How Twitter helped a Spanish octogenarian sell out his Civil War memoirs

Amateur writer Emilio Ortega had failed to sell a single copy of his book, until he met a young man who felt his story of hardship and survival deserved an audience

“My mother was a fighter, a truly courageous woman. I think that sensitive people who read my story will be moved,” says Emilio Ortega in a telephone conversation from his home in Almería.

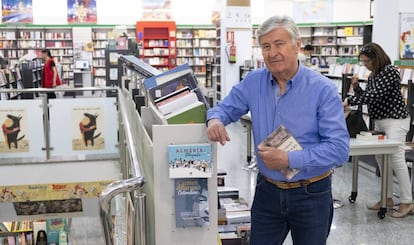

At the age of 81, Ortega’s life has been turned around by sudden and unexpected literary success – with the help of social media.

In January, this amateur writer self-published an autobiography called El mundo visto a los ochenta (or, The world viewed at 80), but it failed to sell a single copy at any of the city bookstores where it went on sale.

I don’t think my mother had a single moment of happiness

Emilio Ortega

Feeling downcast, he attended the Almería Book Fair in early May to see if he might find some buyers there. He did not. But he ended up giving a free copy of his book to a young man who expressed an interest in it. “I never thought that our conversation would take things this far,” he laughs.

Ortega, who has French citizenship and was born in Oran (Algeria) to Spanish parents, is living testimony to the hardships of the Spanish postwar era.

“My father was a lieutenant in the Republican Army, and he died in the Battle of the Ebro. Pepa, my mother, was left without a widow’s pension and was forced to beg to raise her children.”

The young man was so taken by Ortega’s story that he decided to share it on Twitter. The tweets quickly spread, and another user decided to buy a copy of the book. He was the first customer.

“Pedro and I talked, and he told me he would do whatever he could to make sure that more people heard about my memoirs,” says Ortega.

In the ensuing wave of solidarity, the book was sold out within a week across Almería. “We’ve ordered another print run of a thousand,” said a spokesperson at the publishing house, Círculo Rojo.

I don’t want to get rich off this, I am not a great writer

Emilio Ortega

In the first part of the book, Ortega recounts a childhood spent staving off starvation with his mother and cousin in Madrid, where they were forced to take up residence during the Civil War (1936-1939) due to his father’s military obligations.

“He was a lieutenant in the Republican Army, but he died in the Battle of the Ebro. Pepa, my mother, was left without a widow’s pension and was forced to beg to raise her children. We would resell the loaves of bread from the ration cards in order to make a few cents and buy peanuts or carob beans,” he recalls. His mother made an additional 12 pesetas a day as a house cleaner.

They lived in fear, and finally left the city. “Plainclothes police officers arrested my mother several times because begging was forbidden,” says Ortega.

They rode several trains as stowaways until they reached Zaragoza, where their belongings were stolen. “That’s despite the fact that my mother was carrying a picture of Our Lady of Carmel for protection,” jokes Ortega.

Nine years after the war ended, Franco opened up the borders and the family was able to return to Algeria with help from a relative. “I dropped out of school because I began an apprenticeship with a blacksmith,” he explains. Years went by, and Algeria became an independent country. Overnight, “there were a lot of dead people, especially white ones.”

Plainclothes police officers arrested my mother several times because begging was forbidden

Emilio Ortega

Ortega traveled to Paris, where he met his wife, who was originally from Almería in southern Spain. They had a child.

“Fortunately, my mother was always by my side, until she left us,” he says.

Nobody was expecting it. “She was admitted into hospital for an ulcer on her leg, but died from a bowel obstruction. I didn’t make it in time. She was a very unhappy woman; both her husbands died, and I don’t think she had a single moment of happiness.”

Ortega is grateful to the two young men who gave a voice to this story, which he had to type up four times on his computer because “it got deleted.”

Ortega feels that Spain is his home, and he wants to die in Almería. Before hanging up, he makes one final observation about his sudden success: “I don’t want to get rich off this, I am not a great writer, but I hope it will help others share their own experiences.”

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.