Timeline of Julen tragedy: “A child has fallen down a small hole. He needs to be rescued”

EL PAÍS recounts the events following the disappearance of the two-year-old, who fell down a borehole in Málaga on January 13

At 1.57pm on Sunday, January 13, Málaga’s 112 emergency service center received a phone call. A woman told them: “A child has fallen down a small hole, around 40 centimeters in diameter. He needs to be rescued, the mother is crying and screaming.” The woman and her husband were hiking when they heard the screams from a rural property near Totálan, a town in Málaga in the west of Spain. The owner of the land and his wife, cousins of the child’s parents, were in a state of panic and had not called the emergency services, prompting the hikers to take the initiative.

There’s no other rescue like this known in the world, but we thought new problems, new solutions

Julián Moreno, technical director of the local firefighters, was with his family when he received the call from emergency services. He explains that the first team to arrive was from the Rincón de la Victoria municipality. “At the farm, the firemen found that there was in fact a borehole, and the information they were given was that this child could be in the borehole. The parents were very upset and when I arrived a little later, they had already been taken aside to a calmer area.”

Within half an hour, teams from all sectors of the emergency services had arrived on the scene, including firemen, Civil Protection personnel, and the Civil Guard’s specialist forces: the High Mountain Rescue Group (GREIM) and the Underwater Activities Specialist Group (GEAS).

Leading this improvised task force was Jesús Esteban, a colonel with five years experience as the head of the Civil Guard in Málaga who had previously worked as the head of Maritime Services in the Investigation and Operations Helicopter Unit.

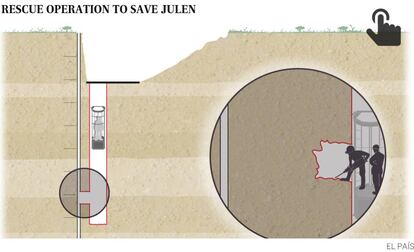

Each studied the borehole and came to the conclusion that the hiker was wrong: the borehole was not 40 centimeters wide, as she had guessed, it was only 25. Neither Esteban or other emergency personnel had seen anything like it before. It would be impossible for anyone to fit down there. To join an elite group known as the Asturian Miners Lifesaving Brigade, candidates must be able to squeeze down a 50-centimeter hole – but 25 was unthinkable. According to the parents of the child, Victoria García and José Roselló, their boy Julen was two years old and weighed just 11 kilos. Julen had fallen down a hole no one bigger than him could fit through.

“There’s no other rescue like this known in the world, but we thought new problems, new solutions,” said Moreno, the head of the firefighters. “We swore to ourselves. When we are going to do an emergency operation, we commit absolutely but in this case it was even more so because of the nature of the situation.” Between Sunday and Wednesday night, when he first spoke with EL PAÍS, Moreno had slept a total of six hours. By Saturday, six days after the first emergency call, he had slept just nine.

The first priority was finding out if Julen was okay. So on the first day of the incident, emergency services called the offices of Desatoros Pepe Núñez, a business specializing in cleaning and unclogging tubes, drains and pipes. “It was around 2.30pm and they told us a child had fallen down a borehole,” remembers Ana Núñez, one of the heads of the firm. “They told us the measurements of the hole and asked us if they could use our inspection equipment to find out how the child was. Our people arrived around 4pm.” The business uses robotic cameras and agreed to loan these to the emergency team.

“We always roll them down the pipes when they are horizontal, but because it was a vertical borehole, we took off the wheels and levered it down on ropes,” she explains. One of these cameras was lowered until it hit something. But it was not Julen; it was a blockage. What first appeared to be a difficult operation had turned into an even more complex situation. The borehole Julen fell down was not cladded, so when he fell, earth from the tunnel fell on top of him.

The first idea was to break up the blockage but this met with little success. A kind of spoon, tied to a base, was used to try to remove the earth and soften it so that it could be absorbed. This was an incredibly delicate process given it was not known whether Julen was just below the blockage. “The first idea is always to follow the same path as the child. The blockage was the first obstacle, so we tried to take it out of the way,” said one of the firemen.

Throughout the afternoon, as news began to spread of the incident, numerous businesses began to offer their services to help in the rescue operation, including the company SG from Cádiz, which said it had a sand-absorption truck that could be useful.

A kind of spoon, tied to a base, was used to try to remove the earth and soften it so that it could be absorbed

On Monday, the day after Julen fell in the borehole, the truck arrived to help – but there was a problem. The truck could not reach the farm because it was only accessible via a narrow track up a very high slope. For two hours an excavator worked to clear the path. When the truck was at last able to start working, it was only able to remove 30 centimeters of earth. It was slow and laborious work and the first signs of the problems that were going to complicate the rescue mission.

At that point, the team began preparing plans to bore two tunnels – one vertical and one horizontal, although the latter plan was eventually abandoned in favor of a second vertical tunnel. This would enable rescuers to reach below the blockage to where Julen was thought to be. Meanwhile, the robotic camera had still not found the child, but it had spotted the first physical proof he was down the hole: a bag of snacks and a cup that he had been carrying.

More things happened on Monday. In a tent, acting as a makeshift command center, the Civil Guard began to take statements from the family who were at the farm on Sunday, the hikers who helped them, the owner of the farm and the person who made the borehole.

Julen’s father José said he was looking after the toddler while the mother made a call to the hamburger restaurant where she worked. When José went to look for wood to make a fire for a paella, the boy ran away. Another member of the family, a woman, cried “the boy, the boy!” and chased after him. The father ran to catch up with him and when he was within 10 to 15 meters of reach, Julen disappeared down the borehole. The woman says José began removing stones from the edge of the hole and put his hand down in effort to grab his son, but as he did so the ground fell in. Julen was heard crying and then nothing more.

On Tuesday morning, Defense Minister Margarita Robles called on the Asturian Miners Lifesaving Brigade to join the rescue effort. A military plane picked up eight of the specialists and flew them to Málaga.

That same day, a man named Antonio García arrived in Totalán and identified himself as the person who had drilled the borehole. García, who runs Triben Drilling, a business with 40 years of experience and “no problems until now,” told the media: “I left the borehole sealed as I always do.” He said he had placed a rock over the hole and added that it measured only 21 centimeters across. Via a WhatsApp message to EL PAÍS, García argued the borehole, made to see if there was water, had been “modified and deepened.” The central government’s delegation in Málaga says the Civil Guard has taken no further statements since then but will continue the investigation once the rescue operation is over.

On Tuesday, doubts were raised on some Spanish TV shows about whether Julen was inside the borehole at all

On Tuesday, doubts were raised on some Spanish TV shows about whether Julen was inside the borehole at all. A builder who drills such holes told one network it was “virtually impossible” for him to be in there. The comments reached Julen’s father, who decided to speak with the local news daily Sur and hold a press conference on Wednesday. “I wish it was impossible for him to be in the borehole, as I have heard. I wish it was me buried there below and him up here with his mother,” José told the press. In 2017, Josè and his wife Victoria García lost their eldest child Oliver when he was three years old from a sudden heart attack.

The central government’s deputy delegate in Málaga, María Gámez and Colonel Juan Esteban, announced that day that “biological remains” – specifically a strand of Julen’s hair – found in the borehole confirmed that the toddler was trapped inside.

On Wednesday, José Antonio Berrocal, the president of the Andalusian Caving Federation, told the press that he was aware of cases similar to Julen’s where a person had survived up to 10 days by remaining asleep in a semi-conscious state, with minimal movement and less need for oxygen.

Children’s doctor Iván Carabaño from the 12 de Octubre Hospital in Madrid told EL PAÍS that Julen was in a “very complex and unusual situation,” which made it difficult to reach a prognosis. “The cold has two aspects,” he explained. “On the one hand, it’s negative because it can lead to many consequences for him. But in this case, we are all hoping for the best outcome: that it wins him time to survive, because at the low temperatures the metabolism of a human being slows down and tissues are preserved.”

But Carabaño says Julen is not helped by his low weight: “Aged just two there is a greater risk of hypoglycemia and it is more difficult to manage going without food.” This could drive the toddler to eat anything that he can find, he explained.

There are now around 300 rescuers in Totalán to help save Julen. The case has attracted the attention of media from across the world. Thousands of people have sent messages of support to the family, drawings for Julen and offers to help – many of the 700 residents in Totalán have offered their houses to the rescuers.

Meanwhile, work to drill a tunnel to reach Julen continues around the clock, regardless of the intermittent rain. Dozens of people have become emotionally involved with the plight to save the toddler, working tirelessly, with just a few hours of sleep and the hope of finding him alive.

“If we didn’t have hope we wouldn’t be able to work as we are, that’s why we keep believing,” explain Julián Moreno, the firefighter chief, who has kept up the optimistic message throughout the rescue mission, despite the many complications.

English version by Melissa Kitson.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.