The other Spanish Civil War

New book charts the propaganda battlefront between Republicans and Nationalists

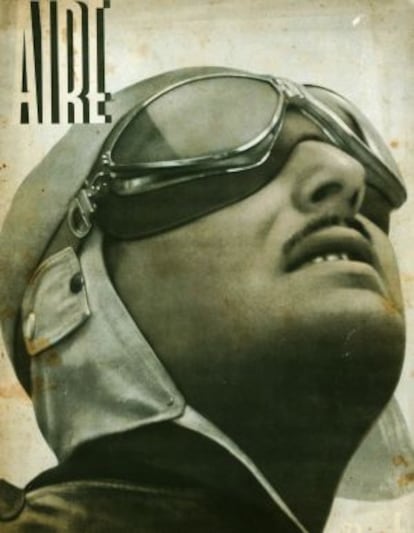

There was a parallel war taking place in Spain between 1936 and 1939. It was conducted by both Republicans and Nationalists, using photographs, drawings, publications and posters that sought to portray their view of the conflict to Spaniards and the wider world.

Around 20,000 works about the Civil War have been published since the conflict ended. Some of them were written during the four-decade dictatorship that ensued, and their goal was to praise Francisco Franco while humiliating the defeated side. The latter, in the meantime, tried to convey their version of events, often in a less than successful fashion, at least within Spain's borders. The international propaganda war, however, would be ultimately won by the Republicans.

Paul Preston, a well-known expert on Spanish history who wrote the foreword to Guerra gráfica España 1936- 1939 (or, Graphic war, Spain 1936-1939), considers that this new book on the topic is justified. "The illustrations show a new generation born out of a Civil War that triggered passion, cruelty and heroism," says Preston, who has written extensively on the Spanish conflict.

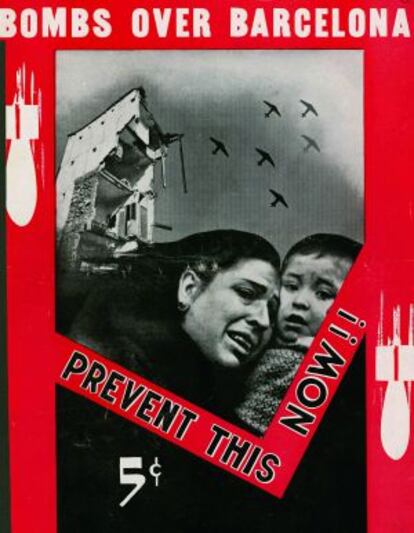

In the book, the journalist and writer Michel Lefebvre-Peña holds that while the Republicans may have lost the war itself, they won when it came to offering the world their own vision of a ravaged Spain. Guerra gráfica. España 1936- 1939 includes work by Spanish poets, painters, writers and photographers including Agustí Centelles, Alfonso Sánchez Portela and José María Díaz Casariego, but also by foreign correspondents such as Robert Capa, Gerda Taro and David Seymour Chim, who used their cameras to document the fervor of a people up in arms, and whose images lie somewhere between photojournalism and propaganda. Some of these shots have been reproduced countless times and transformed into icons of the Spanish Civil War: Capa's The Falling Soldier or his brigadier with his fist in the air come to mind.

Lefebvre-Peña, the son of a Republican military officer who went into exile in France, began gathering material at Paris' famous flea market Marché des Puces, where he found a packet of photographs published by Paris-Soir. "Buying those images was both surprising and upsetting. I later left them behind in a taxi in Brussels and years later came across them, little by little, in London, Paris, Buenos Aires and to a lesser extent in Spain. In them you can see André Malraux with his squadron," he recalls. "I managed to find the archives of a brigadier, of the Spanish ambassador to Brussels, Ángel Ossorio; photo albums from nameless Francoists, Republicans and Germans; postcards, posters, and above all, magazines."

The book focuses on Franco's enemies, or at least those who confronted his regime on the propaganda front. Chief among these are Willi Münzenberg, propaganda chief for the Comintern (the Communist International), who fled Berlin in 1933; Jaume Miravitles, propaganda commissioner for the government of Catalonia, and Robert Capa.

There are two photographic visions of the Civil War: one provided by the foreigners -- all the world's press agencies sent correspondents to the Spanish front from the onset of the war -- and one provided by Franco's Nationalists. "The photographs do not show the war, but rather the image of the war that the photographer, the censor or the newspaper wanted to convey, and the interests of these three agents could be either contradictory or convergent," notes Lefebvre-Peña, who spent 10 years of his life building up this archive.

Some of the 600 documents in the book include never-before published shots by the photographers Walter Reuter, Ione Robinson and James Abbe; posters by Josep Renau; anarchist magazines, and brochures by the Dutch photographer Cas Oorthuys.

The image war between the Francoists and the Republicans was constant from the start. While the former quickly distributed pictures of churches being burnt down, the latter scrambled to plaster walls with posters denouncing the fascist cruelty and its links to German Nazism.

The Franco side was efficient in its response to Republican propaganda. In London, Paris and New York, magazines were printed using the same techniques as their adversaries to depict the horrors of war. In the brochure Notre but: sauver une civilisation (Our goal: Saving a Civilization), Franco claimed his uprising "isn't a military coup in the old style, nor a self-interested class movement; the authentic Spain has risen up to save its personality as a nation."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.