A passion for Fidel

Gabriel García Márquez heard the name of the Cuban leader for the first time in 1955, when he was in exile alongside a group of Latin American intellectuals

Gabriel García Márquez heard the name Fidel Castro for the first time in 1955. The Colombian writer was then in exile alongside a group of Latin American intellectuals who were all waiting for their respective countries’ dictators to fall. Thus, when the Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén opened the window of his bedroom one morning and shouted, “The man fell!”, every one of them thought it was his own man. The Paraguayans thought it was Stroessner. The Nicaraguans assumed it was Somoza, the Colombians Rojas Pinilla, the Dominicans thought of Trujillo, and so on. It turned out to be Juan Domingo Perón and a little while later, while talking it over, Guillén confessed that he did not have much hope of seeing Batista fall from power. It was then that the poet told him about a young man named Fidel who had just gotten out of the prison after assaulting the Moncada barracks.

Three years later, García Márquez was in Caracas working as a journalist and reporting on the first year of the Marcos Pérez Jiménez administration in Venezuela when the news of Castro’s victory came. Two weeks later, he and Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza boarded a plane with a group of journalists en route to Havana. García Márquez would become a member in the inner circle of the Prensa Latina News Agency founded by Jorge Ricardo Masetti and Che Guevara in the summer of 1959. Since then, Cuba and Fidel Castro who represented almost the same thing to García Márquez, became inseparable in his mind.

“The first time I saw him with those merciful eyes was during that great and uncertain year of 1959, and he was convincing an employee at the airport in Camagüey to always have a chicken in the fridge so that the American tourists would not believe that imperialist tale that said that Cubans were dying of hunger,” García Márquez recalled.

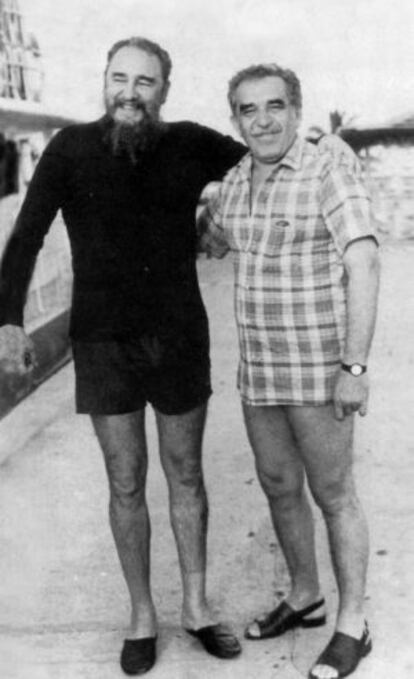

As a journalist of Prensa Latina first, and as a defender of the revolutionary cause throughout the world when he was already a famous writer, García Márquez knitted such a special friendship with the Cuban leader over the years that the former became the latter’s confessor and literary adviser, his accomplice in mediating conflicts in the region, including service as special envoy on a secret mission to the United States during the Bill Clinton administration.

When García Márquez and his wife Mercedes began to travel to Cuba more frequently, Castro put one of the most opulent Cubanacán residences in Havana at their disposal. That large house quickly became a meeting place for discussion, an activity that both of them cultivated as long as their health allowed.

Castro put one of the most opulent Cubanacán residences in Havana at García Márquez’s disposal

In one of those soirées that lasted until the sun rose over the garden table, Castro and the Colombian writer came up with an adventure - to create a film and television school for Third World students that would serve as a counterweight to “imperialist cinematography.” The Foundation of the New Latin American Cinema was founded in 1985 under the direction of the Nobel laureate and, a year later, the school opened. García Márquez gave a workshop on screenwriting that became legendary. The course was titled “How to Tell a Story.” Francis Ford Coppola, Robert Redford and Costa-Gavras are some of the filmmakers who have participated in workshops, courses, and seminars at the school.

The author of One Hundred Years of Solitude cultivated all kinds of friendships in Cuba, from filmmakers such as Julio García Espinosa to commanders like the legendary Barbarroja, Manuel Piñeiro, when he was in charge of organization and support to guerrillas and liberation movements in Latin America. But, that house was Fidel’s refuge more than anything else. He visited without calling, mostly late at night, to talk about all kinds of subjects for hours. “Sometimes he would get voraciously hungry and once he ate 28 scoops of ice cream,” the writer used to say.

His privileged relationships allowed him to mediate with Castro for many different things, from letting the writer Norberto Fuentes - a friend to Tony La Guardia and Arnaldo Ochoa, both officials who were shot in 1989 - off the island, to obtaining an interview with Fidel for a journalist friend.

During the Fourth Ibero-American Summit in Cartagena de Indias in 1994 Gabo rode by his friend in a horse-drawn carriage through the streets despite the fact that the Cuban leader had received death threats. Four years later, Castro invited García Márquez to sit next to him during the mass that Pope John Paul II gave in Plaza de la Revolución before one million Cubans.

Castro would get voraciously hungry and once he ate 28 scoops of ice cream”

García Márquez also handled discreet maneuvers with Clinton during the boat people crisis. He dined with the former American president at the home of the writer William Styron at Martha’s Vineyard in the summer of 1994. In the 1997 bomb attacks against Havana hotels, he served as a messenger between Castro and Clinton, allowing the two countries to establish secret exchanges to cooperate on anti-terror policies for a while.

In his Havana home, García Márquez had a piece painted and given to him by Tony La Guardia. The gift was displayed alongside the works of great Cuban painters like Víctor Manuel o Amelia Peláez. The Colombian Nobel Prize winner, who had been a friend to La Guardia, did not remove the oil painting from the wall after his execution for treason.

Gabo had privileges in Cuba. He was critical in public and in private of bureaucracy and of many things in Cuba’s style of socialism. Still, he was always loyal to his friend Fidel since the day he saw him convincing that waiter in the Camagüey airport.

Translation: Dyane Jean François

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.