Snow blind: how half a ton of cocaine destroyed a tiny Portuguese island

A yacht stacked with the drug set its cargo adrift with devastating effects on the local community in the Azores

Rabo de Peixe is the kind of place where you need a lot of ambition and a ton of luck to survive. Life here on the north coast of São Miguel in Portugal’s Azores archipelago is as wild, forgotten and cruel as its location in the middle of the Atlantic. Home to 7,500, the town has few facilities, save Wi-Fi. When there’s no fishing to be done, youngsters smoke hash, hang out on the cement pier and ponder how to get away from this scrap of land in the middle of nowhere where next to nothing happens.

Women were said to be using cocaine to coat their mackerel instead of flour

This goes some way to explaining how the town was brought to its knees when in June 2001, something actually did happen – in the shape of a Sun Kiss 47 yacht, carrying on board 505.840 kg of 80% pure cocaine, valued at €40 million.

The sea was rough and the gale force wind brought down the yacht’s mast. It was impossible for it to slip by the Azores Islands as planned, but it was equally impossible to come into the port, laden as it was with drugs. The crew held a crisis meeting and decided to drop some of the bales of cocaine into the sea. The rest would be taken to a cave in the north of the island, close to Rabo de Peixe.

This plan might have worked, but nature is unpredictable. What ensued was something like an Irvine Welsh version of the rubber duck incident, when 28,000 of the toys were tipped into the Pacific in 1992 to be washed ashore in Alaska and Canada 15 years later.

At the mercy of the vicious wind, the bales, like the ducks, were also blown ashore, though in a far shorter space of time. As they bobbed ever closer to the pier in Rabo de Peixe, news of their arrival tore through the town, prompting a frenzied treasure hunt. According to witnesses, dozens of people, from teenagers to grannies, ventured out onto the treacherous quay that night to fish for the goods.

The police managed to confiscate 400kg of the powder in the first-ever operation of its kind on the archipelago. The remainder was commandeered by locals, many of whom were both poor and uneducated. “The police maintained that the yacht was carrying only 500kg but that’s absurd,” says Nuno Mendes, a journalist sent from Lisbon to cover the story for the newspaper Publico. “The boat could carry up to 3,000kg and nobody is going to cross the Atlantic carrying only a small percentage of what they can take. A hundred kilos of cocaine, however exquisitely high-grade, doesn’t destroy a generation.”

According to Mendes, “Cocaine had only been used recreationally up to that point and was only affordable to youngsters from middle and upper class families. It was an occasional luxury. Problems arose when its use became more democratic and a poverty-stricken population began to consume it at will and trade with it in the most bizarre ways.”

Picture this: a typical small beer glass filled with cocaine and sold on the streets for 20,000 escudos – just over €20. No one knew the going price, nor the risks involved in consuming such high-grade powder. Neither were these concerns uppermost in their minds. The main object was to make money as fast as possible. Consequently, an epidemic of overdoses brought the hospitals on the island to the verge of collapse, prompting the health authorities to broadcast public health warnings.

“For 10 days, the warnings occupied much of the news,” says journalist Teresa Nobrega, who worked for the RTP Azores TV channel. “Doctors were coming on TV begging people to put an end to the madness. There were weeks of panic, terror and mayhem. No one was prepared for anything like it. To the point that, almost 20 years later, it continues to affect us.”

Sometimes fact and fiction can become confused but the collective memory of Rabo de Peixe recalls women using cocaine to coat their mackerel instead of flour and middle-aged men spooning it into their morning coffee. As Mark Twain would say, humor is tragedy plus time. In the case of Rabo de Peixe, perhaps not enough time has passed, though some stories would be hilarious, if they weren’t so sad.

“We never had access to reliable statistics,” says Mendes, who believes that there was a cover-up to avoid it becoming national or international news. “At first, the priority was to stop the madness, but there was a lack of resources and a lack of interest from the start. We had 20 deaths and an untold number of overdoses in the three weeks following the landing. But these are unofficial statistics that we cobbled together with the help of doctors and health workers.”

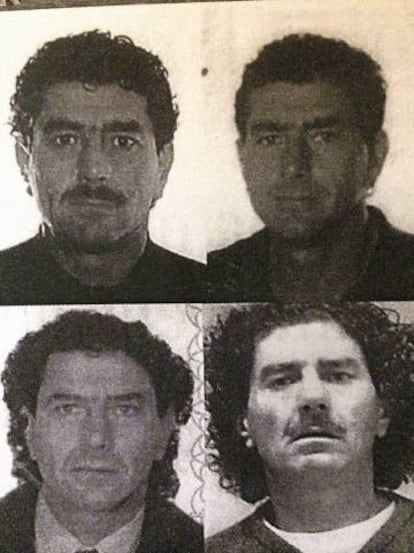

The police were working on two fronts simultaneously: confiscating every last gram of cocaine on the island that had not yet been consumed and locating the yacht that had brought the drugs in the first place. After two weeks of exhaustive searches at the port of Ponta Delgada – the island’s capital – the police found a small packet cleverly concealed in a yacht moored in the port. The packet was wrapped in newspaper bearing the same name and date as the newspaper in the bales of cocaine seized days earlier on the beach. The police arrested the only man on the boat, Antoni Quinzi, an imposing-looking Sicilian from Trapani who came without a struggle.

His arrest was key to the investigation and finding the remaining cocaine. “When we explained to him how the island had been turned into a minefield, he collaborated, giving us key information on the goods that were hidden in the north of the island,” says João Soares, who was the chief police inspector at the time. It was Soares who arrested Quinzi and who organized the hunt for him two weeks later following one of the most surreal jailbreaks in Portuguese police history.

Ten days after his arrest, Quinzi jumped over the wall of the prison, waved goodbye to the police and hightailed his way to freedom on a waiting Vespa. In a bid to offer an explanation, Soares says, “The island itself is a prison. No one escapes from jail on an island.” Well, Quinzi did, though he was apprehended again two weeks later in a barn in the north east of Sao Miguel, carrying 30 grams of cocaine and a fake passport. From there he was taken to Coimbra prison in Portugal. He was later sentenced to nine years and 10 months, after it was proven that his mission had been to direct the boat from Venezuela to the Balearic Islands. He was the only person ever held to account.

“He was very charismatic,” says Catia Beneditti, a lecturer in Italian at the Azores University who acted as Quinzi’s interpreter during his interrogation and subsequent trial in Ponta Delgada. “He was very tall, with impressive hands and a sad expression. It sounds like Stockholm Syndrome but I felt sorry for him. He gave the impression that he felt terribly guilty and didn’t know how to help.”

To this day, Quinzi is a legend on the island. Everyone knows him, despite not having seen him. Currently, the purity of cocaine is measured according to the criteria of “el Italiano”, indicating that, 17 years on, the island is still living with the fallout of that fateful night.

We had 20 deaths and an untold number of overdoses in the three weeks following the landing. But these are unofficial statistics that we cobbled together with the help of doctors and health workers

Journalist Nuno Mendes

A mobile service makes its way weekly across Sao Miguel, distributing methadone to heroin addicts. Far from being a different issue, this is in fact one of the consequences of the cocaine landing. “The purity of the cocaine had a catastrophic effect. The rush from the drug was so brutal that people started to use heroin to get to sleep,” says Suzete Frías, former director of the health clinic in Ponta Delgada. Drug addiction started to become a huge problem. “While the children from well-to-do families were sent to rehab clinics on the continent, working class children sought heroin.”

In spite of all this, the matter has never attracted much interest, remaining to this day the elephant in the room. Around 1,400 km west of Lisbon, the Azores Islands are out of earshot, no matter how hard this elephant tries to make itself heard. According to Suzete, if the cocaine had been washed up on the shores of mainland Europe, “none of this would have happened.”

Rebeca Queimaliños (Pontevedra, 1982) and Macarena Lozano (Granada, 1982), are currently making a documentary on the Azores cocaine saga.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.