How a Ukrainian soccer player became a political football in Spain

Fans pressure Madrid’s Rayo Vallecano to expel Roman Zozulya over alleged neo-Nazi links

There are no security guards outside the training ground of Spanish second-division soccer club Rayo Vallecano in Madrid. Neighbors, curious onlookers, fans, players and club officials all mill around together from early in the morning on. The daily menu at the club restaurant costs €8.50 (around $9) and the view through the windows shows fans in the rain hoping to catch a glimpse of the players.

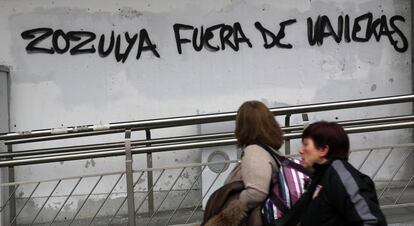

On Wednesday, a small group of supporters of the club, which is based just a few kilometers away from glamorous Real Madrid, took to the stands to protest the arrival on loan of Ukrainian player Roman Zozulya, a 28-year-old forward, over alleged neo-Nazi links.

Here we play soccer, independent of ideology, religious and sexual orientation or skin color Raúl Martín Presa, Rayo Vallecano owner

Zozulya, who has strongly denied the connection, lasted just one training session with the Madrid team before the pressure became too great and it was announced he would return to Seville’s Real Betis club.

On Thursday, Rayo Vallecano staff were in agreement that they had made a mistake in signing the player whose demonstrated militant nationalism – in the best of cases – clashed with the values of the community represented by the club.

“This neighborhood is working-class, like our fans,” they said of the club, which is famous in Spain for its singular class consciousness.

Rayo Vallecano is privately owned with 98.6% of all shares in the hands of businessman Raúl Martín Presa. But the feeling that the club is a public asset is widespread at the club’s training grounds, which are on land ceded by Madrid’s regional government in 2006.

“Today soccer clubs don’t communicate, they keep silent,” says Carlos Navarro Montoya, former goalkeeper with legendary Argentinean club Boca Juniors and one of a group of parents waiting for their children to participate in a training session with the club’s junior squad.

“Clubs nowadays direct their communications activities over great distances, they are thinking about China. But players need something else. They need what Rayo gives them: contact with reality, and closeness to the people. [Clubs] shouldn’t forget that life as a soccer player begins and ends with everyday people on the street.”

Javier Ferrero, president of the Planeta Rayista (Planet Rayo) fan club and vice-president of the ADRV, an association the represents most of the club’s fan groups, says what many others have been saying: “I have been a member of Rayo since I was born but I would prefer to go down to a lower division than see Zozulaya wearing our jersey.”

ADRV president Ángel Domínguez echoes these sentiments. “You can read all about people on the internet. When I found out about the signing [of the player], I warned the club it didn’t fit with our values, which are solidarity and assistance for the most disadvantaged groups. Bringing in a player who boasted about belonging to a Nazi group in Ukraine goes against our principles," he says.

“He [Zozulaya] has proved it himself by posting photos of Stepán Bandera, the best-known Nazi collaborator in Ukraine during the World War II, and by taking photos of himself with the Azov Regiment,” adds Domínguez, referring to Ukraine’s National Guard, some of whose members have been accused of having neo-Nazi sympathies.

Zozulya says he is the victim of a misunderstanding after a Ukraine badge on his shirt was wrongly identified

Domínguez argues the protests against the Ukrainian player were not the work of the well-known hardcore Bukaneros fan collective – the best known of the club’s radical fan groups and organizers of social initiatives such as anti-racism days or a rainbow shirt campaign against homophobia.

“This is not an initiative of the ultras,” he explains, employing the word used to describe hardcore soccer fans in Spain. “We informed the club via various different fan groups. But the decision of the president [to sign the player] is in line with his other decisions. Presa swims against the tide.”

According to Domínguez, various club executives said they would look into the Zozulaya issue but Presa unilaterally signed the player.

For his part, the club’s owner is keen on having the signing reviewed again.

“I don’t talk about politics because I don’t know anything about it, but the main values of Rayo are tolerance and respect,” says Presa.

“Here we play soccer, independent of ideology, religious and sexual orientation or skin color. This is a club full of good people who are involved in social causes. What happened on Wednesday [with the protest] was the fault of just a few individuals who don’t represent Rayo,” he says, adding the team's sporting directors watch football and are "not historians, philosophers or sociologists".

Bringing in a player who boasted about belonging to a Nazi group in Ukraine is against our principles Ángel Domíngez, fan group association president

Presa is continuing to push for the signing of the controversial player but most fans are still against his presence. One has sent a video through to the club which apparently shows Zozulya, in plain clothes, rushing onto a soccer pitch in the Ukraine to attack an umpire.

But Zozulya has defended himself. In a letter to the club’s fans published this week, he explained he had been the victim of a misunderstanding on arriving in Spain with a journalist mistaking the Ukraine badge on his shirt for the symbol of a paramilitary group.

The article was subsequently pulled by the paper in question, Zozulya said, adding he had helped the Ukraine army to defend his country and had aided children and the disadvantaged “during a tremendously difficult time of war in Ukraine.”

English version by George Mills.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.