How millions of fans are watching pirated soccer on Facebook Live

Network of pages and specialist sites are attracting countless viewers in Spanish-speaking world

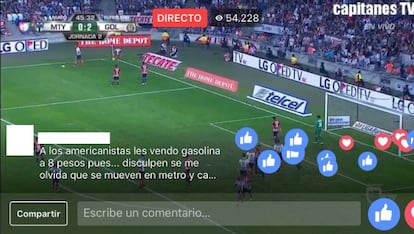

Dozens of Spanish and Latin American Facebook pages are illegally broadcasting top-flight soccer matches free of charge using the social network’s video-sharing facility on Facebook Live. Through a combination of links and profiles that disappear as soon as the match is finished, these pirate broadcasts are seen by hundreds of thousands of fans.

On December 3, Barcelona hosted Real Madrid at the Camp Nou stadium, traditionally one of the biggest matches of the year in Spain, and watched by fans around the globe. For the first time, the game was being broadcast in the ultra-high definition 4K format using super zoom, 360-degree cameras, and was watched by more than 600 million people in 185 countries. beIN Sports, a spin-off of the Al Jazeera network, retransmitted the game in Spain, estimating an audience of 2.2 million. But the transmission was pirated via Facebook Live, reaching many more on sites such as Capitanes del Fútbol, which at one point was being watched by 700,000 people simultaneously, and which had, by half time, clocked up 4.6 million views.

As long as people are not making money from retransmitting matches, the practice is not illegal

Sites like Capitanes del Fútbol, Planeta Fútbol and Fútbol Directo Honduras, among many others, get around Facebook’s rules by advertising pages that transmit games illegally and then providing links to them.

These sites create a network of intermediary profiles that redirect to other sites that have tapped into the broadcast and are illegally transmitting it. Once the game is over, the network of pages closes down; sometimes it is created for a single match. The sites then return to being seemingly innocuous pages dedicated to soccer news and gossip.

These sites are directed mainly at a Spanish-speaking public, particularly in Latin America. Most of the time they tap into beIN Sports Ñ channel, which can be subscribed to in the United States. Although it cannot be proved that they are part of the same network, the main pirate sites and the temporary pages have similar names: Capis TV, Capitanes TV2, El tío Capi, Rincón Futbolero, etc. The Verne department of EL PAÍS received no reply when it contacted them.

A spokesman for Spain’s La Liga soccer league explained that it is very hard to shut these sites down because of the flexibility that Facebook Live offers.

“We have agreements with the social networks to look for illegal content,” says La Liga. “In the case of Twitter, they are removed as soon as we detect them. Facebook has its own tools, which makes it quicker to remove these videos. But all that happens is that one page closes and another opens immediately.”

Facebook launched its video-streaming service in late 2015. Over the course of 2016 it has boosted its Live content, giving it priority over articles in the algorithm that decides what to show users.

Technically, any smartphone connected to the internet can broadcast a video live. Broadcasting a soccer match by tapping into a feed is not difficult. All that is required is a pay-to-view subscription to a match and video retransmission software, which can be downloaded free. The stream is then synchronized with Facebook through a password on the social network, creating a broadcast-quality live stream.

Facebook Live has been used by people via their smartphones to capture a number of controversial incidents over the last year, among them the killing of an unarmed black man by police in the United States.

Facebook Live makes it easier than ever to view pirated content, ending the search for sites and then trying links where sound and image are often out of sync. In essence, somebody who forms part of a chain is simply a member of a community of soccer fans. Sometimes people do not even watch matches: if one of your contacts clicks on Like or shares the game, it can appear on your Facebook page without you even looking for it.

David Maeztu of Spanish law firm Abanlex and who specializes in internet and intellectual copyright, says that the law does not interpret the actions of people who watch this kind of content as illegal, “because this behavior does not indicate a desire to make money, as required by article 270 [of the Penal Code, relating to intellectual property]. The same applies to people who tap into a signal, as long as they are not making money from it, he adds.

English version by Nick Lyne.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.