Spanish elections: a 1985 law for 21st-century communications

Despite bans on campaigning outside specific time periods, the popularity of social media apps make this rule very difficult to enforce

The Avenida de América station is one of the busiest in Madrid’s subway system. In recent days, commuters emerging from the Metro stop have been confronted by a large advertisement featuring a message from center-right political party Ciudadanos (Citizens), aimed at Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez: “Pedro, we are going to change Spain.” Above it, there was a quote from Sánchez’s new book Manual de Resistencia (or, Resistance Handbook) in which he recounts how his first decision upon becoming prime minister was to change the mattress in the bedroom of his new official residence, La Moncloa palace.

⚠ Sánchez denuncia a Cs por una valla que habla de su colchón y pide su retirada, pero no denuncian ni pide la retirada de las pancartas que dicen que España no es una democracia ni los lazos amarillos de sus socios Torra y Puigdemont.

— Ciudadanos 🇪🇸🇪🇺 (@CiudadanosCs) April 6, 2019

😉 Pronto, otra valla de respuesta pic.twitter.com/fmyPhEqiEx

“Sánchez reports Ciudadanos for a sign talking about his mattress, and demands it be taken down, but he neither reports, nor asks for the removal of, signs saying that Spain is not a democracy or the yellow ribbons of his partners Torra and Puigdemont. Expect another sign in response soon.”

The Madrid Electoral Board ordered this sign taken down after the governing Socialist Party (PSOE) claimed that the message violated election legislation, which states that such advertising is prohibited from the time that elections are called until the official start of the campaign race.

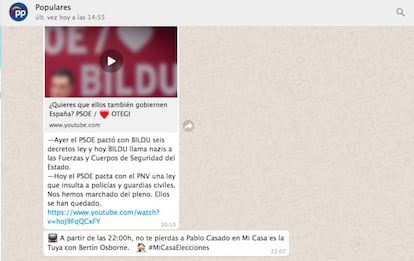

That decision was made on April 5. On the same day, political parties used the cellphone applications Telegram and WhatsApp to send messages to their followers. The Popular Party (PP), for instance, sent out a video with the title: “Do you want them to govern Spain as well? PSOE / ❤️ OTEGI.” The conservative party was alluding to Arnaldo Otegi, a historical leader of the Basque radical left who was once a member of the now-defunct terrorist group ETA and has served prison time for those activities. Otegi is currently the general coordinator of EH Bildu, one of the parties that supported Pedro Sánchez’s successful no-confidence motion against then-Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy of the PP in June of last year.

Meanwhile, the PSOE sent 18 messages to more than 3,200 subscribers of its official Telegram channel, discussing the PM’s address in Toledo and explaining the decisions made at the Cabinet meeting.

These were all direct messages of a political nature, sent out through official party channels on social media. In other words, these chat groups have become the virtual equivalent of the bricks-and-mortar buildings covered with campaign ads.

The law regulating campaign advertising was approved in 1985. “It was written with the public media outlets of the time in mind,” says Agustín Ruiz Robledo, a professor of Constitutional Law at Granada University.

Berta Barbet, a political scientist and researcher at Barcelona’s Autónoma University, adds that “when it was approved, the law was meant to give all parties similar opportunities.”

“Maybe not all parties could afford to run a six-month campaign, but they could afford 15 days. But we should reconsider how to enforce this in a world with so much information,” says Barbet.

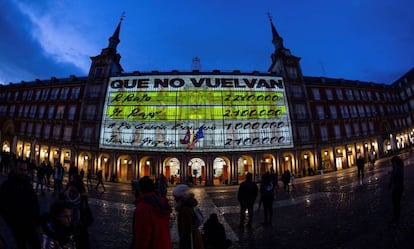

The PP also turned to the Madrid Electoral Board after the left-wing anti-austerity party Podemos projected images in Plaza Mayor on April 6 showing “the Bárcenas papers,” alluding to a major corruption scandal that has long plagued the conservative party. Under the heading “Que no vuelvan” (“Don’t let them come back”) the image showed a page from the ledgers of the former party treasurer Luis Bárcenas, allegedly detailing a cash payment made to former Prime Minister Rajoy.

Even though the law says nothing about social media, a party could not ask for votes through its social media accounts the day before the election

But what about the thousands of online messages that came along with these projected images, grouped under the hashtag #QueNoVuelvan? On Twitter alone, there were more than 71,000 messages with that tag on Sunday, according to the social media monitoring tool Digimind.

The old 1985 law does talk about political parties’ “digital media,” but when it comes to social networks it is not always easy to identify who is sending out a message. Behind the building ads, there is always a company that is paying and a signature that authorizes a budget outlay. But behind a viral WhatsApp post, all that is required is people who are willing to retweet your message.

“On one hand, you have the open social media such as Twitter or Facebook, where you cannot control the information that individuals move around, just like you cannot control people discussing politics on the street. But WhatsApp is a little harder, as you have no control over what gets said or shared, or who is doing it,” says Barbet.

The legal loophole

The 1985 law also contains other articles that conflict with the way we receive information these days: the ban on campaigning the day before the vote (officially a “day for reflection”) and the ban on publishing opinion polls a few days before voters go to vote. Both of these prohibitions are easy to get around through a Twitter account that can even be anonymous, or with chain messages.

“The general principles of the law can help us somewhat,” says Ruiz Robledo. “For example, even though the law says nothing about social media, a party could not ask for votes through its social media accounts the day before the election, as these would be considered just another medium.

“But then there are the messages from friends favoring one or another party. I don’t think this can be avoided,” he adds.

As a matter of fact, this is precisely the sort of communication that parties desire the most. With a general election coming up where 40% of potential voters are still undecided, according to the most recent poll, the opinions of friends and relatives become more influential than anything else, studies have shown.

As for the ban on publishing opinion polls, there are ways of getting around that. For years, an outlet called El Periódico de Andorra has been publishing the results of its surveys, and several Twitter accounts represent the parties using symbols rather than their actual names: the PSOE is a strawberry, the PP is a drop of water, Podemos is an eggplant and Ciudadanos is an orange.

The Barcelona professor sums up the contradictions: “The law is a bit paternalistic. The information is out there, it is more accessible than ever, and it cannot be stopped.”

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.