A web of spies

A new book reveals how Germany and the Allies sought to manipulate neutral Spain during WWI

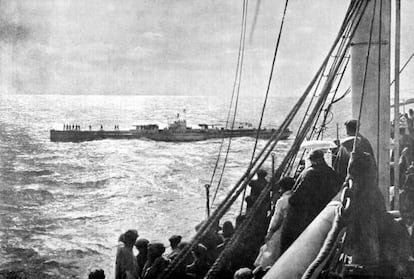

Spain managed to avoid taking sides in the First World War, but its neutrality was heavily comprised. The Spanish government was infiltrated by spies from all the major nations involved in the conflict, who on occasion managed to influence important decisions; the main newspapers accepted bribes to publish German or Allied propaganda; meanwhile, big business made a fortune selling raw materials to all contending parties, fuelling an unprecedented export boom. The Spanish coast was the scene of a vicious submarine war that didn’t respect neutrality: by the end of the conflict, German U-boats had sunk more than 12.5 million tons of cargo from merchant ships, among them many Spanish vessels. And while the population suffered the effects of reduced imports and shortages of basic foodstuffs, black marketers made a fortune.

King Alfonso XIII, whose situation since ascending the throne in 1902 had been precarious (he would be forced to abdicate in 1931 following the collapse of a military regime installed in 1923), saw himself as a possible peace mediator, while at the same time fearing he would be overthrown at any moment. “The regime was thinking only of itself, and wondering if it would still exist tomorrow,” says Fernando García Sanz, who has just published España en la Gran Guerra (or, Spain in the Great War) after more than a decade of research. “No other neighboring country would have tolerated so many violations of state sovereignty. Nobody in a position of authority was up to the task. And Alfonso XIII, who was nobody’s fool, understood that there was an emerging middle class that was determined to take its place in society and that the war could accelerate that process. The king wasn’t interested in the fact that his country had been overrun by spies, simply that one of them could assassinate him.”

From a historian’s perspective, the fact that Spain was swarming with spies working for all the great powers has proved a goldmine, and García Sanz has been able to access the archives of Germany, Great Britain, France, the United States and Russia. “The Spanish didn’t realize that all their codes had been broken even before the war started. All communications were intercepted, including those of Alfonso XIII,” says García Sanz.

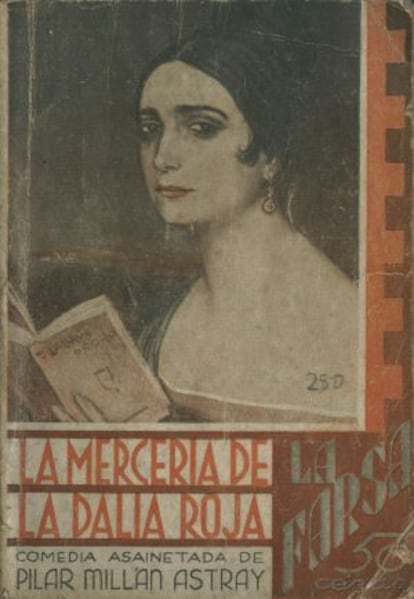

Among the cast of characters in his book are novelist and German collaborator Pilar Millán Astray, sister of José Millán Astray, the founder of the Spanish Legion. “Mata Hari [who spent time in Madrid during the war] was a rank amateur alongside many women who became spies: some of them were so skilled that we can still only suspect what they got up to,” says García Sanz. Pilar Millán Astray, a widow bringing up three children on a low income, offered her services to the German embassy in Barcelona. After striking up a friendship with Sir Arthur Henry Hardinge, she was able to monitor his movements and enter his room in the Hotel Colón and copy secret documents, says García Sanz, who paints a picture of a country where everybody – barmen, chambermaids, policemen and even politicians – had their price, or could either be blackmailed, or were prepared to spy out of sympathy for one side or the other.

The Spanish didn’t realize that all their codes had been broken before the war started”

But there was one institution that proved incorruptible, says García Sanz: the Civil Guard: “This was a corps that could not be swayed, driven as it was by an iron discipline.” As one French agent noted in his diary: “Following orders, today they’ll go after the Socialists, and tomorrow, again, following orders, and with the same conviction, against the reactionaries.”

In the run-up to the war in the month following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, little thought was given to Spain, as much as anything because few people thought the conflict would last as long as it did. “Neutral countries were very important for the war effort. Spain quickly became vital. It was impossible for it to stay out of the conflict completely. We had important raw materials and were strategically located,” says García Sanz.

He believes that the Allies missed an important opportunity to win Spain over to their cause; whereas the Germans took a much more proactive approach, and made overtures to the government from the very start of the conflict. Its arguments were simple and effective: France and Great Britain had long been Spain’s enemies, while Italy’s siding with the Allies was against the pope’s wishes. “This was an efficient message, a visceral one. The Allies talked about freedom and democracy, which was not an easy sell in Spain to the government of the day.”

In the end, Alfonso XIII was never called on to mediate a peace between the warring sides, and despite Spain’s important behind-the-scenes role, it was forgotten as soon as the armistice was signed in November 1918. It would remain largely overlooked and excluded by the great powers for the rest of the 20th century.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.