Chinese, the new ‘in’ language at Madrid’s private schools

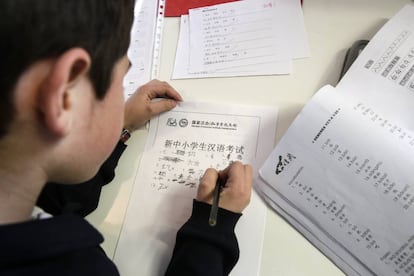

Mandarin is being taught at 89 centers while parents take on Chinese au pairs and send their children to summer camps in China to learn ‘the language of the future’

The parents of the young children studying Chinese at the Ya-Lan school in Pozuelo, outside Madrid, don’t understand a word of what is being said, but they beam as they listen to their offspring chanting the unfamiliar phrases.

It is not unlike the scenario they themselves were in 20 years ago, only then the language de rigueur back then was English. Now, they smile and clap as they watch their little treasures – some as young as three – sing the Five Fingers song, a typical Chinese nursery rhyme.

These are children from private and state-subsidized schools who already have a relatively good grasp of English. Their parents have signed them up because they consider that the best investment for their future is fluency in the world’s top three languages.

“This is the best gift we can give them,” says Manuela Hidalgo, a bank employee who has her five- and seven-year-olds at the academy.

Hidalgo recognizes the effort involved but believes it to be worthwhile. “It’s the language of the future,” she says, a phrase that is repeated like a mantra by all the other parents.

Classes in Mandarin have soared in Madrid in direct proportion to China’s economic clout. Just 10 years back, it was unusual to find Mandarin being taught in private and state-subsidized schools, but now 89 of them have it as an option and some have even made it mandatory, according to Hanban, the Chinese government’s promotional agency for language.

Chinese is now replacing French and German as a second foreign language in the schools around Madrid

Since learning Chinese is no easy task, some parents take an intensive approach and hire private tutors, and even live-in au pairs, to boost their children’s fluency. There has also been a rash of companies promoting summer camps in China with the promise of 100% immersion.

And as universities and international companies increasingly rate the skill, more people are coming round to the idea, says Nestor Tsai, director of the Association of Chinese Teachers, though the phenomenon is particularly popular with the wealthier sections of society, as many have had first-hand experience of what is happening in the US and the UK where Chinese forms an integral part of educating the elite.

“Many of these children will be the future leaders of Spain, the ones that head the multinationals and lead diplomacy,” says Tsai.

Ya-Lan Chuang, the director of the Chinese academy, started giving private classes to two or three children in 2009, not long after arriving in Spain from Taiwan. She now employs 11 native speakers who teach 25 afternoon groups in prosperous areas of Madrid, such as La Moraleja, Aravaca, Pozuelo and Serrano. Her method involves absorbing the language as though it were the children’s mother tongue.

Ya-Lan has no need to promote the academy as demand is overwhelming. People hear that their neighbor’s child is learning Chinese and they promptly sign their own child up. “It’s word of mouth,” she says.

Chinese is now replacing French and German as a second foreign language in the schools around Madrid. Five years ago, Hanban signed an agreement with the Madrid regional government, offering Chinese teachers to public schools free of charge as an extra-curricular activity, but so far only 34 schools have taken advantage of the scheme, according to Li Zhang, the Hanban representative in Spain.

Zhang says that the governments of other countries have been pushing Chinese. In 2013, former UK Prime Minister David Cameron encouraged schools to exchange French for Chinese and, according to Hanban, the UK now has more than 100,000 students of Mandarin, almost double the numbers in Spain which are estimated at 52,000.

But it is the under-18 age bracket that is really driving the boom. In private schools such as the Colegio Internacional Nuevo Centro, students have to take Mandarin from kindergarten through to baccalaureate. According to Li Shy Yi, head of the Chinese language department at Nuevo Centro, they were the pioneers – the first to make Mandarin part of the school curriculum.

Li Shy Yi had reservations at first, as there were not even any text books to work with, but the scheme has been an unequivocal success and over the years she has watched dozens of other schools in the region follow suit. “Chinese is one of the reasons that parents sign their children up to the school,” says Li.

But Chinese is so hard for a Spanish speaker that schools cannot promise parents that their children will come out with anything higher than level A1 – the most basic level in the European Framework of Reference for Languages.

Speaking like a native

Despite its rocketing popularity, few Spaniards have got a really good grasp of a language that is spoken by nearly a billion people as a mother tongue. “I only know half a dozen people in Madrid who speak fluently and can hold a conversation,” says Margaret Chen, president of the China Club Spain, an association that promotes exchanges between both countries.

The families who are spending the most on getting their children to learn Chinese also invest in summer camps in China. One company offering summer language camps is AbarcaChina, which charges €4,750 for three weeks and accepts students between the ages of 9 and 17. The price includes the flight, accommodation with a local family and daily Chinese classes. The director, Ana Abarca, believes there is a pressing need to learn Chinese. “We don’t yet realize the influence that China is about to have,” she says.

Many of these children will be the future leaders of Spain, the ones that head the multinationals and lead diplomacy

Nestor Tsai, Association of Chinese Teachers

Others opt for Chinese au pairs, a more economical route. According to the AuPair.com agency, in the first three months of this year they had 73 Chinese au pairs coming to Spain, five times more than last year during the same period.

Sofia Gahete, 14, talks with surprising fluency to her au pair, Xu Zichen aka Totó, 23, who is the fourth to live with Sofia’s family in Daganzo de Arriba.

Sofia says Chinese people are floored when they hear a European speaking their language fluently; when she upbraided a group of Chinese passengers in their own language for attempting to skip the check-in line on a flight to Dubai, mouths dropped.

Happy and outgoing, Sofia translates what Totó says into Spanish: “She says that a Chinese person could mistake me for a native speaker with a bit of an accent.”

Totó helps Sofia with her writing, which is even harder than speaking, with a view to Sofia taking the HSK 4 official exam this summer. This is a test that adults usually take after several years of study.

Both her parents, like so many others, believe that Chinese is going to be essential for the next generation, and her father José Gahete, a 50-year-old industrial engineer, says that while not everyone is keen on having someone come live with them for the whole year, they have been lucky because their daughter has always gotten along well with her au pairs. “Our experience has been great, and it’s preparing Sofia for the future,” he says.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.