Hugh Thomas: “Charming, generous and quite thin-skinned”

British historian Paul Preston remembers the author of the groundbreaking ‘The Spanish Civil War’

I first met Hugh Thomas in 1968 when I arrived at the University of Reading to study for a Masters’ degree in Contemporary European Studies. I had previously been at Oxford where I was deeply disappointed by the lack of opportunity to work on contemporary history. The opportunity to study with Thomas made a welcome change. At the time, of course, I knew little about him other than that he was the author of the great book on the Spanish Civil War published seven years earlier.

Born in 1931, Hugh Thomas was the only son a British colonial officer in what was then the Gold Coast, now Ghana. His uncle, Sir Shenton Thomas, was the governor of Singapore who surrendered to the Japanese invaders in 1942. Hugh studied history, not very assiduously, at Queen’s College Cambridge but did attain prominence as a swashbuckling Tory president of the Union. When he came down, he led a champagne-fueled life as a man-about-London.

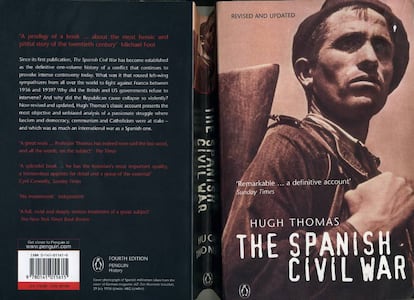

‘The Spanish Civil War’ was quickly established in the popular mind as the book on the conflict

He was locally recruited for the Paris Embassy, thanks, it was said, to the influence of Harold Nicholson, who was a friend of the then-ambassador, Sir Gladwyn Jebb. He left in early 1957, claiming that he did so because of disgust with the British role in the Suez crisis. However, he may have jumped before he was pushed. Rumors swirled around about important documents inadvertently left on the Metro and/or an affair with the wife of a French Minister. The publicity given to his clash with the Foreign Office made him an attractive catch for the Labour Party. He stood, unsuccessfully, as parliamentary candidate in 1957-1958 for Ruislip and Norwood. His altered allegiance was cemented when he edited an attack on the political elite in The Establishment in 1959.

However, this did not solve the issue of an income. A brief stint as a lecturer at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst did not satisfy him. He tried his hand as a novelist but The Oxygen Age (1958) did not sell. However, the previous year’s equally unsuccessful The World’s Game would change his life. Dedicated to Gladwyn Jebb’s friend Nancy Mitford, it cemented an already key connection. More importantly, it had been read by the gentleman-publisher, James McGibbon, then a literary agent with Curtis Brown. McGibbon invited him to lunch and told him that the scene in his novel where the hero went to fight in Israel had reminded him of volunteers in the Spanish Civil War. Remarking that the time was ripe for a broad survey of the war, he urged Hugh to make a pitch. It was taken up by Eyre and Spottiswood. Although he did not know any Spanish, Hugh set to reading voraciously and ruthlessly picking the brains of innumerable participants on both sides, as well as of the war correspondent Henry Buckley and the great expert on the conflict, Herbert Southworth.

Banned in General Franco’s Spain, the translation became a clandestine best-seller

Published in 1961, it was quickly established in the popular mind as the book on the Spanish war. Eulogistic reviews from liberal pundits such as Cyril Connolly and Michael Foot saw the book widely accepted as a classic and it would go on to sell nearly a million copies throughout the world. Not only was it written in a colorful and highly readable style, but The Spanish Civil War was the first attempt at an objective general view of a struggle that still excited the passions of right and left.

Although banned in General Franco’s Spain, the translation by an exiled Spanish publishing house in Paris, Ruedo Ibérico, became a clandestine best-seller. The dictator’s propagandists had never ceased proclaiming that the war had been a crusade against communist barbarism. However, the impact of foreign works by Thomas and Southworth, smuggled in despite the efforts of the frontier police, entirely discredited the standard regime line. An example of the regime’s efforts to stifle the impact of Hugh’s book was the case of Octavio Jordá, a 31-year-old working-class Valencian who was arrested at the French border with two suitcases packed with copies of The Spanish Civil War. At his subsequent trial, he was found guilty of “illegal propaganda” and “spreading communism” and sentenced to two years’ imprisonment.

In response to Thomas and Southworth, Franco’s then-minister of information, Manuel Fraga, set up an official center for Civil War studies to streamline crusade historiography. It was too late. So successful was the book that even Franco himself was regularly asked to comment on statements in the book. The Caudillo largely dismissed it all as lies, denying that civilians were killed when he bombed Barcelona or that there were mass executions. The notoriety of Thomas’s book success would underlie colossal sales after the dictator’s death in 1975. In frustration, the Center’s director, Ricardo de la Cierva, called Thomas’s book a “Vademecum for simpletons.”

Now financially more secure, in 1962, he married the beautiful Vanessa Jebb, daughter of Lord Gladwyn Jebb. A serene influence, she was the jewel of the glittering social circle that met at their home in Ladbroke Grove. She gave him three children, Inigo, Isambard and Isabella. In 1966, he was made Professor of History at the University of Reading. He was a thoroughly entertaining and popular teacher, as I saw for myself as a Masters’ student. He was never comfortable with the creeping administrative demands of academic life and I substituted for him when he took a sabbatical to concentrate on his writing.

During this time, I worked as his research assistant on the third edition of The Spanish Civil War. He resigned in 1976. My good fortune in working with him meant that I was often invited to his home and met hugely interesting people. Thanks to that, I met and became friends with the great Cuban writer, Guillermo Cabrera Infante, and made the contact with Ramón Serrano Súñer that opened the door to my many later interviews with him while I was working on my biography of Franco. Whether in intellectual or social circles, Hugh could be charming and generous but he was quite thin-skinned. He did not take criticism lightly or, indeed, at all, as a bitter polemic with Herbert Southworth in the Times Literary Supplement demonstrated.

Even before going to Reading, he had begun research for his gigantic history, Cuba or the Pursuit of Freedom. At nearly 1,700 pages, it was not a success. Its long early survey of the Island’s history, beginning with the British occupation of Havana, was found to be hard going by many readers. Only when it reached Castro’s revolution did it match the confident sweep of the Spanish book. After Cuba, he was commissioned to do a similar job on Venezuela but never really got started. Moreover, he felt constrained after spending, as he put it, “seven years in the study of a short period in the history of a small society and it is, therefore, natural that I should wish to write on a more generous scale.” The result was An Unfinished History of the World, published in 1979.

In the 1980s, Thomas became an advisor to Mrs Thatcher

At the behest of his friend Roy Jenkins, he had another unsuccessful attempt to secure a Labour seat but was thwarted by members of the Trotskyist Militant Tendency on the selection committee. Thereafter, if not in consequence, he publicly declared his abandonment of the Labour Party and his embrace of Thatcherite free-market economics. He became one of her unofficial advisers and was made chairman of her think-tank, the Centre for Policy Studies in succession to Keith Joseph. In line with his new political vocation, when An Unfinished History of the World was awarded a £7,500 Arts Council Literary Award in April 1980, he refused to take the check. Saying that his bank manager would be aghast, he made the gesture on the grounds that the final chapters of the book argued that “the intervention of the state (leads) to the decay of civilization and the collapse of societies.” In History, Capitalism and Freedom, a pamphlet published with a foreword by Mrs. Thatcher, he argued that the decline of Britain was the consequence of the encroachment of the state. At the Centre for Policy Studies, he tried to help Keith Joseph, now Minister of Education, to re-establish a sense of the glories of English history which they both believed had been obscured by the works of Eric Hobsbawm, E.P. Thompson and others. It was a project that belied his own works on Spain and Cuba and led to accusations that a first-class historian was trying to turn a subject on which he had never worked into “hollow, pseudo-patriotic indoctrination.”

In his 1983 pamphlet, Our Place in the World, he attributed the decline of Britain to the transformation of “the old England of individualism and laissez-faire into an England organized from above.” He was rewarded by being ennobled as Lord Thomas of Swynnerton and there were rumors that he might be sent to Madrid as ambassador, although the deficiencies of his Spanish might have rendered the job difficult.

Thomas spent the last 20 years of his life working on a series of books about imperial Spain

After the defeat of Mrs. Thatcher in 1990, his prominence in the Tory Party diminished and he was increasingly disillusioned by what he saw as a festering Euro-skepticism. Finally, in November 1997, he crossed the floor of the House of Lords to the Liberal-Democrat benches. He announced: “I have resigned the Conservative whip in the House of Lords because since the election of May 1st last, its attitudes towards the European Union as it is presently constituted, and as it is likely to develop, have become ever more critical and skeptical.”

Finally free of the politics that had never really fulfilled him; he returned to his real métier and began to write a series of flamboyant works on imperial Spain. The sparkling narrative drive of his work on Spain was carried over first into The Conquest of Mexico (1993) and then The History of the Atlantic Slave Trade 1440–1870 (1997). They were followed by what was his crowning achievement, a trilogy about the Spanish Empire, consisting of Rivers of Gold (2003); The Golden Age: The Spanish Empire of Charles V (2010) and World Without End: The Global Empire of Philip II (2014). When I last spoke to him a couple of weeks before his death, he was fulminating about Brexit.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.