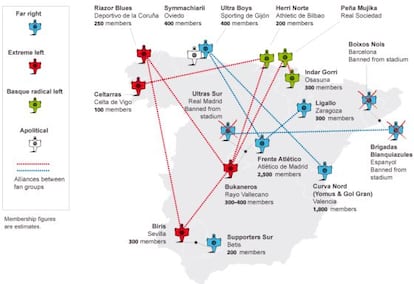

Spain’s soccer hooligan map

The recent death of a Deportivo fan in a fight in Madrid shows violence is still a problem

The 1990s was a golden age for Spain’s ultras, or soccer hooligans, a time when some clubs even courted hardcore fans, allowing groups of extreme rightwing or leftwing supporters to practically do as they pleased in their stadiums. Either way, games would often end with violent confrontations between home and away fans. Clubs only began to take action when heavy fines started to be imposed and stadiums closed. Over the last decade, as sides began to distance themselves from hooligans, or directly ban certain groups, most stadiums have returned to normality. Which is why last week’s fight outside Atlético Madrid’s stadium between home fans and those of visiting Deportivo de la Coruña – which resulted in one death and several serious injuries – caught the authorities off guard, signaling that violence remains a problem within some of Spain’s leading soccer clubs.

GALICIA

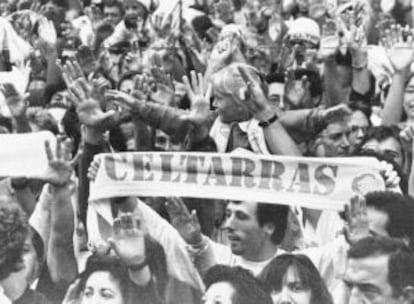

Celtarras and Riazor Blues

At second division Celta Vigo’s game against Eibar the day before the fight between Atlético Madrid fans and Deportivo supporters, whistling and jeering from the home fans’ end, which is occupied by the so-called Celtarras, interrupted a minute’s silence in honor of a female police officer shot and killed the week before during a bungled bank robbery in Vigo. The referee called off the minute’s silence and began the match. Celta later issued a statement blaming the incident on what it called a “small number of fans.”

Since Mexican businessman Carlos Mouriño took over as president in 2006, Celta no longer provides any support to its hardcore supporters, who have traditionally identified with the extreme left. But in 2013, following pressure from the fan base, the club decided against hiring Salva Ballesta, now coach at Málaga, who is known for his outspoken, right-wing political views, and once suggested sending the armed forces into the Basque Country to deal with ETA.

Also nominally on the far-left, the Riazor Blues take their name from Deportivo’s Riazor stadium, appearing in the mid-1980s in response to violent incidents in matches against regional rivals Celta. Their position was strengthened by the public support they were given by Deportivo players such as Arsenio and Bebeto, and at one point they even had their own offices in Deportivo’s stadium. In 2003, one of the group’s members was killed in a fight after a match in Santiago de Compostela, after which it announced it was disbanding. But over the last few years, it has made something of a comeback, fighting fans in Zaragoza and Gijón. At the same time, it has links to left-wing fan groups at Rayo Vallecano and Sevilla. The police estimate that the group numbers around 250.

ASTURIAS

Regional rivals

Since they first appeared in 1981, the so-called Ultra Boys of Sporting Gijón have been involved in any number of violent incidents, particularly during away matches. Sources at the club put membership of the neo-fascist group at around 400, although only a few dozen are considered dangerous by police. Their relationship with the club has had its ups and downs over the last three decades, although the Ultra Boys have storage space for their banners at the El Molinón ground. In 2005, they organized a fundraiser on the occasion of the side’s centenary.

The hardcore fans of Asturias’ other main club, Real Oviedo, are known as the Symmachiarii, after a local tribe during the Roman era. Sworn enemies of the Ultra Boys, they are resolutely non-political, and do not allow any banners or flags in support of either the right or left during matches. In 2003, the side was demoted from the second to the fourth tier of Spanish soccer for financial mismanagement.

THE BASQUE COUNTRY AND NAVARRE

Pro-independence fan base

Athletic Bilbao’s hardcore supporters club is known as Herri Norte (the Northerners), and was set up in the early 1980s. It currently has around 200 members, who call themselves antifascist and anti-racist, and also support independence for the Basque Country. Over the years Herri Norte has undergone many changes of leadership, and is now in the midst of a struggle for control over the space it is allocated in the club’s stadium. It regularly engages in pitched battles with visiting fans, most recently those of Portuguese side Porto.

Also pro-independence and nominally anti-fascist, Real Sociedad’s Peña Mujika was set up around the same time, after the San Sebastián-based side won the Spanish league two seasons in a row. It had more or less died out toward the end of the 1980s, but resurfaced in 1989. Its name comes from that of a factory close to the side’s former Atotxa stadium.

The Indar Gorri, or Red Force, supports Osasuna, Pamplona’s soccer team, and like its rivals in Bilbao and San Sebastián is an anti-fascist group that supports independence. It considers Navarre to be part of the Basque homeland, and fills the home end of the Sadar stadium with green, white and red ikurriña Basque flags. The group regularly engages in running fights with visiting Real Madrid and Zaragoza supporters.

VALENCIA

Far right

The Curva Nord (North End) is made up of around 1,800 fans, around 100 of whom the police consider dangerous. Last season, around 70 were involved in a brawl with Atlético Madrid fans in a bar in the Spanish capital. In December 2012, one of its members threw a firework into the VIP area occupied by members of Real Sociedad’s management. The Curva Nord was created in 2009 out of different Valencia supporters’ associations in a bid to control the Yomus far-right group. Recent seasons have seen repeated incidents at the Mestalla stadium. Valencia’s other main sides, Elche and Levante, have also attracted far-right groups.

ANDALUSIA

Sevilla-Betis rivalry

Los Biris is Spain’s oldest hardcore fan group, set up in 1975, and named in honor of Biri Biri, a Gambian striker who played for Sevilla between 1973 and 1978. Left-leaning, it is well organized and funded. Recent years have seen it launch campaigns in support of the removal of former club president José María del Nido, who was jailed in December 2013 for corruption. The group now has good relations with the new management, and was given a large number of tickets to the Europa League final in Turin earlier this year, which Sevilla won on penalties. Its arch-rival is Atlético Madrid, but it has good relations with other left-leaning groups.

Seville’s other soccer side, Betis, once had around 1,000 hardcore far-right fans, but numbers have dwindled to around 200. They have traditionally been backed by the club’s management, who paid for away trips and provided free tickets in the hope of preventing violence at the stadium.

MADRID

A popular front

The Frente Atlético is largely responsible for the electric atmosphere at Atlético Madrid’s Vicente Calderón stadium, and have been involved in dozens of violent incidents over the years, the most recent being the fatal fight outside the ground on November 30, which may well see it lose its place in the southern end. Numbering around 2,500, only around 100 are dangerous, say police. The group emerged in the early 1980s, and has been allowed to display Nazi symbols. In 1998, a Real Sociedad fan was beaten to death outside the Calderón by members of the Frente Atlético.

Across the other side of the city, Rayo Vallecano’s left-leaning Bukaneros have been a regular presence in the working-class Vallecas district, taking part in demonstrations to protest austerity cuts, and last month even pressuring the club to come to the rescue of an 84-year-old widow whose home had been repossessed.

ZARAGOZA

Infighting

Last month, fighting broke out between rival groups of Zaragoza fans, the neo-fascist Ligallo and the far-left Avispero. The Ligallo has been involved in numerous incidents during games against Basque teams, as well as against Osasuna.

Barcelona and Real Madrid tackle their hardcore fans

Joan Laporta was the first Barcelona FC president to confront the problem of violence in and around the Camp Nou stadium, banning the so-called Boixos Nois (Crazy Boys) in 2005, prompting death threats against him. In 1991, an Espanyol fan was murdered by Boixos Nois outside the Camp Nou, while the Mossos d’Esquadra Catalan police said recently that Barcelona’s management was not cooperating sufficiently to help eradicate the group once and for all. The Mossos are this week investigating an attack that saw two Paris Saint-Germain supporters stabbed in the vicinity of the Camp Nou on Wednesday, just as Barcelona’s Champions League match against the French club was finishing at the stadium.

Last year, Real Madrid President Florentino Pérez dissolved the Ultras Sur group, which for the previous three decades had occupied the area behind the goal in the south end of the Santiago Bernabéu stadium. Members with convictions for violence were expelled from the club. Like their arch-enemies in Barcelona, the group had for many years been allowed to display Nazi flags and symbols at games, and enjoyed special privileges. But a pitch invasion at the end of a Champions League semifinal in 1998 spelled the beginning of the end.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.