‘Travelers to Unimaginable Lands’: A first-person investigation into how a healthy brain reacts to one with Alzheimer’s

Clinical psychologist Dasha Kiper reflects on the ethical and vital challenges faced by caregivers who accompany family members suffering from dementia

For a long year, my father’s health has been failing. He is now increasingly dependent on my mother, who will soon turn 80. Without having to think about it, she has accepted that he is her life’s priority. Taking him to the doctor, going to buy medicine, rescheduling visits because he doesn’t feel like leaving the house, monitoring his diet. Anything she has to do, anything she can do, because she said so: in sickness and in health. And so it will be until the end. He can only use his strength to survive as best as he can, but my father sees it, he knows, he reiterates it to us, his children, and thanks her. I couldn’t stop thinking about the depth of that gratitude as I read, fascinated, Travelers to Unimaginable Lands.

Its author is Dasha Kiper, a medical professional dedicated to accompanying caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s. The men and women of all ages with whom this clinical psychologist works, whose cases are presented in each chapter, love those they look after, but their grandparents, their parents, their partners cannot be aware of the exhausting, maddening challenge they pose for those who are devoting their lives to them. While the caregivers can certainly sense the stress that dementia patients feel, the patients with dementia are rarely able to get a sense of what their caregivers are experiencing, writes Kiper. The unease caused by this imbalance is the subject of a book of admirable sensitivity and intelligence.

Why argue with the patient, if the person suffering from dementia can no longer listen to reason because their brain prevents them from doing so? This situation repeats itself over and over again. Even the author, when she was a caregiver, tried to contend with the lack of meaning in the actions of the patient with whom she was living. It was pointless. Or practically pointless. The next day, again, the same situation. And the next, and the next. No one can escape that mistake. Why, even though it is counterproductive and creates situations of sadness and chaos, does there seem to be no way to avoid it? Few moments are as dramatic as that of the son, Peter, who has to shower a mother, Mary, who because of her illness neglects her hygiene, which has caused infections. He tricks her into getting naked; she not only doesn’t understand him, but almost accuses him of wanting to abuse her, or humiliates him mercilessly. Devastated, Peter falls to the ground, screams, cries, breaks his own glasses and cuts his hands. “What the hell are you doing?” Mary asks, bewildered.

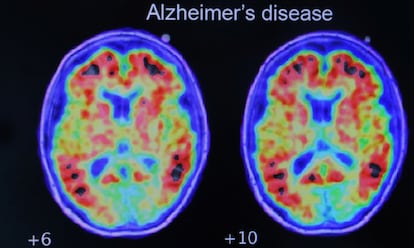

The key to the book, which transcends the discipline to become a work that reflects on the evolution of people and the way the relationship with others develops throughout life, is to discover the complex territory in which the disease absorbs the personality (“at what point does one self end and another begin?”), a process for which the healthy brain is not prepared. That is the imbalance for which there is no alternative, and Kiper, following in the footsteps of Oliver Sacks, contemplates it through her experience in the clinic, thanks to the best research, ultimately offering us a true life lesson.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.