by talking about it or writing it down in a journal), and getting enough sleep all help,” he points out. To that end, one of the things we should do is put away our cell phones. Technology is affecting how we experience the present and will modify how we remember it in the future.

Since the advent of cell phones and the rise of social media, many people have become obsessed with documenting experiences and have stopped truly living them. These are the people who record a concert instead of dancing to the music, who photograph a sunset instead of observing it, who go on vacation and capture it on their phone, creating a filter between reality and themselves. By trying to record every moment, they stop focusing on the experience in enough detail to form distinctive memories that can be retained. They amass tons of videos and photos, preserving an exact replica of the past, like a 21st-century Funes. But like him, they are incapable of experiencing what is truly important and discarding what is superfluous.

“We’re increasingly outsourcing information to phones and the cloud, which may reduce the pressure to thoroughly encode some things, but we’re also constantly revisiting photos and messages that can reactivate and reshape memories,” Reinhart reflects. “The pattern of what we review — and therefore what becomes stabilized — might be changing because of this. I think this would be a very interesting and valid question, and it should be studied in real-world settings.”

While this is happening, various experts are trying to unravel the mysteries of memory, one of the most commonplace, yet also most unknown, processes that occur in our brains. It may be more of a philosophical than a scientific idea, but memories, in a way, tell us who we are. Who we were. How we understand and narrate ourselves. “We construct our identity from the specific subset of experiences that the brain has chosen to retain and highlight, so changing the memories that become stabilized can change the story we tell ourselves,” Reinhart summarizes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.