How tourist apartments are hurting Madrid’s neighborhoods

Platforms like Airbnb are pushing up the cost of rent and forcing locals to move out of the city center

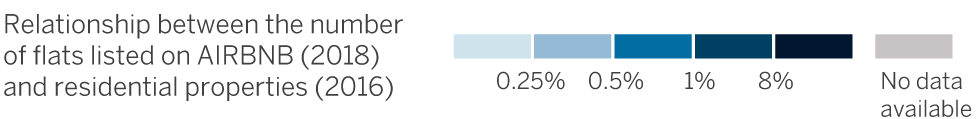

Around one in five homes in Madrid’s tourist Sol neighborhood are listed on Airbnb, according to research from EL PAÍS using data from the platform Inside Airbnb, Madrid Town Hall and registry office. Across the center, the figure is close to one in 10 homes. These figures indicate the scale of a phenomena that is rapidly changing the heart of Madrid, as it has already done to other cities. But the problem is not only having an effect on locals in the city center. Those who have decided to leave the center – either because of the prices or because the neighborhoods have become hostile – are moving to areas outside the center, which has pushed up the rent in these suburbs and accelerated the spectacular spike in the rental market, due, among other factors to the lack of offer and economic recovery.

In neighborhoods like Tetuán, Retiro, Salamanca, Chamartín, Chamberí, Arganzuela, Moncloa, Fuencarral and Barajas, the cost of rent is at its highest point since before the crisis.

In the center, rent has soared 38% since 2014. This statistic recorded last December is little consolation to Manuel, who was not able to afford a 72% rise on the rent of his three-bedroom apartment in Malasaña where he has lived for four years – €990 to €1,550. “The worst is that I have been comparing prices and it turns out that they are even asking for more for a flat like mine,” says Manuel, who asked not to give his real name because his landlord has given him extra time to find a new place and he doesn’t want to upset them.

Like Manuel, many renters in Madrid have finished or are about to renegotiate their rental contracts. In these months, the last contracts under the old Urban Rental Law will expire and the first contracts will be signed under the new law, passed in 2015. The increase in rental price which has happened over the years will take effect in one foul swoop, reducing the number of traditional rental properties even more, as landlords opt for short-term leases to tourists which are easier-to-rent and more lucrative. Between 2016 and 2017, the number of available rental properties in the Madrid region dropped by 7.3%, according to property website Servihabitat, which highlighted that the increase in prices “is very influenced by tourism rentals.”

In other words, there are lots of people looking and little on offer. “You don’t even get to see the flats. In between calling and going to see it, it’s been taken. I have seen people who have rented a place over the phone, without even going to see it. And then the landlords place increasing demands [payroll, months of bond, insurance],” says Álvaro Sánchez, a 29-year-old freelance architect, who did no expect the soaring cost of rent would be exacerbated by the anxiety and stress of looking for a place. Finally, he and his partner have decided to leave their 45 square-meter home in Lavapiés where he paid €1,000 and move across the Manzanares River to Urgel in Carabanchel.

But financial difficulties are not the only reasons why people are choosing to leave the center. With a heavy heart Sofía Velasco decided to move from the neighborhood where she grew up in because it had become unlivable for her family. She has lived in Ópera as it has undergone many changes – first gentrification, a process which made everything more expensive and little by little pushed out the locals and traditional business for more modern and expensive alternatives, and then the tourism boom, with Airbnb and rise of similar platforms in 2014. Now, surrounded by hostels, flats for tourists and students, she is following the path of many others – “in my son’s class, four are leaving this year” – and moving to a chalet outside of Madrid. “It makes me very sad but it is also a good business decision,” she explains, referring to the sale of her house.

There are locals who are resisting like the artist and teacher Eve Bauder who refused, despite all the issues – noise, dirty streets, seeing her friends leave and the conversion of her neighborhood into a “theme park for tourists” – to give up the dream which cost her so much to achieve: “I sacrificed 20 years dedicating myself to strictly saving (water and bread) and had up to three jobs and a mortgage at the same time,” she says from her home, between the Jacinto Benavente and Tirso de Molina squares. But it is true, she confesses, that everything seems to be pushing her to leave.

The cost of buying a home is also going up in the center and surrounding suburbs thanks to investors, many international, who are looking to profit from the current low interest rates. To make returns all that is needed is a call to one of the many businesses that manage tourist rental properties returns.

Like Minty Host, which was created in 2015 by four partners (and initially the only employees) which now has 20 workers and manages 140 flats in Madrid and another 30 in Sevilla. “An activity which is generating work is being demonized,” complains Guillermo Martínez, one of the partners. Asked about the problems the tourism rental market could cause, like displacing locals, the 32-year-old says “the city has always been dynamic.” He defends the benefits the business brings to suburbs like Lavapiés and the tourism industry. “It opens the possibility of people traveling who would not be able to do so in another way,” says Martínez. He believes that after its initial explosion the market will be regulated. “Many who are trying it now and not doing well,” he says.

“The problem of the property bubble is that you never exactly know when it is going to burst,” says urban planner Álavro Ardura. “The capacity to host tourist has grown enormously in very little time without having any prepared infrastructure.” For Adura the problem is market “saturation.”

What with the region of Madrid flooded with record-high number of tourists in 2017, with nearly 12 million people spending 15.9% more than in 2016, and Airport manager Aena negotiating to increase flights to Barajas international airport by 10%, many don’t believe the market will regulate itself. But Locals are asking for it. The recently created association in Lavapiés called Dónde vas? (Where are you going?) has called for a moratorium to “think about what kind of tourism we want and to stop the most pressing consequences of tourism industry: rising cost of homes, transformation of the city model, expulsion of locals.” And so are hotels, which argue the flats represent unfair competition. Even property administrators agree, arguing they should be paid more if they have to clean up, make repairs or paint more often because of the tourists.

Almost all of them believe the regulation that the region of Madrid is preparing is not enough. Under the proposed rules, neighborhood communities would be allowed to ban buildings from being used for tourism purposes in their statute. These flats would also need to obtain a suitability certificate, civil responsibility insurance and meet a number of minimum requisites like ensuring heating and fire extinguishers on the property. Failure to comply would be met with a fine of up to €300,000.

Madrid Town Hall meanwhile, wants to limit the number of days a flat can be rented to tourists (between 60 and 90 days, the exact number is yet to be decided) but it would not force property owners to obtain an urban license as a third-party establishment.

“You can’t ask a residential home to be listed as a third party, it is a regulation that is impossible to comply with and a blanket ban that we totally reject,” says David Tornos from the Association of Tourist Accommodation Managers in the region of the Madrid and the Spanish Federation of the Association of Tourism Homes and Apartments (Fevitur). He says that the regulation would be a blow to all professionals in tourism accommodation (the vast majority of whom appear in Airbnb), arguing that renting a flat for less than 90 days is longer profitable. “We are in favor of regulation. And that those who don’t meet the requirements are sanctioned and closed. But not of prohibition,” he adds.

If regulation moves in this direction, sociologist Javier Gil believes more homes will be available for long-term rental but that there will still be people renting their homes on Airbnb to complement their income. “That would be good, but it will come late,” he says.

While Tornos from Fevitur argues tourist accommodation is only pushing up the cost of rent in the center of Madrid, other reports show that it is the main factor for the entire rental market. “The growing profitability of tourist accommodation rented across platforms like Aribnb is causing a noticeable rise in the cost of long-term rental contracts,” concluded a report from the Spanish bank Bankinter.

The number of locals pushed out from their neighborhoods is not likely to be included in the census statistics but it could lead to profound consequences, not only social problems (widening the gap between rich and poor communities) but also in terms of transport (getting to work in the center, where to go for entertainment), infrastructure (if local schools are left without students, they will have to created in new areas), and in the very shape of the city. In the city of Madrid, figures from last January show that there are 18,435 food and drink establishments – a 28% rise on 2013 data and the highest number in at least the last two decades.

English version by Melissa Kitson.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.