Sanmao: a Chinese woman’s tragic love story in Spain

The work of a writer with millions of followers in Asia is out for the first time in the West

There is a grave at the cemetery on the Canarian island of La Palma that is always garlanded with fresh flowers.

This is the final resting place of a Spanish diver named José María Quero, who drowned off the island on September 30, 1979.

During my time in the desert, I became an uncomplicated, laid-back woman who enjoys solitude

Sanmao

The flowers on his grave are not left by his relatives, who live on the Spanish mainland. Instead, they are brought by Chinese, Taiwanese, Korean and Japanese tourists who refer to him familiarly as José.

They know him through the books written by his wife, Chinese author Sanmao. A celebrity in Asia, Sanmao, whose real name was Chen Ping, committed suicide in 1991, but her work continues to top the bestselling charts, with 10 million copies of her books sold in the last five years.

Chen Ping retains a cult following in Asia even after death, in part because her books have fueled the dreams of millions of readers with their accounts of exotic worlds, and also because of her own life, which could have been taken from a novel.

Sanmao has come to represent the epitome of the cultivated, liberated woman; someone who traveled the world in her thirst for learning, and was then prepared to settle down in the loneliness of the desert, then later in the Canary Islands, to be with the love of her life.

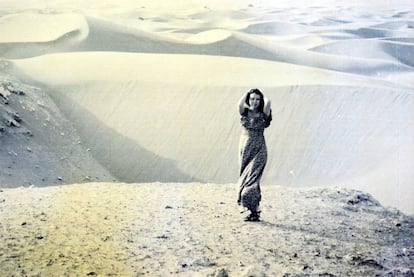

It was precisely this isolation that helped her focus on what would become her best-known work, The Story of the Sahara (available only in its original Chinese edition), a collection of essays about her life between 1974 and 1975. Many Asian readers still travel to the places she describes in her account.

“Why has nobody published this in the Western world?” wondered Iolanda Batallé when she first came across Sanmao’s work two years ago.

At the time, Batallé was setting up a new publishing house, Rata, and looking for “authors who write with their heart, their guts and out of need.”

“I found this woman who wrote about what she saw in the simplest way, without filters. It was exactly the kind of thing I was looking for,” she says.

Unable to remain in Spain without her love, Sanmao returned to Taiwan

Batallé decided to turn The Story of the Sahara into Rata’s first title, which is being released in Spanish and Catalan simultaneously. It will be the first time that Sanmao’s work is available in a Western language.

So what was a cultivated Chinese woman doing in the poverty-stricken, politically volatile Spanish Sahara of the 1970s?

Sanmao was born in mainland China in 1943, but at the age of six, fleeing the Communist Party takeover, her family moved to Taiwan.

“One day, in 1967, she showed up at our upstairs neighbor’s apartment in Madrid. He was the chef at the Taiwanese embassy in Spain at the time,” recalls Carmen Quero, one of José’s seven siblings.

“We were living in the barrio de la Concepción, a very modest neighborhood in those days. It was very unusual to see Chinese people there,” says Carmen.

“I was 19 and José was 16. She was already 24, and she had arrived from Germany after traveling in the United States and other countries. She had studied philosophy, languages, literature. We were fascinated by her. He fell in love with her at first sight,” continues José’s sister.

And so began a love story that would end in tragedy. José proposed, but she considered him too young and moved on. Sanmao returned to Taiwan, taught at a university, fell in love with a German teacher and became engaged to be married.

But the groom died shortly before the wedding. This would be the first tragedy Sanmao would have to deal with. It was also the first time she attempted suicide, cutting her wrists.

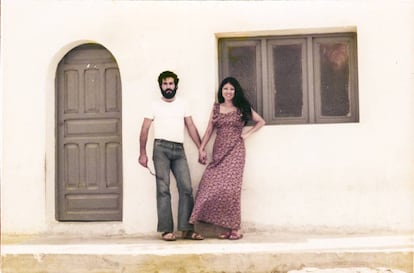

In 1973 she returned to Madrid. José had just completed his military service and had trained as a diver. He had not forgotten her. This time, she returned his advances.

Two months later, the couple met with Carmen at a cafeteria to let her know that they meant to be married. Soon after that, José was offered a job in Laayoune, in modern-day Western Sahara, which at the time was still a Spanish colony.

I found this woman who wrote about what she saw without complications, without filters

Iolanda Batallé, publisher

That is where they celebrated their wedding and lived until 1975, when Spain relinquished the territory to Morocco. The couple then moved to the Canary Islands. But tragedy entered Sanmao’s life again.

“I was told that if her parents had not been with her when José drowned, she would have hurled herself into the sea. She was a very cheerful woman, we used to laugh a lot in her company, but at the same time she was a very tragic person,” says Carmen.

Unable to remain in Spain without her love, Sanmao returned to Taiwan, where her thousands of followers were sometimes too much for her.

“During the time I spent in the desert, I became an uncomplicated, laid-back woman who enjoys solitude. That is why the constant dinners and events that now fill my life make me feel like someone who is arriving for the first time in a wonderful place and is feeling confused and dizzy, as though under a spell,” she wrote.

Sanmao continued to publish, while keeping up a busy lecturing and traveling schedule. But despite her special relationship with Spain, she never saw her work published in Spanish.

In 1991, after being diagnosed with cancer, Sanmao committed suicide while undergoing treatment in a Taipei hospital.

“In all these years, we were only able to read a small selection of her work that Reader’s Digest translated into English and Spanish for sale in the United States and Latin America,” says Carmen Quero. “We are really excited about this.”

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.