Vox leader in Madrid faces new accusations in real estate scandal

According to a document seen by EL PAÍS, Rocío Monasterio signed her name as an architect five years before she completed her degree

The leader of the Madrid branch of Spain’s far-right party Vox, Rocío Monasterio, signed her name as an architect on a building certificate in 2004, five years before she completed her degree. That’s according to a document to which EL PAÍS has had access. This is the latest case in a deepening scandal over the projects Monasterio carried out as the head of an architect studio when she herself was not a registered architect.

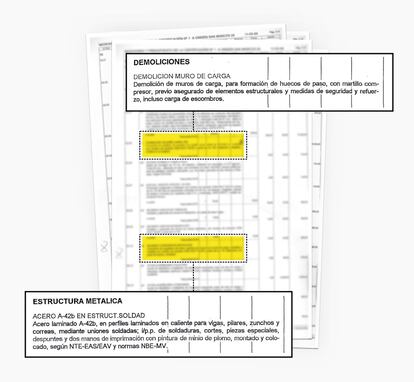

In this case, the building certificate was for a project on a store at number 24 San Marcos street, in Madrid. By signing the document, which was published by the Spanish news site El Diario on Monday, Monasterio took responsibility for complex work that could only be authorized by an architect, including tearing down load-bearing walls, the installation of steel beams and a metal structure, and pulling down and demolishing concrete supports.

It was a nightmare, she destroyed our lives. This woman is a danger to the public

Client of Rocío Monasterio

What’s more, Monasterio did not even have a building license to complete a project of this scale. Madrid City Hall had requested more information about the work, which was never provided. In the meantime, the project was completed in three months.

The property was an abandoned space in the center of Madrid that a company called Por Un Día S. L. was thinking of renting out to organize business events under its brand Versatile.

“We spoke with three architects who told us that nothing could be done, that they would never give us a license for use, because it was in an area with a lot of noise, with residents,” said Carolina D. P., the joint owner of the company. “But we spoke with Rocío Monasterio and she told us that there was no problem, that she had contacts in City Hall and would sort it out.”

The company knew of Monasterio from her interviews in several home and decoration magazines including Elle Deco, Nuevo Estilo and Habitania. In these interviews, she presented herself as an architect, although at the time she was still not a registered professional.

“She marketed herself very well, and she welcomed you in her studio, which was also her home – a spectacular loft that made you think that was exactly what you wanted,” said Carolina.

But the project on San Marcos street was “a complete mess,” according to Carolina. “There was a spiral staircase, which were banned years ago in evacuation areas, and she put an air conditioning unit in the neighborhood terrace. It made a lot of noise and the police came by every two or three days. It was a nightmare, she destroyed our lives. This woman is a danger to the public.”

Carolina and her business partner filed a complaint against Monasterio in 2006 to seek compensation but they lost their case in 2008.

This is the second time that documents have been found in which Monasterio appears as the architect before she completed her end-of-year project and registered with COAM, the official architects’ association of Madrid, in 2009. The first case, which was revealed by EL PAÍS, took place in 2003 when she signed her name on building plans for three lofts on Villafranca street in Madrid. At a press conference on Monday, Monasterio claimed that she could not “recollect when I was or wasn’t an architect.” A further three cases of irregularities – including the construction of her own home – have been uncovered involving Monasterio and her husband, Iván Espinosa de los Monteros, who is the spokesperson for Vox in Congress.

English version by Melissa Kitson.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.