Frankenstein and eight-headed serpents: Spanish campaign takes on apocalyptic tones

As elections approach, the opposition is resorting to scare tactics to convince voters that Socialist Party Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez must go

In March 1996, the governing Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE) commissioned a campaign video that depicted its rival Popular Party (PP) as an enemy of progress, and illustrated the idea with ominous black-and-white images that included a large barking dog. The TV ad about “the Socialist doberman” made waves at the time, but these days it wouldn’t even scare kindergartners.

The Popular Party leader says that Sánchez is promoting “a social-engineering project”

In order to properly frighten people in these frenzied times, it appears necessary to resort to more fabulous figures than a mere hound. With a general election coming up on April 28, followed by local, regional and European polls on May 26, parties are turning to horror stories and even to Greek mythology in an attempt to strike fear into the hearts of voters.

The term “Frankenstein government” has already become commonplace, following last year’s successful no-confidence vote against the PP’s Mariano Rajoy. The motion was led by PSOE leader Pedro Sánchez with support from a loose coalition of leftist and regional parties, including Catalan separatists. This led critics to compare a hypothetical executive made up of all these varied groups with Mary Shelley’s famous patchwork monster.

And now comes “the eight-headed Hydra,” in the words of PP leader Pablo Casado, who used this figure from Greek mythology at a Barcelonarally on Monday, when he listed some the “heads” on this serpent-shaped monster: “Separatists, coup-plotters, terrorists, communists, Chavistas, Castro sympathizers...”

The fact that the PP leader chose the Catalan capital for his campaign program presentation was already an indication that there would be a lot of verbal artillery on display. And Casado, who took over the party presidency in July with a more conservative agenda than his predecessor Rajoy, did not let his supporters down. He even accused Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez of accepting “hands stained with blood,” alluding to EH-Bildu, a Basque party that grew out of the radical leftist movement that used to support the now-defunct terrorist group ETA.

Casado held that Sánchez is promoting “a social engineering project,” that his friends are “coup plotters” and “terrorists,” and that as a result he is “a public danger to Spain.”

Sánchez, who has been heading a minority government since the successful no-confidence vote, was forced to call a snap general election after failing to secure enough support for his budget plan earlier this year. His blueprint was also rejected by the Catalan separatists whom Casado accuses of attempting a coup against Spain with their unilateral independence declaration of October 2017.

Meanwhile Ciudadanos (Citizens), a center-right protest party that grew out of the economic crisis and has become one of the leading groups in parliament, is striking a somewhat less strident tone but still warning about the dangers ahead.

Party leader Albert Rivera, who is competing with Casado for right-of-center votes, said on Sunday that the need for Sánchez to be kicked out of office “is a national emergency.” Ciudadanos, which was originally founded as a Catalan non-nationalist party and opposes independence for the northeastern Spanish region, recently released a campaign video with a direct message for the prime minister: “Pedro, WE are not going to sell out Spain.” The video also shows three Catalan government leaders sitting in front of a telephone that doesn’t ring because the new PM, Albert Rivera, isn’t calling them.

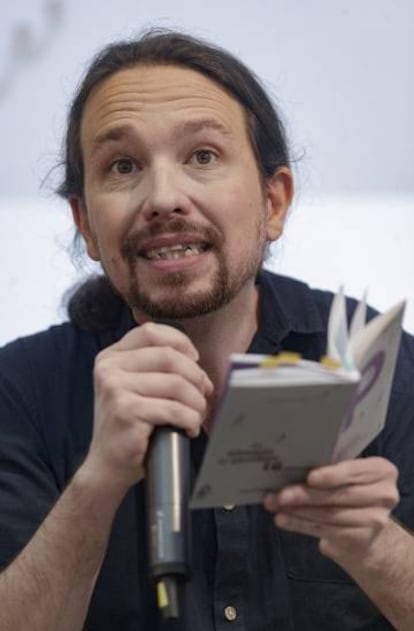

On the left of the political spectrum, the word “Catalonia” is mostly reserved for times when party leaders show up in the region. On Monday, for instance, Podemos chief Pablo Iglesias talked a lot about the Spanish Constitution at an event in Madrid, but never once mentioned the thorny Catalan issue.

Instead, he took a page out of the book of an old master, former United Left leader Julio Anguita, who used to brandish the Spanish Constitution and recite the passages about recognized social rights such as the right to a job and to housing. On Monday, Iglesias backed Unidas Podemos’ campaign platform with Article 128.1 of the highest law in Spain: “The entire wealth of the country in its different forms, irrespective of its ownership, is subordinate to the general interest.”

As for the governing PSOE, it is conducting a low-profile campaign with little desire for confrontation. Voting intention polls show the Socialists in the lead, but critics note that the party followed a similar strategy at last year’s regional elections in Andalusia, and the outcome was disastrous for the PSOE, which lost its 36-year hold on power to a PP-Ciudadanos coalition backed by Spain’s new far-right party, Vox. The latter is hoping to replicate this success at the upcoming elections, and polls show that its message is resonating with voters, a fact that has pushed the PP and Ciudadanos to ramp up their own rhetoric.

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.