Spanish Civil War mass grave yields preserved hearts and other organs

The organs of dozens of victims killed in 1936 on a hillside in Burgos by Franco's forces have been conserved

“In the end, your heart and mine will be shipwrecked in an ocean of bones,” wrote Miguel Hernández to his wife in 1937 from a trench during the Spanish Civil War. Almost 80 years later, the poet's prediction came true when forensic anthropologist Fernando Serrulla was called to La Pedraja in Burgos, site of one of the biggest mass graves of the conflict, where brains been found preserved inside victims' skulls, along with a heart that stopped beating in 1936.

“When I arrived at the grave, I was astounded. I have been working as a pathologist for 30 years and I have never seen anything like it,” says Serrulla, who is based at the Galician Institute of Legal Medicine.

They found 45 brains in the grave, two of which still contained the bullets that killed them

Between July and November 1936, the forces of General Francisco Franco buried 104 corpses in this mass grave. In a neighboring site, they buried 31 more. The dead were young men and women who supported the Republic Franco had set out to destroy. They were arrested in nearby villages – Briviesca, Miranda de Ebro and Santo Domingo de la Calzada. The blue shirts picked them off the streets and imprisoned them. Then, in the so-called clearances, they loaded them onto trucks, drove them to the hillside and put a bullet through their heads.

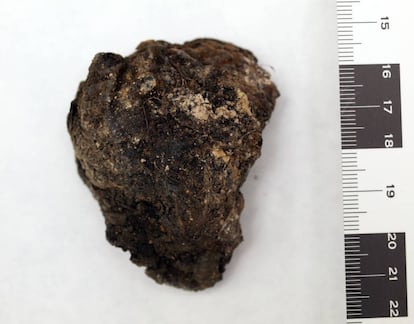

Eighty years later, 45 brains and one heart are still intact. “This is the only such case we know of,” says Francisco Etxeberria, the pathologist in charge of La Pedraja’s exhumation, an emotional operation carried out by the Aranzadi Society of Science, which has carried out more than 100 exhumations across Spain. Located on the Camino de Santiago, La Pedraja has proved the most revealing. “There are even two brains that still contain the bullet that killed them,” says Etxeberria.

The unique preservation of the brains and the heart at La Pedraja has a scientific explanation. According to Serrulla, whose findings have been published in Science and Justice magazine, the grave was dug in watertight clay soil with a high acid content and the summer of 1936 was cold and wet.

“The grave was like a swimming pool,” he says. “Most of the bodies had a bullet in the neck and the water seeped into the skull. Water does not allow the growth of the microbes that trigger decomposition. So the fatty brains were saponified and turned to soap.”

Now stored in a refrigerated chamber at the Verin Hospital in Ourense, the organs still feel greasy and are only one sixth of their original size, reduced from a kilo and a half to the equivalent of half an apple. “This is the biggest and best preserved collection of saponified brains in the world,” says Serrulla. “The executioners wanted to eliminate their victims and stamp out their enemies. But they could not get rid of their ideas, nor their brains.”

“The executioners wanted to eliminate their victims and stamp out their enemies. But they could not get rid of their ideas, nor their brains,” says Fernando Serrulla.

Rafael Martínez Moro, a public works contractor, was among those shot and buried in La Pedraja. He was killed on October 3, 1936, when he was 44. His crime was to be president of Briviesca’s Socialist Association in a town with a population of 3,500. His was one of 15 bodies that DNA evidence helped to identify, while the owner of the heart has remained anonymous.

Martínez Moro’s son, Rafael Martínez Martínez, was 14 when his father was killed; he was more than 90 years old when he stood by the grave alongside the children and siblings of the other victims and watched his body be exhumed,. “It is not fair to say you should forget they killed your father as Mariano Rajoy suggested,” said Miguel Ángel Martínez Movilla, grandson of Martínez Moro and representative of the Association of the Victims’ Relatives in Pedraja.

An architect based in Briviesca, Martínez Movilla recalls how the Aranzadi team unearthed personal items that had become mixed up with bones – gold teeth, glasses, coats and a wallet. “And then suddenly the first brain turned up,” he says. “It was intensely emotional for the relatives that were there.”

Examined under the microscope, the brains still show structures related to the nervous system. And a preliminary study suggests one suffered a subarachnoid hemorrhage – an injury that often follows a blow to the head during life. “We have never had evidence before of traumas preceding death,” says Serrulla. “This indicates the use of torture.”

Serrulla recalls that the UN rapporteur Pablo de Greiff urged Mariano Rajoy’s Government to lift the Amnesty Law of 1977 and investigate crimes carried out by Franco's forces during the Civil War. Should that ever happen, the brains found in La Pedraja could be used as evidence.

Serrulla and Etxeberria both mention the fact that while 2,200 mass graves from the Civil War have been located, only 300 have been exhumed, disinterring 7,000 victims. That is 7,000 out of 114,000 missing, a figure that puts Spain second only to Cambodia in terms of victims whose remains have never been found, according to Judges for Democracy.

While De Greiff asked the Spanish Government to make it state policy to locate and open the mass graves from the Civil War, the government of Prime Minister Rajoy abolished financial help for the families of Franco's victims. The exhumation at La Pedraja has been financed by relatives and a grant of around €150,000 from José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero’s Socialist Party administration.

But Miguel Ángel Martínez Movilla, says that the search for his grandfather and the other bodies found in La Pedraja started long before 2010. “We began to meet on this hillside in 1975,” he recalls – the year Franco died.

They knew the bodies had been buried in the vicinity, approximately 10 km from the archaeological site of Atapuerca. There, in those caves in 1975, the authorities were pouring money into exhuming human remains that were hundreds of thousands of years old. “It is curious how much was spent on Atapuerca and the scant resources invested in finding the bodies of those killed 80 years ago, whose children and siblings are still alive and who have been searching for them in the ditches,” says Martinez Movilla.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.