The women tackling the macho world of flamenco guitar

There are no female figures of note in this male-dominated scene, but both foreign and Spanish players are starting to break down the stereotypes and inspire the next generation of girls to enter this hallowed domain. Even virtuosos, such as Tomatito, are eager to see the gender gap close

The venue is nothing special but the flamenco dancer brings it to life in a kaleidoscope of color as she spins in ecstasy on her hard flamenco heels. A whirl of fishnet stockings and blue and green frills, she is the epitome of femininity. Her hair is up, her lips are red and her eyes flash darkly behind lashings of mascara.

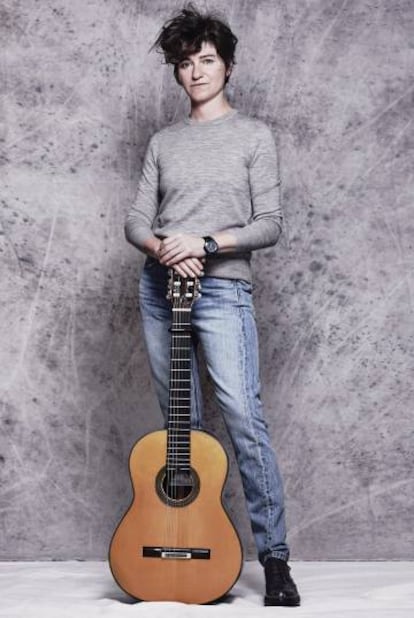

Behind her, there are four men dressed in black and a woman stripped of adornment as though she were one of the boys. Also wearing a black shirt, black trousers and low-heeled shoes, her hair is short and her face is make-up free.

This androgynous-looking woman sits with her legs crossed at a right angle. Her name is Antonia Jiménez and in her elegant arms is a flamenco guitar. The audience at the Corral de la Morería in Madrid are mostly foreign and are not offended by the sight of a female flamenco guitarist. They are not familiar with the idea the instrument should only be played by a man. But Jiménez is. She has been hearing this said practically every day since she was a child. Now aged 45, she plays flamenco internationally and is one of the best-known female guitarists on the circuit. But still the attitude persists.

“There are still no big female icons,” she says. “There are no women up there on a par with Vicente Amigo, for example. We keep struggling to pave the way.” Bit by bit, without too much noise, they are blazing the trail. There aren’t many of them and carving out their careers has been a lonely business. But finally, they are becoming more visible – a handful of role models for the next generation.

Perhaps the grueling journey toward recognition accounts for the weariness in Jiménez’s blue eyes. When she was just 27, she was ready to throw in the towel, all but defeated by the doors slamming in her face. But an advert looking for a flamenco guitarist for a Japanese tour came to the rescue. She was the only female candidate to apply but she nailed the job. “They held auditions in Barcelona, Madrid and Seville,” she says. “And in Seville alone there were more than 100 hopefuls, so you can imagine. I spent a year in Japan. And it changed my life. You get up on stage three times a day there and you make money. When I came back to Spain, I was in the same predicament, but I was stronger. I could wait because I had savings, experience and an underlying confidence. I started to play for prestigious dancers.”

In the music conservatories across the Andaluz region, only one in 10 flamenco guitar students are female

Jiménez makes much of the dancers she has played for because the traditional role of the flamenco guitarist is one of accompaniment, either to a song or a dance. And if a singer or dancer refuses to have a woman accompanying their art – something that happens a lot – it can be a game-changer.

Opportunities are thin on the ground for female flamenco guitarists. Hence the lack of female students and female teachers. In Andalusia, the cradle of flamenco, only six out of 68 flamenco teachers in the music conservatories are women. In other words, one in 10. Among them is Laura González, who teaches in the Professional Music Conservatory in Jaen. She is not surprised by the gender disparity among the teachers. There were scarcely any girls studying flamenco guitar when she was young. And although she sees the balance being redressed, there is still only one female student in her conservatory and almost 20 boys.

González wears her blond hair loose over her shoulders. She also wears black eyeliner and pink lipstick. She was not able to perform like Jiménez. It was simply never on the cards. “I ended up teaching but there was a time when I would have liked to have played gigs and accompanied singers and dancers. Now, I’m not sure because I have a son and a family and I like teaching. I’m not teaching because I couldn’t perform. It’s a vocation, but it’s true that a few years ago I would have gone wherever I was asked. I was really keen.”

So what was the problem? A lack of opportunity? Yes, she says dryly.

Female flamenco guitarists are so rare that Eulalia Pablo, a retired flamenco teacher and lecturer at the University of Seville, is often asked by her students why and if it was always like this. Analyzing press clippings from the 18th and 19th century, Pablo tries to answer these questions in her book Mujeres Guitarristas – Female Guitarists. “It’s a myth that women have never played the guitar,” she says. “But the flamenco world has always been very macho and inflexible. It remained that way until last century.”

Of course, it wasn’t just careers in flamenco guitar that women had to fight for – they struggled to be taken seriously in any area. And while playing an instrument formed part of a young lady’s education, their ability was seen as purely decorative – a means of entertaining the men. That, according to Pablo, is why upper-class women were such proficient piano players. “Of course, playing outside the home was forbidden to them. Very few became professional and, if they did, their careers were short. As soon as they were married, they were expected to stay at home.”

In the future, there will be no gender issue when it comes to the guitar. It’s such nonsense, just cliché. Either you play well or you’re out Flamenco virtuoso Tomatito

In the 19th century, the situation changed when singers became popular in cafés during what is known as the café cantante period. “The audience was male because women didn’t go out at night and the men wanted to see women,” says Pablo. “They liked the singer to be beautiful and the dancer to have a good body. In these bars, the director of the ensemble was the guitarist. He decided who would be taken on. So naturally, in that era, what guy was going to put up with a woman giving him orders?”

In spite of everything, there was one woman who managed to leave her mark. Her name was Adela Cubas, an exceptional guitarist who tended to describe herself as “ugly”. In her book, Pablo writes that Cubas broke the record in the 20th century for media attention concerning the career path and technique of a female flamenco guitarist.

Pablo includes an interview with Cubas in the book, introducing her as the best female flamenco guitarist of the era. “I am very ugly and ugly women don’t thrive in the theater, however good they are,” Cubas is quoted as saying. “No one, not journalists or sponsors will promote them. And if they are not promoted, they won’t get big, and they won’t get famous. Work alone doesn’t make people rich. All singers earn more than me, even those just beginning.”

Self-taught, Cubas had to work as a guitarist as a child to make money for her struggling family. She was extremely talented and eventually made it professionally. This is reflected in reviews of her performances, which all ended in standing ovations in Spain. However, when she tried to take her art abroad, she wasn’t so lucky. “I have been on the point of going to America twice but both times I have failed,” she said. “The first time was because the sponsor found me so horrible to look at, he said he would only take me on if I turned my back to the audience. The second time, I was pushed out by a dog… Given the choice between a wise dog and an ugly woman, the sponsor preferred the dog.”

It wasn’t easy for Cubas and the women of her generation but those coming after them had it even worse. “The Franco dictatorship meant the steps made by the women’s movement for women’s rights in the world of work, particularly in certain areas, went into reverse,” writes Pablo. Add to that the rigid attitudes toward women that flourished within flamenco culture.

When democracy eventually arrived in Spain following Franco’s death, these female guitarists resumed the struggle. But the Spanish girls who wanted to play, such as Jiménez and González, were exposed to attitudes that seriously challenged their enthusiasm: “Women can’t play the guitar because they’re not strong enough,” it was said. “If you’re a girl, you play classical guitar. Flamenco is for men.” And, “They don’t know how to drive the rhythm.” Many gave up and the task of keeping a female presence in the world of flamenco guitar fell to foreigners such as Bettina Flater, Elena San Román, Noa Drezner, Kati Golenko and Afra Rubino.

The Spanish female flamenco guitarists faced criticism from childhood. A lot gave up and it’s foreigners who have continued to battle for the female representation

Never once had these women heard that flamenco guitar was not for them on account of their sex. As adults, they came to Spain to perfect their technique, only to find the obstacles they encountered for being foreign were nothing compared to those posed by being female. The Swedish guitarist Afro Rubino recalls a party in Seville when the hostess asked each of the musicians what they did. “I replied that I played the guitar and the hostess said, ‘You play guitar? Why don’t you just cut your hair and get a penis?’ I laughed because there was no other way to react to such remarks. But the women looked at me so sternly that in the end I had to tell her that I also sang and danced. And the problem was solved. I’ve even been told that women can’t play the guitar because they ruin their nail varnish,” she says. “As I’m foreign, I don’t get so many remarks and the ones I get are more in the line of, ‘Ah, the Swede! You’ll never guess how well the Swede plays!’”

These foreign women were in an alien environment, but they were in a stronger position than their Spanish counterparts. They arrived in Spain focused on pursuing their career. By the time they heard the off-putting remarks, they were adults and they knew how to field them.

“The problem with flamenco is it’s still a very ethnic art which is starting to become more universal,” says Enrique Vargas, who teaches Jiménez and Kati Galenko, a 31-year-old American, who is also set to take the flamenco world by storm. “Camarón was even asked as a child how he expected to sing well if he was blond. Things are now much more accessible because there are a lot of foreigners who have shown that they can play well. And the most orthodox people in the flamenco world have started to admit as much. It’s the same with women. There weren’t female flamenco guitarists before and now look at my Antonia!”

Vargas arranged music for the late Paco de Lucía and he remembers the famous guitarist saying that he would have liked to have had female colleagues. “He said that about 25 years ago,” says Vargas. “I guessed that he hadn’t come across any. Paco loved women in flamenco. And I’m sure he would have been generous with his ‘Olés’ to a female flamenco guitarist. Sometimes men are too heavy handed. Women bring a more lyrical, romantic and sensitive touch. That’s ideal for flamenco. There are a lot of women in this art and it would be poorer without them. Humanity is made up of men and women; if men dominate, it means we are losing out on the other side.”

There are not many girls in Vargas’s classes. Only three or four of his 50 pupils are female, reflecting how hard it is to be taken seriously. “How many times have I heard, ‘How can a woman play well when she doesn’t have the right wrist action or strength?’ It drives me mad. It’s stupid and there’s no basis for it.”

Tomatito also finds these attitudes hard to bear. “Strength? Strength is for carrying bags of cement,” he says. “It’s for oxen. It has nothing to do with playing guitar.”

A flamenco star from Almeria, Tomatito has scarcely come across women guitarists during the course of his career. But he remembers one in his neighborhood, a foreigner they called María. “It’s very new and there are no established female flamenco guitarists. But in the future, there will be no gender issue when it comes to the guitar. Really. It’s such nonsense, just cliché. Either you play well or you’re out.”

English version by Heather Galloway.