“I once voted for the Communist Party, but it was phoney-baloney. Now I’m with Vox”

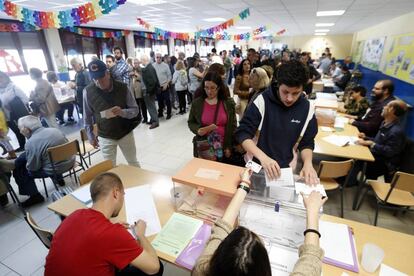

Spaniards of all ages and political stripes are flocking to the polls, convinced that this could be one of the most decisive elections the country has ever held

Florencia swoops into the polling station with her two fifty-something daughters in tow, looking marvelous at her 83 years of age. As soon as she walks through the door, she informs anyone who cares to listen: “I voted for [Communist Party leader Santiago] Carrillo back in the day, but it was all phoney-baloney. Now I’m with Vox.”

This brings tears of joy to the eyes of the Vox party representative at this polling station in Madrid’s Lavapiés neighborhood, where residents voted overwhelmingly for the anti-austerity party Podemos and the Socialist Party (PSOE) in 2016. He gives Florencia two loud kisses on her cheeks and says: “Spain thanks you for this.”

We need to have the same laws in Madrid and Andalusia

Miranda de Juan, Vox vote

Spaniards poured onto the streets on Sunday to determine their future. Rivers of people flowed towards polling stations with the intimate feeling that their vote could be decisive in such a divided and uncertain political scenario. Women could be heard telling someone on the other end of the line: “If you don’t go vote, don’t complain later.”

Marta and Hugo – two well-known actors, citizens later informed this reporter – are here moved by a sense of duty. While they are not quite as open as Florencia about their voting choices, one doesn’t exactly need to be Nostradamus to get a sense of where their sympathies lie. What they do admit is that they voted to prevent a right-wing bloc that includes the far-right Vox from taking power. “They’re going to get good results, but I hope they don’t govern. The left has been mobilized too, and I have the feeling that this is the time when there’s been the most talk about politics,” says Marta.

Juan Fernández, 67, is wearing a sailor’s cap made by his brother’s father-in-law, who happens to be a capmaker. If he doesn’t wear it, the sun hits his glasses and “I can’t see a damn.” He voted for the original Communist Party of Spain until it disappeared, then he switched to the Socialist Party (PSOE), which he remains faithful to. Juan is convinced that half of Spain is “fascist,” which is why the other 50% needs to contain it. Still, today’s choice has more to do with financial matters: “I’ll tell you bluntly: the PSOE has raised my pay by €115. Not bad.”

Just a few subway stops away, a different world awaits. At the last election in 2016, 80% of voters at the upscale neighborhood of Salamanca opted for the Popular Party (PP). But Noemí Boada, 60, believes that this is going to change because Vox is going to take a lot of votes away. She doesn’t have any preferences either way, but hopes both parties will reach a deal to defend “the interests and unity of Spain.”

Her daughter Inés, 24, openly says that she supports Vox leader Santiago Abascal, whom she describes as a person who defends “the dignity of individuals and respect between men and women.” Mother and daughter both see themselves as feminists but not “feminazis,” a term used by Vox to define so-called radical feminist groups. Inés’ own grandmother, they note, went on to be a scientific researcher “without the need for affirmative action or quotas.”

I have the feeling that this is the time when there’s been the most talk about politics

Marta, actress

Standing nearby are Paco and Juan, two Spaniards nostalgic for the days of former PP prime minister Mariano Rajoy. These friends explain that Rajoy represented deep, solid values in a society obsessed with youth and good looks. Both say they are voting for the PP not so much because they are enthused with the new party leader, Pablo Casado, but because they don’t like the newfangled ideas represented by Vox. “If you’re conservative, you’re conservative all the way: you don’t like uncertainty,” they say before heading out for beers.

Over in Chamberí, another Madrid neighborhood with a penchant for the PP but some sympathy for Ciudadanos as well, the De Juan siblings have embraced Vox instead. Marcos, 26, wants the gender violence law to be modified so it will be known as “intrafamily” violence and not exclusively protect women. His sister Miranda is sick and tired of the system of devolved powers to the regions. “We need to have the same laws in Madrid as in Andalusia,” she says. Both add that the government’s temporary suspension of home rule in Catalonia following the unilateral independence declaration of October 2017 was too “light,” and that the time has come for “the real thing.”

After voting, Marcos and Miranda leave for the the gym. The Spain that votes also has other important things to do.

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.